early western Asia

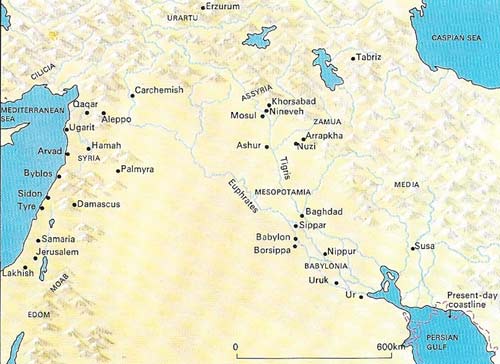

Figure 1. The drama of ancient western Asia was centered on the riverine plains and adjacent hills and mountains between the Mediterranean and Caspian seas and the Persian Gulf. The area was dominated by the Tigris and Euphrates, the land between being Mesopotamia, but the term is used loosely for a wider area round the rivers. The silt they and their tributaries produced and the water diverted from them by irrigation helped the growth of the towns and later of the capitals of Babylonia and Assyria, whose power and conflicts provided the framework for the history of their times until their decline in the seventh and sixth centuries BC.

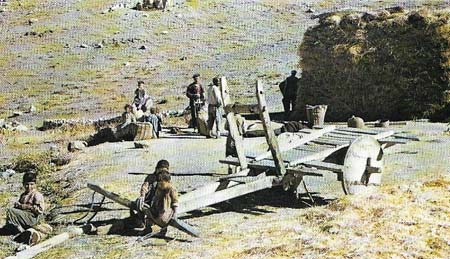

Figure 2. The wheel was probably invented in Mesopotamia during the fourth millennium. At that time it was constructed not of rings with spokes but of solid circular disks of planks clamped together, with a "tire" of broad-headed nails driven into the outer rim. Spokes came later, but the earliest type of wheel still survives in remote areas; this one, for example, is found in a small village in eastern Turkey near Lake Van. Although many notable monuments had been built without the aid of the wheel, including the pyramids, its introduction greatly facilitated farming and transport and proved central to the development and spread of Mesopotamian civilization.

Figure 3. Fragments of ivory boards each 33 centimeters (13 inches) by 15 centimeters (6 inches) were found covered in sludge at the bottom of a well in a royal palace at Nimrud. The boards had a raised margin round a recessed portion that probably contained a mixture of beeswax and pigment as a base for a cuneiform text. This unrecessed board carried Sargon's name and the title of the "book" of omens taken from celestial observations.

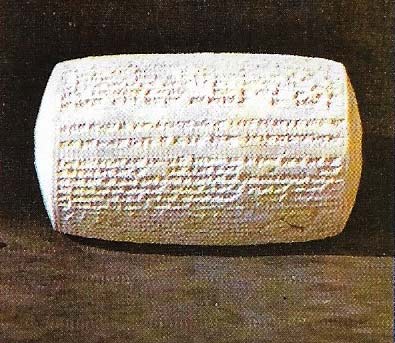

Figure 4. Hollow "barrel cylinders" of clay were at times used by the Assyrians for recording texts in cuneiform. This one, about 17 centimeters (6.7 inches) by 10 centimeters (4 inches), refers to Esarhaddon and gives a general summary of his conquests and achievements. It also tells of a new palace he has built, with roof-beams of cedar from the Amanus mountains and "doors of sweet-smelling cypress wood". It dates from about 670 BC.

Figure 5. This monolithic basalt water-tank of the time of Senna-cherib (r. 704–681 BC) was reassembled from small fragments, and measures about 3.2 meters (9.7 feet) square by 1 meter (39 inches) high. Four corner-figures, almost in the round, represent the god Ea holding a water-dispensing bottle, as do the four figures facing outwards from the center of each of the four sides. Two priests in fish-garments and holding ritual vessels turn to each of these figures. Two of the sides carry the inscription identifying the king. The detailed interpretation is uncertain, but the water element is clearly treated in an arcane sense; Ea, as god of the deep and of knowledge, may be intercessor between heaven and earth.

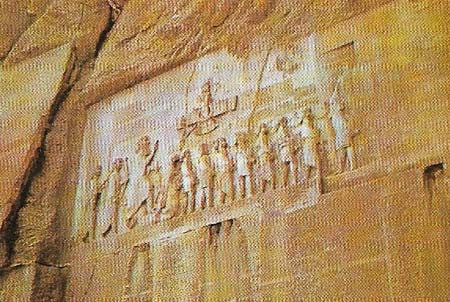

Figure 6. Darius the Great of Persia (r. 521–486 BC) defeated nine princes to secure his throne. He recorded his achievement in detail on the face of the rock at Bisutun in western Iran, on the route from Mesopotamia to Teheran. The sculptures show two attendants behind Darius himself, his right foot planted on the pretender Gaumata, and nine rebels in captivity. The adjacent rock faces bear 11 short cuneiform inscriptions identifying Darius and his foes, with a long trilingual inscription that confirmed and amplified modern knowledge of the scripts, previously known only by similar, much shorter trilinguals.

The historical term "western Asia" comprises the modern states of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, and perhaps Afghanistan. In antiquity the center of the stage was occupied successively by Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Persians, with Hittites, Hebrews, and Phoenicians also playing their part, and Elamites, Hurrians, Urartians, and Aramaean – to list only some of the best known – in the wings. Their civilizations were mostly lost to knowledge after their fall, and so remained through the Dark Ages; and their recovery was long delayed by restricted access to and exploration of their lands.

The development of writing

Rapid advances in knowledge came in the mid-nineteenth century, very much as a result of the decipherment of the Old Persian cuneiform script (Figure 6), which through trilingual inscriptions (Old Persian, Babylonian, and Elamite) provided the key to the immeasurably greater bulk of Assyrian, Babylonian, and Sumerian texts in cuneiform writing of a more difficult kind.

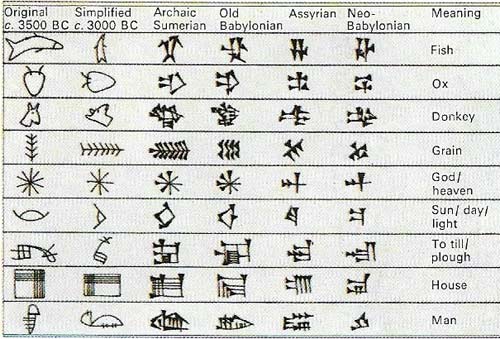

Cuneiform developed from the pictographic script first used by the Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia late in the fourth millennium BC. Their language fell largely into disuse early in the second millennium, but the cuneiform script in which it had been written was used by their political and cultural heirs, the Babylonians, to express their own Semitic language, known as Akkadian, although it was entirely different from Sumerian. Other speakers of Akkadian, in particular the Assyrians, also used cuneiform. The same script, with relatively minor variations, was used elsewhere in western Asia to express other quite different languages, such as Hittite, Elamite, Hurrian, and Urartian; and the same principle – varying groups of cuneiform (wedge-shaped) impressions – was used for the simpler Old Persian script of the Achemenid Empire and for the alphabetic script of the Phoenicians.

Deciphering the inscriptions

The excavations and study of the cuneiform-inscribed clay tablets and of similar inscriptions on stone and other materials was stimulated by the announcement, in 1872 of the decipherment of an Assyrian version of the biblical story of the Flood, found on a tablet at Nineveh in northern Iraq. Understanding other cuneiform inscriptions was made easier by the Semitic character of the Akkadian language in which many were written – it was related in varying degrees to such known languages as Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic. The information provided by the inscribed material (nearly all in cuneiform, but with additions particularly from Old Testament Hebrew, Aramaic and hieroglyphic Hittite) has been supplemented by further surface discoveries and, particularly for the prehistoric (generally pre-writing) periods in western Asia, by archaeological excavation.

|

| Sumerian writing probably evolved from the needs of public economy and administration. As the Sumerian city states developed, records were needed of goods moving in and out of the towns. Clay or gypsum were originally attached to objects and bore a seal-impression identifying the owner; line drawings of the objects followed. Drawings were gradually simplified to signs. Later the sign for a common word such as ti (arrow) was used for "ti" sounds generally. (Ti also meant "life".) The shift to phonetic representation led to the development of written symbols for entire languages. |

The geographical background

There are significant geographical variations in the territories covered by the ancient civilizations of western Asia. The coastlands of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean give way more or less steeply to the Anatolian plateau of central Turkey, mainly watered – around its central desert – by rivers flowing towards those two seas, with the Hittite capital in north central Anatolia close to the modern village of Bogazkiiy within the bend of the River Kati Irmak.

In the south, the Taurus range impedes the way up from the Cilician plain, while in the extreme east and northeast, high ranges (including Mount Ararat, 5,185 meters (17,011 feet) high) restrict movement and cradle the sources of the Euphrates and Tigris. These two rivers, after flowing westwards to begin with, both turn southeast to form most of the Fertile Crescent, watering the plains of Mesopotamia where the capital cities – notably Babylon, Ashur, and Nineveh – of their major empires were built (Figure 1). To the west of Mesopotamia lies the desert, and still farther west are the Jordan and Orontes valleys and eventually the Mediterranean coastlands. East of Mesopotamia, valleys wind through the harsh mountains of the Zagros to the dry Iranian plateau with the Elamite capital Susa and the Achemenid Persian capitals Pasargadae and Persepolis.

|

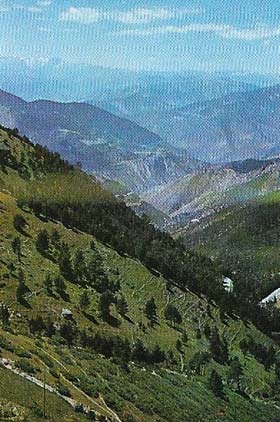

| A main route from Trabzon and the eastern Black Sea coastal area of Turkey leads southwards up the 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) Zigana Pass, which is open for most of the year. The route continues through high, mountainous country to Erzurum, Tabriz, and Teheran, thus serving as a northwestern gateway to Armenia and Persia. It also provided a trade route between those lands and places accessible by ship from Trabzon. The Persian "Royal Road" between Susa in Persia and Sardis in the west used a more southerly route through Diyarbekir and Ankara, where the going was easier. The lands south of Trabzon are typical of much of eastern and northeastern Anatolia. |

Excavations have shown that the settlements of prehistoric man in some of these areas date back to as early as 9000 BC. Agriculture began sometime later. The cultivation of grain ("man's most precious artefact") assured a steady food supply, which led successively to expanding populations, release of labor for pursuits other than food-producing, specialization in craft, trade, government and religion, and so to the development of civilized societies from villages and towns to kingdoms and empires.

|

| A sun-dried clay figurine from a ninth-century BC palace at Nimrud in northern Iraq bears the inscriptions, impressed in the clay on the back in Assyrian cuneiform, "Come in, favorable demon; go out, evil demon". Such figurines lay in the brick-built foundation-boxes that are commonly found in the corners and beside the door jambs of important Assyrian buildings of the first millennium. |

Wild cereal plants grew over much of western Asia, and their cultivation seems to have come first in the highland zones, notably in the Zagros mountains of eastern Iraq and western Iran and on the south Anatolian plateau. But as the grain-producing capacity of an inhabited area was bound to be a major factor in accelerating or retarding man's development, the fertility of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, particularly with the addition of artificial irrigation from those rivers and from their main tributaries (the Habur, Upper and Lower Zab, and Diyala), gave the predominant prosperity in western Asia to the civilization of the Mesopotamian and southern plains.