Cabot, John and Sebastian

Sebastian Cabot (from a 19th century engraving).

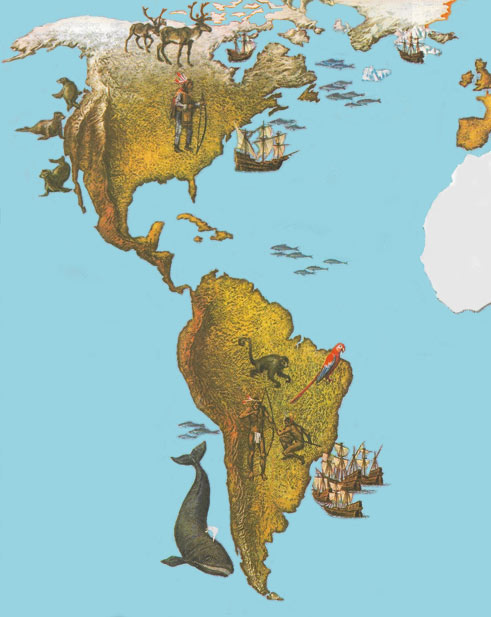

The areas explored by the Cabots shown by the location of the ships.

The English were not particularly prominent in the 'Age of Discovery'. Christopher Columbus was Genoese and sailed in Spanish ships. Ferdinand Magellan was a Spaniard, financed by his government. However, there were two great explorers, who, even if they were not Englishmen, at least sailed under English patronage and whose discoveries and achievements were made on behalf of the English crown. And this was at a time when the English looked enviously at the vast empires being carved out by Spain and Portugal. These explorers were John Cabot and his son Sebastian. John Cabot, or Giovanni Caboto, was born in 1450 in Genoa, like Columbus. At an early age he went to Venice where he took part in the great trading voyages – including one to Mecca – that were the foundation of Venice's prosperity. Young Cabot was deeply impressed by the silks, spices, and precious stones he saw, and became obsessed with the idea that a quicker and shorter sea route might be found from the West to the East. Like all the great explorers of his time, he was convinced that such a route should be found by sailing west, and in about 1484 he came to London to canvas his views to England. The merchants of Bristol, one of England's greatest ports, welcomed his scheme.

Over a period of several years expeditions under Cabot's command were dispatched with the object of finding the 'island of Brazil' or the 'island of the seven cities' which mediaeval map-makers inserted to the west of Ireland. Not surprisingly, the search proved fruitless, but in 1493 came the news that Columbus had 'reached the Indies'. At once it was decided to forget the islands and press straight on to the fabulous lands of Asia. On 5 March 1496 letters patent were issued by King Henry VII granting his 'well-beloved John Cabot, citizen of Venice, to Louis, Sebastian and Santius, sonnes of the said John, full and free authority, leave and power upon theyr own proper costs and charges to seeke out, discover, and finde whatsoever islands, countries, regions, or provinces of the heathen and infidel, which before this time have been unknown to all Christians'. The King's part of the bargain was that a fifth of all the gains resulting from the discoveries were to go into his treasury. Voyages to the west

Cabot's expedition set sail on 2 May 1497 to follow these instructions. It consisted of one ship, the Mathew, manned by 18 men. Sailing north past Ireland and then turning west, Cabot arrived at the most northerly point of Cape Breton Island, in Canada, on 24th June. He raised the English flag and took possession of the land in the name of Henry VII. This was the inauspicious beginning of England's colonization of North America.

But Cabot, like Columbus before him, thought he had found Asia. In a state of great excitement he returned to Bristol, naming a number of islands on the way, and docked on 6th August. As his reward for claiming part of the 'land of the grand Khan' he received a gift of £10 from the King.

Henry accepted Cabot's proposal that a new voyage should follow the coasts southwards as far as Japan which was thought to be near the equator) and thus arrive at the very center of the spice trade. Cabot was granted a pension of £20 and promised a fleet of 10 ships for the project. In fact, Cabot only had two ships when he left Bristol in the spring of 1498, though they were accompanied by a number of privately owned merchant ships. Cabot decided to search for a land in the far north which he had heard about from an explorer called Labrador. They drifted northwards with the Gulf Stream, and early in June reached Greenland, which Cabot named Labrador's Land. The fleet continued northwards, and the cold became more and more intense. Gigantic icebergs rose out of the mists and made their progress hazardous and slow. On 11th June the crews mutinied, and Cabot had no choice but to turn about, having failed to find the northwest passage through Greenland to Asia.

Unable then, to continue north, Cabot explored the southern coast of Greenland and then set a course west. Eventually he arrived at Baffin Island, to the far north of Canada, which, of course, he considered to be Asia. So he turned south in search of Japan. He did a little bartering in furs with Indian tribes, but in his progress down the coast he became increasingly depressed to find no signs of the legendary Asiatic civilizations. His rations were running low, so he set sail for England, arriving there in the autumn of 1498. Later that year he died.

Divided loyalties

Sebastian Cabot was somewhat less single-minded than his father. After early service for England, during which time he appears to have sailed in search of the north-west passage (1509), he was sent by Henry VIII to help the Spaniards against the French in 1512. He promptly joined the Spanish navy, and rose to a position of some seniority. In 1520 he returned to England to take charge of an expedition to Newfoundland. But suddenly deciding that e should serve his own native country he abandoned King Henry and in 1525 became commander of a Spanish-Venetian expedition 'to discover the Moluccas, Tarsis, Ophir, Cipango (Japan), and Cathay (China)'.

Sebastian's three vessels set sail from Seville in April, and in two months he reached the coast of Brazil. Turning southwards towards the Strait of Magellan, he became diverted by accounts of Spanish colonies and the enormous wealth in the country of the river Plate (La Plata). He persuaded his men to forgo the search for the spice islands and reached the Plate in February 1527.

The authorities in Seville took a dim view of Sebastian's disobedience, and on his return in 1530 he was sentenced to four years' banishment in Oran, Africa. He was, however, allowed to return after only just under three years.

Soon, however, Sebastian was again seeking employment with Henry VIII. He was unsuccessful, but after the accession of Edward VI he slowly made his way to England and in 1549 was granted a pension of £166 13s 4d. Two applications by Spain for his extradition were refused.

Sebastian played the major role in founding the great company of Merchant Adventurers, incorporated in 1551. He became its governor for life. In May 1553 his company organized an expedition to try to find ten north-east passage to the Indies 'over the top' of the great Asiatic Land mass.

Two of the expedition's three ships became trapped by ice in the frozen northern waters and their crews perished. But the third, commanded by Richard Chancellor, succeeded in entering the White Sea, from where the captain made his way inland to Moscow. This paved the way for considerable Anglo-Russian trade agreements, and was one of the many achievements of Sebastian's company.

In May 1557 Sebastian's pension was stopped, owing to the influence of Philip II of Spain, Queen Mary's husband. However, Mary restored it after only a few days. The exact date of Sebastian's death is not known, but it is probable he died later that year. His death brought an end to an era in which the Cabots family from Italy rendered magnificent services to England.

The Merchant Adventurers

The Merchant Adventurers were one of the earliest and most successful English companies which indulged in overseas trade. The Fellowship of the Merchant Adventurers London was created in 1486 and received special privileges from the King in return for their part in fostering the growing cloth trade. The Fellowship formally became a company in 1551. In the second half of the century it received almost monopolistic privileges and played a major role in extending English commerce.