the home front in World War II

Figure 1. Saucepans were collected for aluminum for making aircraft after a British Government appeal in 1940.

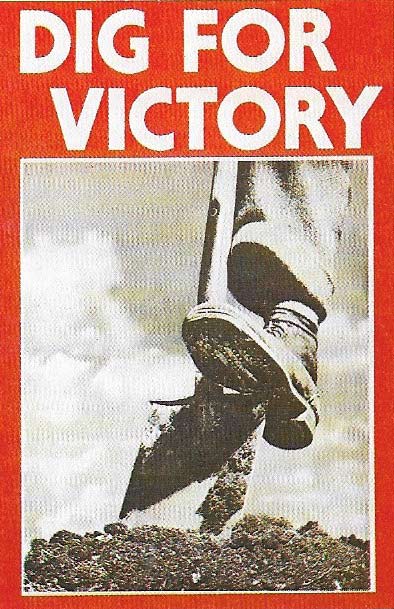

Figure 2. "Dig for Victory" was an early wartime slogan thought up to promote the campaign for home-grown food.

Figure 3. Refugees flooded onto the roads of Europe as the German armies advanced. This Frenchman's horsedrawn vehicle laden with goods was one way of overcoming the petrol shortage; bicycle taxis were also common.

Figure 4. Nazi military bands like this one, photographed in the Place de l'Opera in Paris in June 1941, often played in public in the occupied countries. Ostensibly a goodwill gesture, they were also a symbol of German strength.

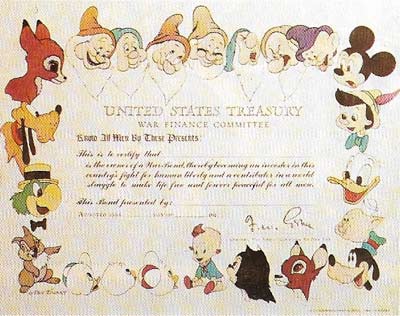

Figure 5. War savings were encouraged by all countries to stop inflation, this US Victory Bond was designed by Walt Disney.

Figure 6. The mobilization of women was greatest in the USSR. Here ammunition is stacked to repel the Leningrad siege.

Figure 7. The destruction of Hiroshima on the morning of 6 August 1945 was the horrific culmination of the war in the Pacific.

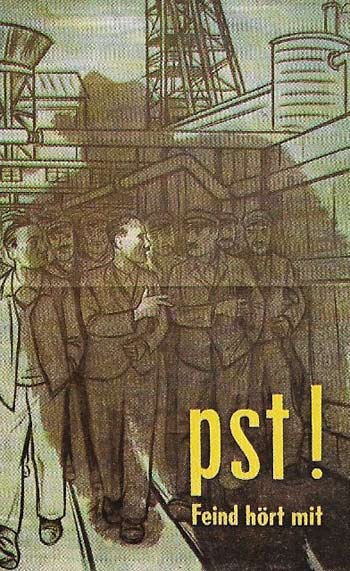

Figure 8. Propaganda was used by both sides, both offensively and defensively. This German poster warns against careless talk.

Figure 9. Allied bombing devastated the non-military city of Dresden. These are the ruins of the church of St Sophia.

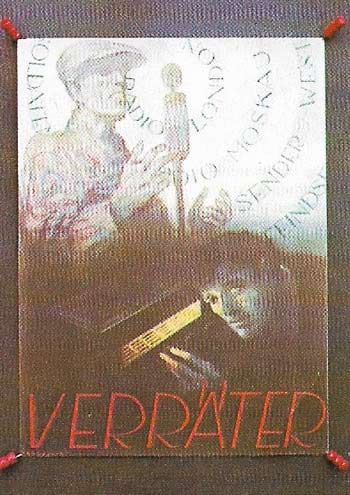

Fig 10. "Traitor" warns this German poster. German propaganda techniques were generally more sophisticated than the Allies'.

Fig 11. Evacuation was carried out by the British government at the beginning of the war because of the fear of massive air raids. Nearly 1,300,000 people mainly children left the cities.

World War II has often, and accurately, been described as "The People's War". No previous conflict in history had so directly involved the civilian population of the combatant countries or caused them so much privation and death.

Civilian involvement in war

Even before war had been declared civilians had become involved through conscription, introduced in Germany in 1934, in Great Britain in June 1939, and in the United States on a selective "unlucky dip" basis in 1940. Once the war began even those civilians who escaped being called up into the armed forces found themselves in varying degrees directed into home defense (Local Defence Volunteers, later – the Home Guard) or civil defense or into essential work in factories (Figure 6) and vital services such as transport. In every combatant country (except the United States, which could meet almost all the demands made upon it) the share of the national resources allocated to civilians was by the end of the war sharply reduced to give priority to the fighting men.

|

| Britain's Local Defence Volunteers we're formed in May 1940. Here two railwaymen are briefed. |

Although they vastly outnumbered the soldiers, the civilians were in far less danger. Even in Germany casualties among civilians, including those caught up in military operations, were estimated at no more than 700,000 compared with 3,500,000 servicemen who died. The figures for Britain were 62,000 against 326,000 and for Japan 260,000 civilians compared with 1,200,000 servicemen; the United States had virtually no civilian casualties. But the civilian's life was far more at risk than in any previous wair Although each country claimed at first to be directing its bombers against only military objectives, such restraints were soon abandoned (Figure 9). But bombs were not the main cause of civilian deaths. Under German occupation, far more deaths were caused by disease, famine and mass murder.

Civilian daily life

Even within occupied Europe daily life varied enormously between different countries. In Denmark, Hitler's "model protectorate", the standard of living was far higher than in Britain. In France, if one had access to the black market, it was also possible to live reasonably well. But in Holland by the winter of 1944–1945 people were living on tulip bulbs and in the Channel Islands only the arrival of Red Cross parcels prevented starvation. All the occupied countries shared some shortages and discomforts. Fuel, both for heating and transport, was scarce (Figure 3). Everyone's life was encompassed by curfews, permits, and the fear of being rounded up as a suspect or forced-labor "volunteer".

|

| Air raids on London – the blitz – began on 7 September, 1940 and lasted until mid-1941. In the opening phase the Capitol was bombed on 57 consecutive nights. In the first four months 13,339 people were killed and 17,937 injured. |

In the countries still under arms the civilian population was encouraged to believe that a vast gulf separated them from their counterparts in enemy lands. Civilian experience in Germany probably had more in common with life in wartime Britain than in any other country. Both suffered the upheaval of evacuation (Figure 11) and of long nights in shelters.

Almost all necessities were either rationed or hard to find and although the German system of control was more complicated and less efficient than the British there were many similarities between them. Household textiles and clothes, for example, were rationed on a points system in Germany in 1940 and in 1941 the same system was used in Britain. To find consumer goods of any kind, from babies' prams to furniture, necessitated a long search and in both countries as coal was diverted to the war factories people struggled in winter to keep warm.

Food rationing made the deepest impact on most people and here, as in other spheres, the Germans probably suffered most. The same basic items were rationed in both countries: meat, butter, fats, bacon, cheese, sugar, jam, milk. and eggs. But in Germany one also had to part with coupons for bread and potatoes, both plentiful in Britain (Fig 2), and there were no "lend lease" supplies from America to help fill empty stomachs.

American soldiers arriving in Europe readily admitted that "back home they don't know there's a war on". Even in the United States there was, in theory, some rationing – of many canned goods, sugar and coffee – but in practice there was no real shortage of any type of goods. The Japanese fuel shortage prevented their indulging in the constant ritual bathing demanded by tradition. Japan also suffered a near-breakdown in the railway and island-ferry transport systems, and by 1945 food supplies had shrunk to no more than 1,300 calories a day, less than half the normal minimum.

A new prosperity

If the war years brought unprecedented hardship to civilians they also brought many benefits. In both Germany and Britain, due to the fairer sharing out of food supplies and full employment, poorer families lived better than they had ever done before. Everywhere, rigid price controls kept the rise in prices within limits; by 1945 the cost of living was only a third higher than before the war.

For factory worker and farmer alike, in every combatant country, these were boom years. The new prosperity masked deeper long-term changes. The drift from country to city was accelerated; there was increased pressure for urban amenities to be extended to the countryside; it was demonstrated that full employment was not an impossible dream and everywhere people demanded a fairer social order after the war.