Age of Discovery

Figure 1. Prince Henry of Portugal, "the Navigator", was the most important of the precursors of the age of exploration. Placing gentlemen of his own household in command of his ships. Henry developed a systematic if intermittent program of exploration beyond Cape Bojeador. By the time of his death his ships had advanced south by 2,415 kilometers (1,500 miles).

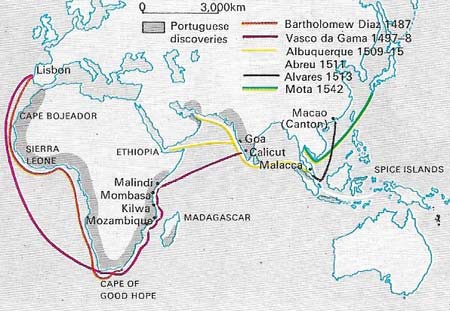

Figure 2. Vasco da Gama's voyage by which he reached Calicut in 1498 was an event of great significance, but his achievement cannot be ranked with that of Magellan or Columbus. In sailing east he completed what others had begun – Diaz had rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 and in fact accompanied da Gama part of the way on his Indian voyage.

Figure 3. Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese employed by the King of Spain, embarked in 1519 from Seville on the voyage in which he sailed through the strait that bears his name. He then crossed the Pacific to the Philippines where he was killed. Del Canó completed the circumnavigation.

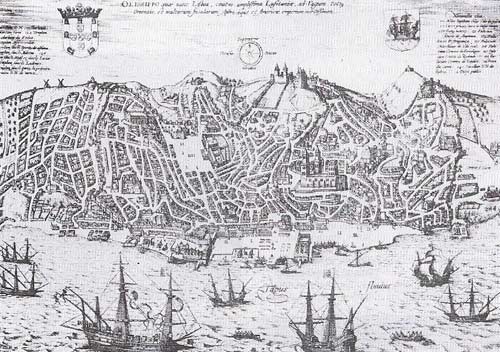

Figure 4. Lisbon in the late 16th century, with a population of about 100,000 was the largest city in Portugal. It was the nerve center of her seaborne empire where the spices of Asia were redistributed to the Mediterranean and Atlantic world in exchange for their goods. In the next century Portugal was to lose her commercial dominance in Asia and her political independence in Europe.

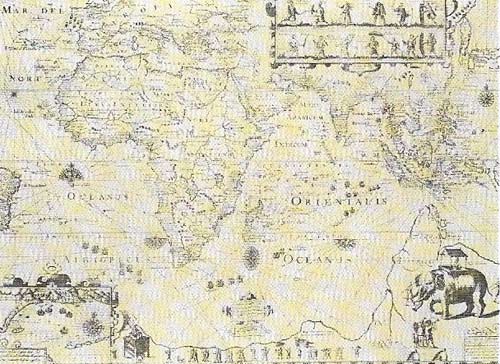

Figure 5. The route to the Indies took the Portuguese 50 years to develop from the time that Diaz rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. The greatest single step was da Gama's crossing of the Indian Ocean, but it was the later venturers who gained for Portugal her central position in the trade of the Far East.

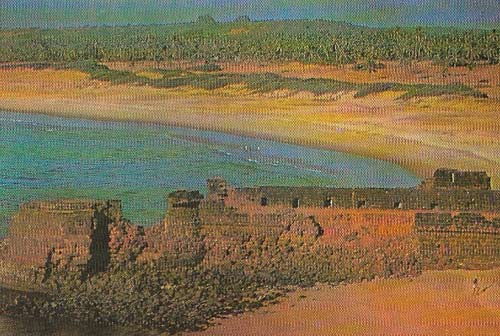

Figure 6. The Portuguese empire in the East consisted of a string of fortified trading posts all the way from Sofala in east Africa to Macao in the China Sea. The headquarters of the Estado da India was Goa on the western coast of India. The grand forts, such as this one, that the Portuguese built on Goa were meant to overawe rivals from the sea and to dissuade attack from the hinterland.

Figure 7. The Dutch began to sail eastward in 1595. Their innovation on getting to the East Indies was to leave India on their flank and sail direct from the Cape to the Sunda Strait and then to turn north to Java. This new route has the advantage of bypassing Goa and Malacca, but it also meant that they had to carry bullion or European goods direct to Indonesia, without the support of local Asian trade.

The late 15th and early 16th centuries make up one of the most momentous periods in the history of Europe and is often referred to as the Age of Discovery or the Age of Exploration. In 1492 Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) sailed west across the Sea of Darkness and discovered the Americas. In 1497 Vasco da Gama (c. 1496–1525) embarked from Lisbon, sailed down the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope, up to Mozambique and Mombasa, and then across to Calicut in India. In 1519 Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480–1521) (Figure 3), seeking the route to the Orient that Columbus had failed to find, led a Spanish expedition around the southern extremity of South America and across the Pacific to the East Indies. Magellan himself was killed, but the survivors of his expedition, returning by way of the Cape of Good Hope, circumnavigated the globe for the first time.

|

| The astrolabe, together with the quadrant, was one of the chief navigational aids that made exploration possible. |

The voyage of the Portuguese

Vasco da Gama's expedition (Figure 2) eastward was less a voyage of discovery and more an armed embassy determined to open up Portuguese commerce with the East. It was the culmination of almost a century of tentative, hesitant exploration by the Portuguese in which their frail caravels (light Mediterranean sailing ships) had groped their way along the West African coast and finally rounded the Cape. Lured by the gold and ivory of Africa, and by the prize of Eastern trade which awaited Europeans who could reach India by sea, the captains of Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) (Figure 1) paved the way for da Gama by voyages to Madeira (1418) and the Azores (1431); by rounding Cape Bojeador (1434); the discovery of the mouth of the Senegal (1444); the sighting of Sierra Leone (1460), and eventually the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope by Bartholomew Diaz (c. 1450–1500) in 1487.

The motives of the explorers

The motives behind these early explorations, whether Portuguese or Spanish, were a combination of acquisitiveness and religious zeal. Barred by the Italians from the large prize of Mediterranean trade, deprived of the profits of the luxury commerce in Eastern goods which Muslims and Venetians together controlled, the Iberians sought new routes to the sources of supply. At the same time they were spurred on by their crusading zeal.

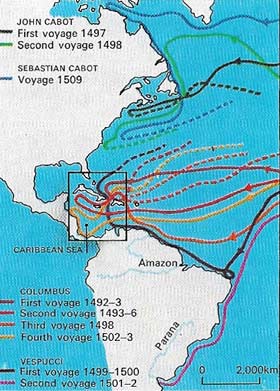

But not all the voyages during this period were by Iberians. Under Spanish patronage the Genoan Christopher Columbus sailed in search of a westward sea route to the Indies trade, and in October 1492 landed in the Bahamas, believing them to be an Asiatic archipelago. By 1504 he had made three more voyages to the Caribbean, but had come no nearer to proving that Asia had been found. Meanwhile, from England, the voyages of John Cabot (c. 1450–c. 1500) along the northeast coast of America, and the explorations of the Florentine Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512) along the north coast of South America and Brazil on behalf of the Spanish, led to the belief that there was an uncharted land mass to the west between Europe and Asia, a New World.

|

| Westward voyages, until Magellan's circumnavigation, we're a gradual process of realization that an uncharted continent lay between Europe and the Indies. While the Portuguese sailed eastward to the spice trade, Spain and England were anxious to find a quicker, westward route. |

The Portuguese had many advantages over other European rivals in the exploration of Africa and Asia. The Italians were bottled up in the Mediterranean; the Spanish were not united into one kingdom until 1479 (the expulsion of the Moors was not complete until 1492). By then the Portuguese had taken the lead.

A small seafaring nation, Portugal possessed a large fleet of ships, a seafaring population trained on ocean fishing, a well-organized system of marine insurance and investment and a royal family ready to back these maritime enterprises. Moreover, in the fifteenth century the design of European ships had developed rapidly and so had the necessary navigational aids.

Portuguese dominance in the spice trade

By finding a direct route to India by sea the Portuguese were able to gain an advantage in the spice trade. The architect of Portuguese supremacy in the Orient was Alfonso d'Albuquerque (1453–1515). In 1510 he seized the island of Goa; in 1511, Malacca. From the East Indies Portuguese ships went to China and sailed annually between China and Japan. Their twin commercial aims were to monopolize the spice trade with Europe and to get as large a share as possible of the inter-port trade of the Indian Ocean.

But in fact the Portuguese commercial empire of the sixteenth century – the result of the age of exploration – achieved less than its architects had hoped. The Portuguese succeeded in overawing but not in controlling their Asian competitors at sea. Until the coming of the Dutch they retained a monopoly of the sea route around the Cape which they had pioneered. But they never achieved a monopoly of the spice trade between Europe and Asia. The Venetians, supplied by the old land routes, continued to sell some spices in Europe, while the Portuguese did not achieve control of all the spice islands. Their Estado da India (Figure 6), a set of fortified trading-posts clinging sometimes precariously to the coast or to islands, never penetrated and certainly did not dare to challenge the empires of mainland Asia.

The explorations in the East were initially more important to Europe than for the countries explored. They indicate a shift in the center of gravity of European trade from the Italian states to the Atlantic. The new routes to the East by sea permanently changed the mercantile map of the world.