Florentine art 1400 to 1460

Figure 1. The Cathedral, Florence, was begun by Arnolfo di Cambio c. 1300. By the early 15th century construction had reached the octagon. Advice was sought in all directions for covering the 40 meters (130 fet) opening before, in 1420, Brunelleschi's solution was accepted: a dome of double herringbone brick shells and stone ribs, which could be built without scaffolding. The dome was completed in 1436, and the lantern on top begun in 1446.

Figure 2. "Tribute Money" by Masaccio (c. 1427) is the dominant scene in a cycle of frescoes in the chapel of the Brancacci, S. Maria del Carmine, Florence, detailing the story of Peter. The series was begun c. 1424 by an older artist, Masolino. The subject was interpreted by theologians as one of the main proofs of the supremacy of the pope as Vicar of Christ.

Figure 3. "Tarquinia Madonno" by Filippo Lippi (1437) was an early work, painted in tempera on panel, after a period of close imitation of Masaccio and a journey to north Italy. A know-ledge of Flemish painting accounts for the informal, domestic treatment of the subject and the dark, rich colors.

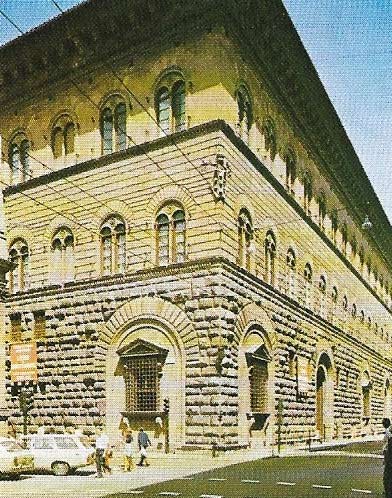

Figure 4. The Palazzo Medici-Riccardi was built by Michelozzo c. 1444–1460 for Cosimo de' Medici who had rejected a design by Brunelleschi as being too ostentatious. Michelozzo's design conforms superficially on its exterior to the traditional Florentine merchant's house, although a heavy classical cornice replaces the projecting eaves. Inside it has a splendid Renaissance arcaded court.

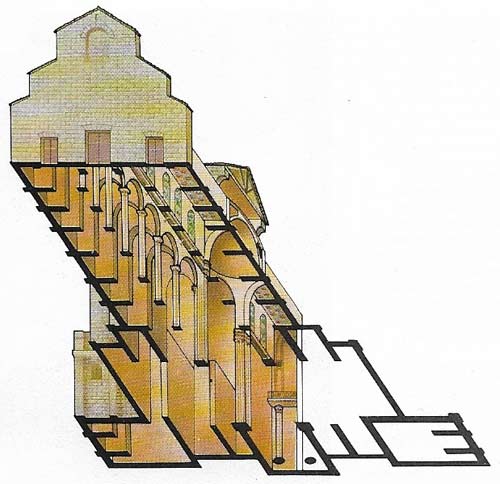

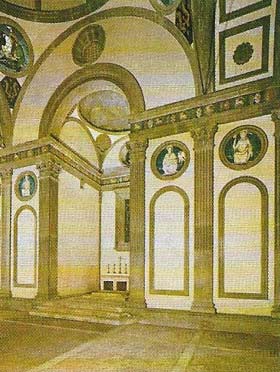

Figure 5. San Lorenzo by Brunelleschi was begun c. 1418 with the Medici Sacristy, attached to the left transept. The church was largely funded by the Medici family (Cosimo is buried under under the central dome). Although the facade was never completed, Michelangelo added.

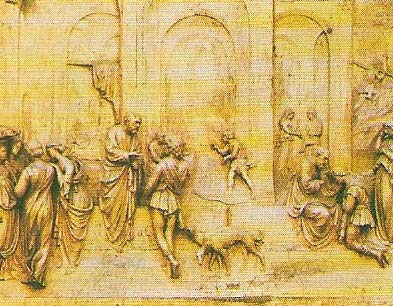

Figure 6. Solomon and Sheba by Lorenzo Ghiberti, from the "Paradise Doors" of the Baptistery (1425–1447) (gilt bronze) is one of ten Old Testament reliefs from the third set of doors (his second), all commissioned by the guild of businessmen who had responsibility for the Baptistery. The reliefs were modelled in wax and cast separately, chased to a very high finish and then set into a massive framework. A rich leafy border frames the opening. Ghiberti, one of the most notable figures of the early Renaissance, left Florence in 1400 but was recalled a year later to take part in a competition that led to his casting the Baptistery's second pair of doors.

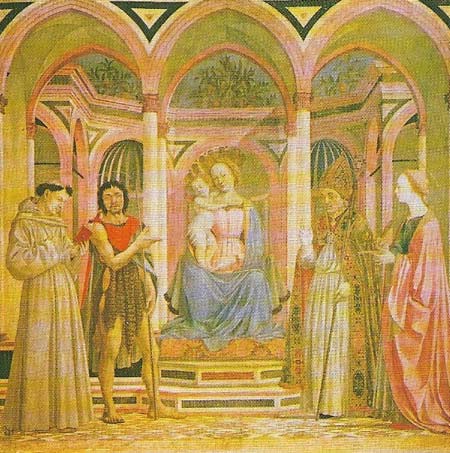

Figure 7. "Saint Lucy Madonna" by Domenico Veneziano (c. 1445) is an altarpiece of the type known as a sacra conversazione, which implies a close and informal relationship, spatially and psychologically, between the Madonna and the saints. The single panel generally supplants the polyptych, but its hierarchical division is often preserved, as here, by a subtle design of painted architecture. The perspective construction is extremely sophisticated and the colour and light are exceptionally unified. A predella with five small narratives of the lives of the saints was formerly attached.

The opening years of the 15th century in Florence were marked by costly and alarming wars, which the city survived somewhat luckily, and by political upheaval. These circumstances led to high taxation, the ruin or exile of several prosperous families and a great decline in the city's absolute wealth; but they also provoked a resurgence of patriotism, a consciousness of the city's cultural traditions and supposed Roman origin, and public competition between patrons.

The cathedral dome

The building of the dome (Figure 1) of the Florentine cathedral by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) symbolized the new condition of the city; it seemed the realization of an impossible civic dream, it was achieved by the study of medieval and Roman engineering, and inevitably it was compared with the greatest triumphs of Antique architecture. The dome is not classical in detail, except in its latest elements, the lantern and the four semicircular exedrae which act as buttresses round its drum; and it is characteristic that even these, formed as they are out of classical pilasters, capitals, entablatures, scrolls and shell-niches, are not classical in function. Brunelleschi solved with extraordinary confidence the problem that remained fundamental to most later Renaissance architecture of applying the Antique formal vocabulary to building types of a new age. To some extent he was helped by the example of Florentine Romanesque architecture, notably the Baptistery and SS. Apostoli. His determined use of traditional local materials, a dark gray stone known as pietra serena, brick and whitewashed stucco, even colored-marble facing, also meant that in their colours his buildings were much more closely related to the vernacular than to antiquity. The strong contrasts inherent in these materials gave his buildings very distinct articulation of their parts.

|

| The Pazzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence, was designed by Brunelleschi c. 1430 to be both the private chapel of a wealthy family and a chapterhouse. The plan, a lateral domed rectangle with a smaller domed chancel, is a development of Brunelleschi's earlier Sacristy in San Lorenzo (1420–1428). But the elevations articulated characteristically in dark pietra serena on white stucco are so much more logically composed that it is generally considered his most perfect building. The exterior is only partially to his design. |

Florentine sculpture

Clarity of structure and evidence of intensive study of the Antique also characterize the mature sculpture of Donatello (1386–1466), whose "Saint Mark" (1412) made the first forceful statement all'antica (in imitation of the Antique) – a statement about the nobility and gravity of man such as Cicero might have made, and in a language which revived that of Roman sculpture. It was followed by a long series of saints and prophets which peopled the public buildings of Florence with heroic, alert and intensely personal beings, each an embodiment of a particular virtue.

|

| "Saint Mark", by Donatello (c. 1412) was made for the Weavers' Guild for their niche on the guild hall, Orsanmichele. Donatello imitates Antique statues not only in details, such as drapery folds, but also in the whole design. The balanced movement of the figure's structure (contra pposto) is expressed with clarity through and by the superimposed drapery, and there is no trace of the swinging posture and elegantly curved forms characteristic of late Gothic sculpture. The solemnity and intensity of expression is typical of Donatello, but his rugged simplicity is now exaggerated by the loss of gilt details and weathering. |

|

| "David" by Donatello (c. 1435) was made for the Medici. Sensual and pagan, it was the first convincing revival of the canons of the classical nude. The head derives from a Roman "Antinous". |

Donatello's work is not dependent for its expressiveness on the beauty of craftsman-ship and rich materials; in this respect he exemplifies an aesthetic revolution, enunciated in Alberti's essay On Painting (1435), which advocated a revival of the Antique standards of simplicity, even austerity, and eloquence. But Donatello's contemporary Ghiberti (1378–1455), a much less radical character, found an elegant compromise between Gothic ideals of beauty and the new style. A matchless craftsman, he won for this reason the competition (1401–1402) for the first set of gilt bronze doors for the Baptistery; their design and details owed practically nothing to antiquity. But the second set – the "Paradise Doors" – are much more lucid in design and participate in the revival in many ways; and in the conspicuous use of mathematical perspective, effectively a rediscovery of Brunelleschi's, they show where his new allegiance lay (Figure 6).

Florentine painting

Perspective was very quickly exploited by the youngest of the pioneers, the painter Masaccio (1401–1428). It allowed him to place objects in apparently rational relationships in space; but he saw that the visual laws it expressed, when applied consistently, controlled not only the boundaries and intervals of space but also the drawing of forms to suggest three dimensions. The result was realism in a new sense, the realism of structure. But the same way of thinking, about space and form as unities, also led him to the first true pictorial light, unified and rational to the extent that shadow was its inevitable companion. In his "Tribute Money" (Figure 2) light as much as linear perspective produces a convincing reality. Like Brunelleschi, he was inspired by Tuscan tradition, particularly Giotto, and by antiquity, in his case a repertory of realistic and expressive forms. His art has the same tone of austerity and moral seriousness as Donatello's.

No painter changed the course of his art in so short a life as Masaccio did. He simplified formal problems to make them amen-able to laws, and some of his followers, such as Paolo Uccello (1397–1475), continued in this way; most, however, applied his discoveries to complexities more in line with both Gothic traditions and natural appearances. Fra Angelico (c. 1387–1455), indeed, owed as much to the example of late Gothic painters such as Lorenzo Monaco (died 1424). Filippo Lippi (c. 1406–1469) (Figure 3) and Domenico Veneziano (c. 1410–1461) further modified the new style towards a descriptive naturalism, the former by responding to Flemish art, the latter by an intenser study of reality and especially of light. Domenico's "Saint Lucy Madonna" (Figure 7) represents the most advanced stage reached in Florentine painting by the mid-15th century, and it exemplifies the dominant type of altarpiece – in a single, rectangular, window-like frame – then current.