Elizabethan art and architecture

Figure 1. Nonsuch Palace, Surrey (built 1538–1547), was the most extraordinary palace that Henry VIII built or enlarged. The life sized stucco figures of gods and heroes set the fashion for Elizabethan plasterwork. Nonsuch was demolished in 1682–1683)

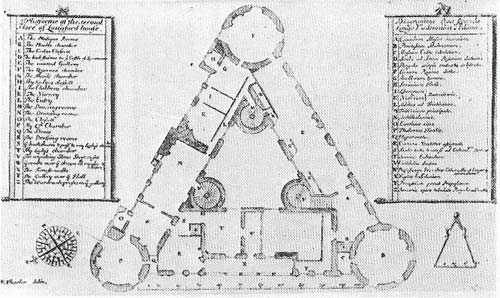

Figure 2. The plan of Longford Castle, Wiltshire (1580), in the form of a triangle with a round tower at each corner, symbolizes the Trinity, God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost. Such houses were designed rather for ceremonial forms of life than for comfort.

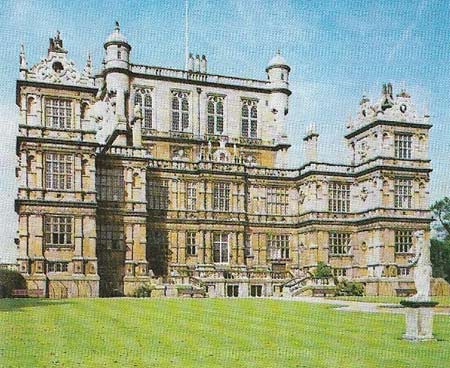

Figure 3. Wollaton Hall, Nottingham, built in 1580, was designed by Robert Smythson for Francis Willoughby, a great landowner of the Midlands and an early coal magnate. Set on a hilltop and flaunting towers of bizarre outline and a great central belvedere, Wollaton Hall epitomizes the self-confidence of the last years of the reign of Elizabeth. Although it had prominent classical pilasters, there is no classical spirit of balance and proportion. Few 16th-century architects' names are known today.

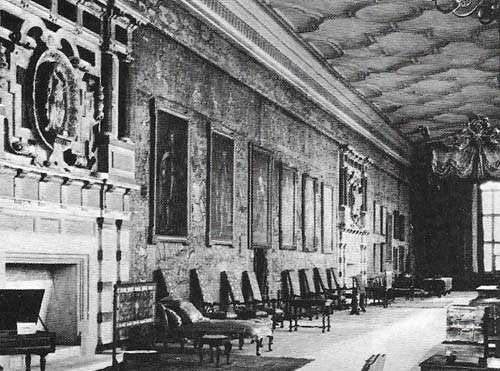

Figure 4. The long gallery, such as this one at Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, was a typical feature of the houses of Elizabethan nobility, many were built in the roof-space of the house and had good light and views. Long galleries were used for exercise in bad weather and to display collections of portraits in a sumptuous environment.

Figure 5. The ballroom of Knole House, Kent, has a rich chimney-piece of variously colored marble and alabaster (shown here) and a marble frieze in high relief of grotesque monsters, a typical effect of brilliant and barbaric splendor. The house was remodeled internally for the Earl of Dorset in 1605–1608.

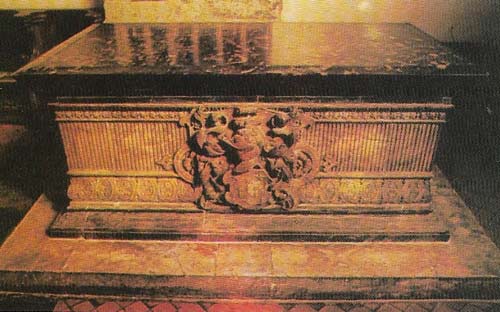

Figure 6. Funerary monuments, such as this one of Thomas Gresham (d. 1579), a merchant and founder of Gresham's Exchange, London, were objects of great expenditure for many Elizabethans. This one, built before Gresham's death, cost him £800. Its free-standing tomb chest of traditional form is remarkable for the purity and restraint of its classical decoration, qualities rare in Elizabethan art. Often funerary monuments included portraits sculptures of the dead man kneeling in prayer with his wife and children. Such portraits were stereotyped, but their setting was luxuriously decorated.

Figure 7. The Ermine Portrait of Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) was painted by either Nicholas Hilliard or William Segar in about 1585. Portraits of the queen were commonly produced for the houses of the nobility, and they often included literary or poetic symbolism. In this work, the ermine is intended to denote purity, virginity and chastity, and the rubies on her necklace come from the Crown Jewels. Such portraits contributed to the assumption by Elizabeth of mythical status during her lifetime. Many other symbols were used in other paintings: a rainbow in one work was accompanied by the words "No rainbow without the sun", and there were eyes and ears in her clothes.

England in the later 16th century was artistically isolated. The primary reason for this was Henry VIII's break with the Church of Rome in the 1530s, which made cultural contact difficult with the leading artistic countries – Italy, France and Spain – all of which were Catholic. Thus English art developed its own strong and peculiar character, even though many leading artists and craftsmen were foreigners, often religious refugees. The main art forms were portraiture and country house architecture.

Holbein and English portraiture

In the 1530s the German painter Hans Holbein (1497–1543), one of the outstanding Northern European artists of his generation, settled in London. There he produced an unforgettable image of the king, was widely employed to paint portraits of courtiers and even commissioned by his royal master to record the features of prospective wives. Holbein combined boldly economical design and virtuosity in depicting rich costumes with an astonishing power to recreate the physical presence of his sitters.

|

| Hans Holbein, the German portrait painter, was in England 1526–1528 and 1532–1543. His art was vividly realistic. This work, of 1538, shows Princess Christina of Denmark when she was 17, and being considered by Henry VIII as a prospective bride. The full-faced view gives the clearest and least flattering impression of her looks. Holbein's style was popular until 1600. |

So popular was his style that he set his stamp on English portraiture throughout Elizabeth's reign. Elizabeth herself, acutely aware of the power of the visual arts, allowed only certain images to be used in her pictures. Many portraits of the queen made for the nobles' collections included symbolical elements emphasizing her power and the effects of her favor (Figure 7).

Only in miniature painting did Holbein find worthy successors. Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver (died 1617) raised this art form to European preeminence. The conceits and metaphors of the Elizabethan poets have their parallel in the miniature, with its symbolic language of love.

Tudor architecture

A similar strain of fantasy on an incomparably greater scale than in the miniature can be found in the Elizabethan "prodigy" houses. Henry VIII's palace of Nonsuch, Surrey (Figure 1), introduced a novel flamboyance to domestic architecture. The decoration of its external walls, stucco figures in relief set between panels of slate, was the work of French craftsmen who had previously been – employed by Francis I at Fontainebleau.

Briefly, during the 1550s, the Duke of Somerset, Protector to Edward VI, and several of his political associates, introduced a more serious classicism: first in Somerset House, London, (1547–1551) and then at its climax in John Thynne's great house at Longleat, Wiltshire, which gained its present form in the 1570s. Later Elizabethan architecture, however, developed towards an unclassical preoccupation with striking silhouettes, dramatic projections and recessions of mass, enormous areas of glass, and strapwork ornament. Wollaton (Figure 3) and Hardwick (1590–1596) halls, both designed by Robert Smythson (c. 1536–1614), as well as such Jacobean mansions as Bramshill, Hatfield and Audley End all have this bizarre and inventive character. Some, such as Longford Castle (Figure 2), have symbolic forms.

Many magnates who built prodigy houses were impelled to such extravagance by the prospect of entertaining the queen, whose annual progresses took her far and wide through her kingdom. Richly decorated rooms were required, and plasterwork – white or picked out in heraldic colours – polished marbles, alabaster and stones, and even stained glass, all contributed to the effect of dazzling sumptuousness. The chimneypiece (Figure 5) usually carried the most elaborate concentration of carved ornament. By the late 16th century the great hall was beginning to lose the importance it had possessed in medieval times and more private rooms for the family, in particular the great chamber and the long gallery, had more attention lavished on them (Figure 4).

Sculpture and the applied arts

Another opportunity for an elaborate display of sculpture was the funerary monument [8]. Many imposing Elizabethan monuments survive, brilliant with heraldic colours and Building. Artistically the best of these sculptures were fashioned by immigrants from the Low Countries – men such as Cornelius Cure (died 1607) and Maximilian Colt (flourished 1600–1645) whose best known works are the monuments of Mary, Queen of Scots and Elizabeth I respectively in Westminster Abbey. In general, however, the standard of Elizabethan figure sculpture was low. This mattered little because contemporary taste was universally naïve, delighting in rich textures, intricate detail and garish coloring.

The Tudor period was the heyday of the jeweller and goldsmith. Foreign artefacts were readily obtainable in England, and there is no clearly definable English style. Only miniature painting, considered a form of jewelry (Hilliard was himself a goldsmith by training and probably designed the settings for many of his miniatures), is an exception. Among full-scale goldsmith's plate, the most typically English was the standing salt. Even Holbein designed such salts as well as other kinds of plate and jewels.

|

| The standing salt, such as this example made in 1549, was a decorative object for the dinner table with its utilitarian purpose disguised. Precious materials, Laborious workmanship and bizarre forms all held a fascination for Elizabethans. Jewelry and objects made of gold were easily portable and made good gifts; as a result, European style was more uniform in the medium than any other in the 16th century. Nevertheless the standing salt was peculiar to England. Goldsmiths were legally bound to stamp each piece with the date, the place where it was made and the maker's initials, but unfortunately the key to Elizabethan marks has been lost. |

During Elizabeth's reign the arts in general had a hesitant start that was affected by the political and religious uncertainty of the 1560s, but developed greater and greater confidence. They did not reach their fullest flowering until the early years of the 17th century, when a monarch prepared to lavish patronage on the arts had taken the place of a parsimonious one.