Toscanelli, Paolo dal Pozzo (1397–1482)

Toscanelli absorbed in his calculations for establishing the extent of the Atlantic Ocean.

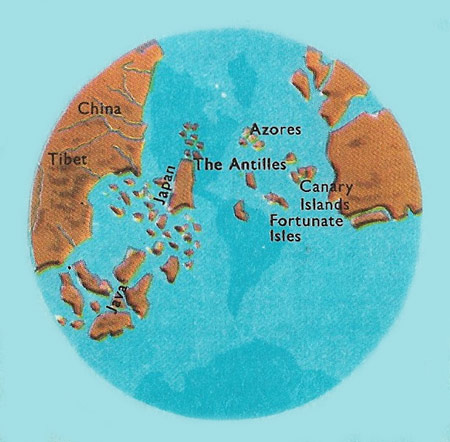

How the Western Hemisphere looked according to Toscanelli. Its true outline is shown in blue.

It is often said that the idea of the Earth being round originated in the fifteenth century at the time of the discovery of America; this geographical conception, however, goes back to some centuries before Christ. Eratosthenes (in the 3rd century BC) and Ptolemy (2nd century AD), the two greatest geographers of ancient times, clearly demonstrated in their various works that they were convinced of the Earth's roundness. The natural question ten to ask is: "How is it then that at the time of Christopher Columbus many geographers were not at all convinced of this?" This can be explained by the fact that when the so-called 'Barbarians' invaded Europe they destroyed most of the ancient manuscripts they came across; those that were saved were kept for hundreds of years in the libraries of monasteries. So, in time, mankind forgot much of the vital knowledge which learned men of the past had expounded.

So much, in fact, had been forgotten that the geographers of the Middle Ages made the strangest conjectures about the earth's shape; the great majority of them believed that it was a flat disc surrounded by an immense ocean. The first man seriously to examine this question again was the Florentine mathematician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, who based his theories on the manuscripts of the ancient geographers.

Firmly convinced of the Earth's roundness, and after having pondered at great length on Ptolomey's work in particular, Toscanelli believed that it would be possible to accomplish a feat never before attempted by man: this was to reach the countries of the East (that is the coasts of Japan and China) by navigating always westward through the Atlantic Ocean. No one until then had ever thought of such a possibility, it being a common belief that the immense Atlantic Ocean, full of horrible monsters, would eventually lead one into infinity! It was thought that the only possible way to reach the East by sea was by travelling around the coast of Africa and then bearing east. But Toscanelli, even though convinced of the truth of his theory, was faced by a very difficult problem – how extensive, in fact, was the Atlantic? For no one would venture into that immense and unknown waste of water without knowing with some degree of certainty what distance separated him from his goal.

Toscanelli therefore realized that in order to find the true answer to this problem he needed to know with absolute exactness the following data: the size of the earth and the extent of Europe and Asia. Since it was then not known that other lands existed besides Europe, Asia and Africa, he felt certain that once he had ascertained these facts he could, by a not to difficult calculation, arrive at the extent of the Atlantic Ocean. After much study Toscanelli, who was a skilful mathematician, concluded that he could give precise data. The result from his calculations was that the distance between Lisbon and China was a much shorter voyage than some Portuguese navigators were considering undertaking in circumnavigating Africa. In 1474 Toscanelli designed a geographical chart in which he indicated the precise route for the voyage. In the same year he sent the chart to Canon Ferdinand Martines of Lisbon so that it could be brought to the notice of the king of Portugal, Alphonso V. In the letter accompanying the chart Toscanelli pointed out the advantages of the new route. 'I give you material proof,' he wrote, 'of a navigational route shorter than that which you take to Guinea. On my chart are clearly drawn your shores from which you will have to start navigating, always bearing West and the shores at which you should arrive; also how many sea miles you should travel from the city of Lisbon to the most noble and great city of Quinsay.' But Alphonso V considered the voyage to be extremely dangerous and took no notice of the Florentine geographer's letter or chart.

Only twenty years later someone attempted the journey outlined by Toscanelli: and that bold man who, having learned of Toscanelli's letter and chart, did everything to put the theory into practice was Christopher Columbus.

Toscanelli's calculations

Actually, Toscanelli's calculations were not very accurate and his results were far too low. His mistake was caused by his having believed that the Asia continent was greater that it really is; in his calculations this reduced the sea distance between the coast and the Iberian peninsula and that of Asia. One can well believe that had Christopher Columbus known the real distance between Portugal and China he would certainly not have undertaken such an adventurous voyage which, with ships of that time, would have seemed completely out of the question, particularly as he was unaware of the existence of an intervening continent.

It was due, therefore, to the miscalculations of Paul Toscanelli the Christopher Columbus undertook such a great and perilous venture – a voyage that achieved for him nothing less than the discovery of a new continent, America.