Africa in the 19th century

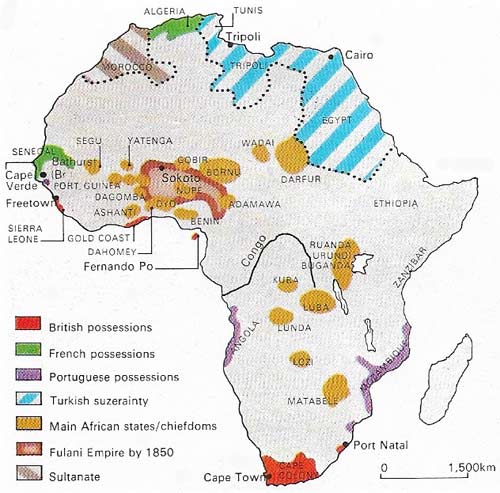

Figure 1. European possessions in Africa in 1830 were few. France had invaded Algeria (1830) and some Boer (Dutch) settlers were trekking out of the British Cape Colony into the hinterland of South Africa. Britain and France has a few tiny colonies in West Africa – Senegal, Sierra Leone and a Gold Coast. Apart from Europeans on trading posts, only the Portuguese had old-established colonies – in coastal parts of Angola and up the Zambezi valley of Mozambique. Although the Egyptians had conquered the Nilotic Sudan in 1821, the rest of the continent consisted of African empires, kingdoms, and peoples who still maintained their independence.

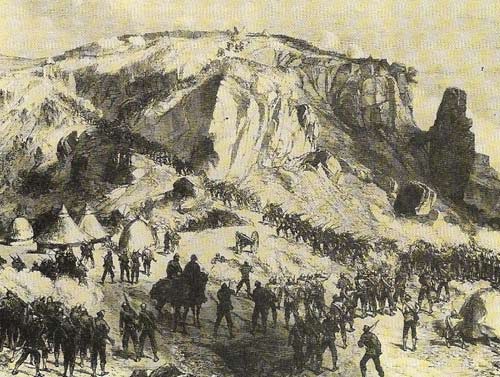

Figure 2. The storming of Magdala, a mountain citadel in Ethiopia by British forces in 1868 was one of the most extravagant episodes in the history of relations between Europeans and Africans in the 19th century. An expedition under General Napier invaded Ethiopia to punish its emperor, Theodore (or Tewodoros) for briefly holding prisoner a British consul and some Europeans. After Magdala fell, the emperor dramatically committed suicide and the expedition then withdrew.

Figure 3. This Ethiopian village had hardly changed at all since the last century. Then, as a community of peasant cultivators producing little more than what was necessary for subsistence, it would have been typical of rural Africa.

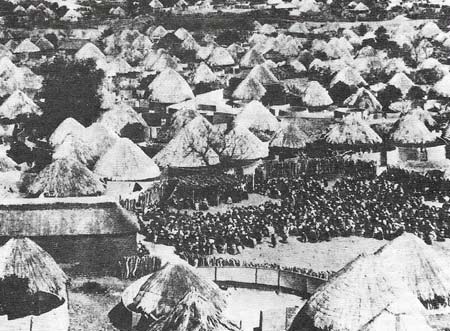

Figure 4. Mochudi in Botswana was one of several towns to Devon long before the coming of Europeans – notably in the Sudanic belt, Yorubaland in West Africa, Botswana and southern Africa.

Figure 5. Johannesburg in South Africa grew from a farm on the veld to a sprawling city by 1900. The discovery of gold in the Boer Republic of the Transvaal in the mid-1880s led to rapid development.

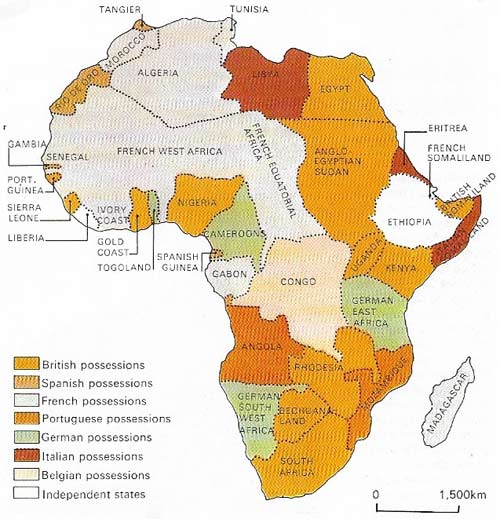

Figure 6. A map of Africa in 1914 shows how it had become partitioned among seven European countries. This partition was a rapid process taking place during the last 20 years of the 19th century. Only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent of European rule. Although some territories were termed protectorates (like Uganda and Morocco) rather than colonies, Europeans were firmly in control. The four white-ruled colonies in South Africa had formed a union in 1910 but remained a British dominion. Colonial boundaries drawn up entirely by Europeans were often merely straight lines on the map. This causes great problems when Africa regained independence.

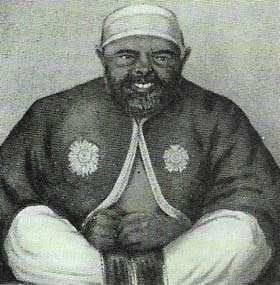

Figure 7. Moshweshwe (c. 1786–1870) was the founder of the Sotho nation (Lesotho) in Southern Africa, and an example of how African rulers adopted practices and ideas introduced by Europeans. Moshweshwe emerged as leader of the Sotho, a small group of people who found refuge in the Drakensberg Mountains from the devastation produced in the interior of Southern Africa by the Zulu and other warrior kingdoms on the 1820s. He was a man of peace, and ensured the protection of his people through wise diplomacy. Lesotho rapidly increased in prosperity, making use of European techniques. It was a British protectorate from 1868 until its independence in 1966.

The 19th century was a period of great and often rapid change for much of Africa, set in motion either by Africans themselves or by outsiders, especially Europeans. The partition of almost the whole continent among seven European states took place in the last 20 years of the century. The previous 80 years saw largely a continuation of trends already long established. Tiny trading "factories" (or castles) set up by European slave traders dotted the west coast of Africa, from Cape Verde to the Congo estuary (Figure 1). On the southern tip of the continent, Britain had taken over the settlement of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape.

Foretaste of expansionism

The extension of European influence was gradual: in 1820–1822 Egypt, technically an Ottoman dependency, conquered the Nilotic Sudan; in 1830 the French invaded the Ottoman dependency of Algiers and began the long, costly process of conquering it; and in the late 1830s Dutch farmers known as Boers trekked deep into the interior of southern Africa, away from British control.

With the abolition of the slave trade by most European countries late in the 1800s, trade in palm oil and other tropical products largely replaced it in West Africa. Only the French on the River Senegal expanded fairly deep into the interior; but missionaries were active, especially in areas settled by freed slaves, such as Sierra Leone.

|

| Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, was typical of European coastal towns in tropical West Africa. It was built in colonial style with churches, business centers and separate areas for whites and blacks. |

Islam had so long penetrated what is known as the Sudanic belt of Africa that by the beginning of the 19th century it was thoroughly "Africanized". Much of this region was swept, from the 18th century on, by a wave of religious revival, spearheaded by holy wars, jihad, waged against black Muslims as much as against pagans. A jihad in 1804 rapidly conquered all the old Hausa city states (such as Kano) and beyond and led to the establishment of a huge new empire, the Sokoto caliphate, which survived until taken over by the British in northern Nigeria in 1903. Other Muslim empires were created on the middle Niger and in what is now Guinea and the Ivory Coast, where prolonged opposition was encountered by French invaders in the 1880s. South of the Sudanic belt, several great kingdoms, such as Ashanti and Dahomey, continued to expand and prosper (and offered vigorous resistance to the British and French respectively), while others began to disintegrate.

Rise of Ethiopia and the Zulus

In Ethiopia, the ancient Christian Amhara Empire, after a period of prolonged feebleness, slowly and painfully recovered during the reigns of three forceful emperors – Theodore (reigned 1855–1868), Johannes IV (reigned 1868–1889) and Menelik (reigned 1889–1911). These rulers asserted their power against that of the mighty landed aristocracy and the Coptic Church. Menelik not only maintained his position against , the powerful northern barons and greatly expanded the boundaries of Ethiopia in the south, but beat off an Italian attempt to conquer his state, at the Battle of Adowa (1896).

|

| Emperor Menelik (1844-1913) successfully maintained the independence of Ethiopia against European encroachment. In 1896 his forces defeated an Italian invasion at the Battle of Adowa. |

In 1818 in southern Africa, Shaka (c. 1787–1828) became king of a small group, known as the Zulu and, by revolutionizing the military and social structure of his people, fashioned a formidable and ruthless military state which rapidly conquered surrounding people. Offshoots of the Zulu, and other groups who copied their techniques, ram-paged over much of southern and central Africa in mass population movements and tribal regroupings, known as the mfecane, the Time of Troubles.

Explorers and imperialists

During the middle years of the 19th century Africa was gradually becoming better known to Europeans through the efforts of many courageous travellers, such as the German scientist Heinrich Barth (1821–1865), in the Sudanic regions, and the Scotsman David Livingstone (1813–1873), whose travels were partly motivated by his concern over the ravages of the Arab slave trade in central and east Africa. The Welsh-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904) was more concerned with exploitation. In 1877 he completed an epic journey down the River Congo – and then sold his services to King Leopold II of the Belgians (1835–1909).

|

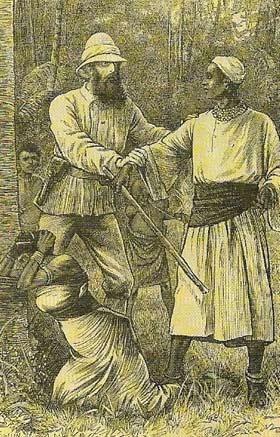

| An idealized view of European influence in this picture of the British explorer John Speke (1827–1864) with King Mutesa of a Buganda. Men like Speke, who found the source of the Nile in 1858, played an essential role in opening up Africa to Europeans. Two Scottish explorers were James Bruce (1730–1794) who went to Ethiopia and the Sudan, and Mungo Park (1771–1806) in West Africa early in the 19th century. Heinrich Barth in northern and Western Africa, David Livingstone in central and Eastern Africa and H. M. Stanley, who found Livingstone in 1872 and journeyed down the Congo, were dominant in the middle of the century. |

By this time bitter trading rivalries had grown up between Britain and France in West Africa, stimulated by British occupation of Egypt in 1882. Motivated largely by politics, a rush for African colonies began with Britain and France in the forefront, followed by Belgium and Germany, and with Portugal, Spain and Italy bringing up the rear. In many areas the conquest of Africa met with intense opposition and vicious wars of "pacification" were mounted. But resistance (Figure 2) was seldom more than local, and could be dealt with piecemeal.

In southern and central Africa the main impetus for British expansion was provided by Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902), who, from a base in the Cape Colony, appropriated a vast private empire for himself (as did King Leopold in the Congo/Zaire). The two independent Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State were annexed in a war that fully extended the power of the British Army (the Anglo-Boer War, 1899–1902). By the turn of the century the whole of Africa, except for Ethiopia and Liberia, had been conquered by Europeans (Figure 6).