Cretan civilization

Figure 1. Location of Crete.

Figure 2. Reconstruction by Evans of the north entrance to the Palace at Knossos.

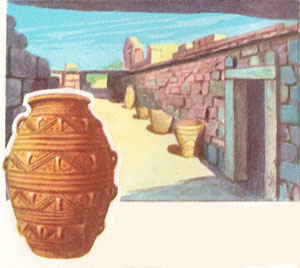

Figure 3. The royal store-rooms at Knossos, placed in a line along a corridor 40 meters and over 3 meters wide. Enormous jars contained corn, oil, and wine. Some of the oil caught fire when the palace was destroyed, and a number of the state-rooms are still black and gray in consequence. Other enormous jars, of earlier date, are decorated with a rope-pattern.

Figure 4. Priest-king fresco at Knossos.

Figure 5. Cretan artifacts.

Figure 6. Cretan artifacts.

In the middle of the Bronze Age, while the Greeks were still slowly building up their first great civilization (culminating in the siege and sack of Troy in about 1240 BC), there lived on the neighboring island of Crete another people who already possessed their own advanced civilization (Figure 1). The Greeks must have had contact with them; objects made in Crete have been found in Greek ruins of this period, and we now know that towards its close Greeks and Cretans spoke the same language and wrote it in the same way.

But soon afterwards the first 'Dark Ages' descended upon Crete and upon Greece itself. Perhaps this is why Greeks of classical times remembered nothing of Crete except a few legends – about King Minos and his great palace at Knossos; the Minotaur, a fierce monster, half man, half bull, who lived in the Labyrinth, a maze so complex that anyone who ventured inside was unable to find his way out again.

Most legends, however, have a grain of truth in them. After his brilliant discoveries at Troy, Tiryns, and Mycenae the wealthy German Heinrich Schliemann determined to see if he could find the palace of Minos at Knossos. But for various reasons he was not able to excavate at once, and he died before he could do so.

Excavations in Crete

The first person to excavate the site at Knossos was an Englishman, Sir Arthur Evans. He began his work in 1900, and continued it almost without interruption for 25 years. The result was astounding. He not only discovered the palace of Minos: he spent over £250,000 on restoration work, so that the present-day visitor can have a good idea of what the palace must have been like in the days of its splendor (Figure 2).

Knossos is not the only archaeological site on Crete. Other archaeologists have excavated a second palace at Phaistos in the south, second only to Knossos; and villas have also been found at Hagia Triada and Mallia.

A characteristic feature of all these remains is the complete absence of fortifications and defense walls. Evidently Crete enjoyed a prolonged period of peace. Probably it was protected, as the later Greek historian Thucydides said, by a strong fleet.

Knossos

Long before Evans had finished his excavations, it was clear that he had found a magnificent palace, with the colossal area of more than 100 meters square (Figure 3). The corridors, rooms, and courtyards of the various floors were very complicated, with a Grand Staircase of no fewer than five flights of stairs. The building was imposing, yet at the same light and graceful, with downward-tapering columns and open light-wells, and was decorated with remarkable wall-paintings. The Throne Room still contained a gypsum throne, the oldest in Europe. But perhaps the most remarkable of all were the plumbing and sanitary arrangements, which have never been surpassed until the modern day.

This great palace, survivor of many earthquakes, was finally destroyed by a disastrous fire. The marks of the smoke show that this happened on a spring day when a strong south wind was blowing. But what caused it? The answer is still unclear.

Cretans in wall-paintings

The wall-paintings discovered during the excavations of the palaces at Knossos and Phaistos give us a fairly clear idea of what the ancient Cretans looked like – slender people, with black wavy hair and aquiline noses. Men were clean-shaven, and wore tight belts and usually a short kilt.

Figure 4, of the so-called Priest-King fresco at Knosses, shows a young prince crowned with peacock feathers.

Fashions in women's clothing, as shown in wall-paintings, were elegant and remarkably similar to those of 1900, the year in which the paintings were discovered. Women wore low-cut blouses with puffed sleeves, tight waists, and flounced skirts colored in bands of blue, yellow, and red. Hair was long, in various elaborate styles.

Artifacts

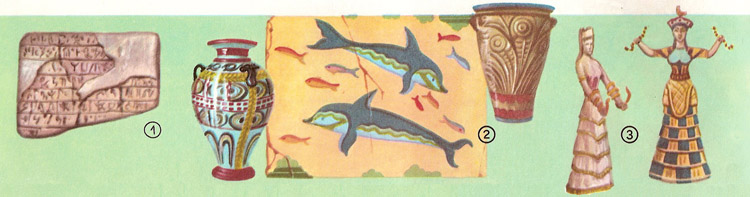

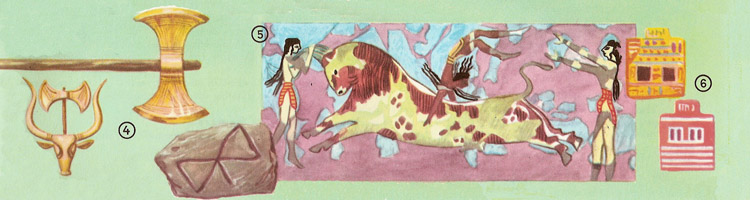

These notes refer to Figures 5 and 6.

1. A tablet with Linear B inscriptions (see Cretan language). Each character represents, not one letter, but one syllable. More than 80 different characters were used.

2. This is a detail of a wall-painting in the "Queen's Megaron" (hall) at Knossos, and some painted vases discovered during the excavations. The Cretans, who were a seafaring people, liked to paint various sea-creatures, such as fish and octopus, and also tufts of seaweed. Wall-paintings and decorations were highly artistic and were executed in a remarkably modern style.

3. Unlike other peoples of antiquity, the Cretans do not appear to have built temples for their gods. Religious ceremonies took place wither in open-air enclosures on hill-tops, or in caves o the mountainside, or in small shrines within the house.

The chief divinity seems to have been a goddess. Beautiful little statues of her, such as these two, found at Knossos, show her wearing Minoan dress and holding two snakes.

4. One of the most important religious symbols of the Cretans was the 'labrys' (axe with two blades). This symbol, often associated with the head of a bull, is not only pictured in caves where the gods were worshipped; it is also seen in wall-paintings or carved on pillars within the palace.

The bull was evidently a sacred animal. It has been suggested that this was because the roaring of a bull resembles the sound of an earthquake – Crete has suffered many times from these over the centuries.

The story of the Minotaur may well have sprung from this cult of the bull. "Minotaur" simply means "bull of Minos," and "labyrinth" "place of the labrys."

5. This fresco from Knossos shows the dangerous sport of bull-leaping, in which girls as well as boys are depicted as taking part. According to the picture, the athlete caught hold of its horns as the bull charged, and somersaulted over its back: but it is doubtful whether this can in fact be done.

6. The front of Cretan houses, painted on faience tiles.