humanism in the Renaissance

Figure 1. The woodcut shows a lecture being delivered by Cristoforo Landino. Landino was one of the most widely read commentators on classical literature and a professor at Florence. His principal work was a study of Virgil and Dante; he also translated the works of Aristotle. Landino was much interested in politics, one of the circle of Lorenzo de Medici, he believed on the freedom of the citizens. In his Disputationes Canaldulenses (1475), he discussed one of the central questions of philosophical speculation; namely the relative advantages of the active as distinct from the contemplative lifestyle.

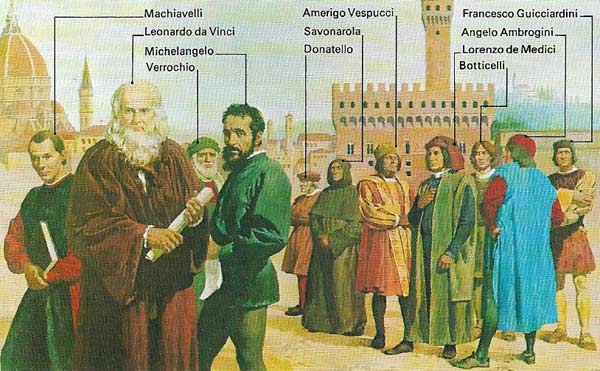

Figure 2. Prominent figures of the Florentine Renaissance, pictured here, often worked in many cultural and political fields. Lorenzo de Medici combined diplomatic activity with artistic patronage and poetry, Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540) was a political and historian and Michelangelo a poet, painter, sculptor and architect.

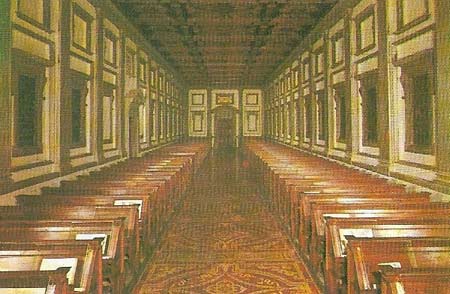

Figure 3. The rich library of Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449–1492), grandson of Cosimo de Medici (who built the Bibliotheca Marciano in St Marco Florence), became a public library in 1571. Housed in a building by Michelangelo.

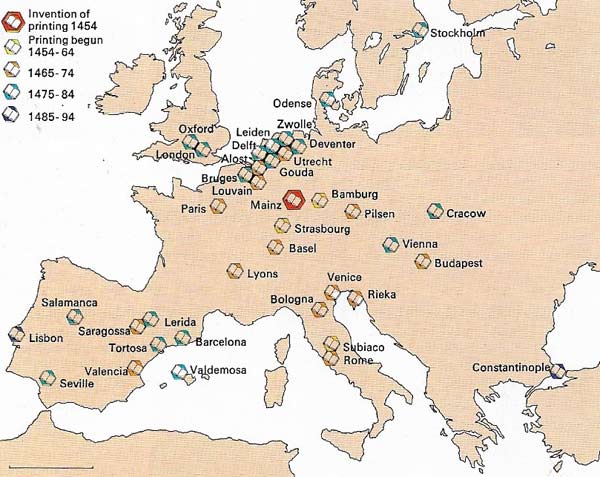

Figure 4. The new humanist learning of the centuries of the Renaissance would not have had so much impact but for the invention of printing in the mid-15th century. The map shows those European cities that had sizeable printing presses between 1454 and 1494. By 1500 Italy had 73, Germany 50, France 45 and England only 4. Although the printing press was extremely important, secular literacy was still not very extensive until the spread of education during the Reformation.

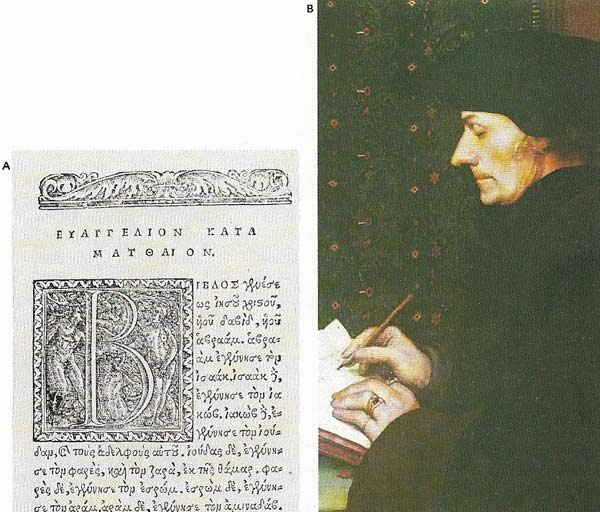

Figure 5. Erasmus of Rotterdam (B) more than any other scholar represents the humanist scholarship of Northern Europe. He combined the Italian interest in the classics and textual scholarship with the religious and devotional movements of The Netherlands. To return to the Church of the Apostles he worked to produce a pure Greek text of the New Testament (A) in the hope of ending religious dispute.

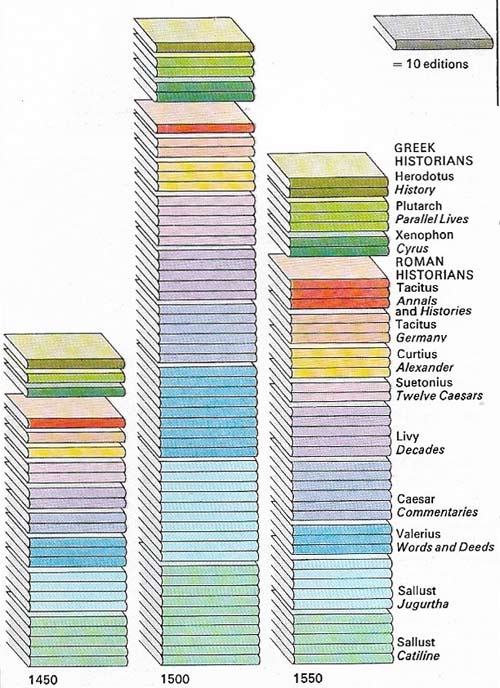

Figure 6. Editions of classical texts were produced in great numbers following the re-emergence of interest in the classics and the invention of printing. The diagram shows a survey of classical book production, 1450–1600. Beginning in Italy, the editing of texts spread to France, Germany and England by the 16th century. That century's interest in Livy and Caesar gave way in the 17th century to a greater interest in Florus and Tacitus. Perhaps more than two million copies of classical texts circulated in Europe between the invention of printing and the year 1700.

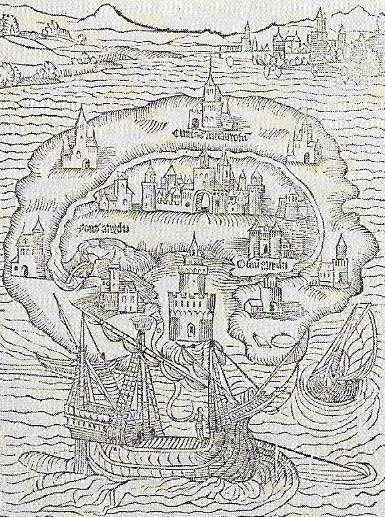

Figure 7. A blueprint for the perfect republic – Utopia – was presented by Sir Thomas More in 1516. It described the communal ownership of land, the education of men and women alike and religious toleration. As a humanist More believed that all could by their own endeavors improve the quality of their lives. In particular humanists thought that learning would teach men how to govern and serve the commonwealth. Often they advised rulers: at the court of Henry VIII the humanist "commonwealthmen" advised the government on social policy.

It is impossible to ascribe precise dates to the Renaissance. The traditional picture of a rebirth of creative thought and learning after the dark years of the Middle Ages has rightly been discarded. The new learning was not wholly original, and there was no dearth of creative thought in the Middle Ages. But this modification does not detract from the importance of the Renaissance, which from the 14th to the late 16th centuries produced the growth of a more secular spirit, a renewed interest in classical civilization and an increased respect for literature.

|

| Renaissance intellectual life was characterized by a desire to emulate the scholars of Greece who had embraced all philosophical and rhetorical knowledge. The Florentine academies were often modelled on those of Plato and Aristotle, who are pictured here engaged in animated discussion in a relief by Giotto (1266–1337) from the campanile of the Duomo in Florence. |

The classical revival

Interest in the classics was promoted by Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374) who worked on classical texts and wrote poetry in Italian and classical Latin. The prosperous towns of fifteenth-century Italy became the centers of classical scholarship, which was pursued outside the universities and under the patronage of urban patricians interested in the civilization of the pre-Christian world. Through the residence of a Byzantine scholar, Manuel Chrysoloras (c. 1350–1415), Florence became famous for Greek studies and Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) established an academy for the study of Plato's philosophy. The concentration on classical texts owed something to the medieval interest in Arabic translations of the ancients, but the textual scholarship of men such as Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457), who used philological investigation to discover pure texts of the classics, was completely original.

In Italy, burgher patronage and the casual acceptance of a worldly Church meant that the new learning was predominantly secular. Patrons and scholars were fascinated by the achievements of man and came to believe that on his own he had real power to shape his own destiny. They looked back to a time in which human achievement had reached its peak – to the past of classical Rome. The new learning was named humanitas (humanism) by Leonardo Bruni (1370–1444), who wrote a History of the Florentine People inspired by classical models.

Since Italy was the center of the Mediterranean trade routes the movement soon spread. Those fighting in the Italian wars took back books to the court of Francis I (1494–1547), who encouraged the new scholarship. By the mid-16th century the influence of Italian humanism on French scholarship was evident. French humanists such as Lefhvre d'Etaples (1455–1536) and Guillaume Budé (1468–1540) embarked upon etymological and philological studies of Greek and Roman texts and of their own institutions and codes of law.

|

| Guillaume Budé was the father of Greek studies in France and introduced the new sciences of philology and etymology. His critical study of Justinian's Digest, a compendium of Roman civil jurisprudence, showed how the text had become corrupted over the centuries. Budé demonstrated to the French humanists how language and law, as all institutions, were affected by time and change. |

The growth of printing

The printing press was another factor encouraging the rapid northward spread of Italian scholarship. Venice became a major center for the printing of Greek and Latin classics and patristics. In conjunction with the scholars of Germany and The Netherlands, printers produced new editions of the classics (Figure 6) and works by the Italian humanists.

In The Netherlands and Germany, however, the influence of Italian humanism was tempered by the new devotional movements such as the devotia moderna. Gradually new ideas were admitted into the structure of medieval scholasticism and the Christian philosophy of St Thomas Aquinas. The interests of the northern humanists were less secular than those of their Italian counterparts – although their concern with a pre-Christian culture and more personal religion led to some clashes with the Church. Their philosophy is best exemplified in the work of Desiderius Erasmus (c. 1466–1536) of Rotterdam (Figure 5B). Erasmus applied the new textual scholarship to the production of a pure Greek text of the Scriptures (Figure 5A) and by 1516 he had published a translation of the New Testament, based on the Greek texts that he had collected. If Erasmus shared some of the Italians' beliefs in the self-sufficiency of man, his humanism was diluted by mystical piety.

In England, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester (1391–1447), was a patron of the new learning. After 1490 the teaching of William Grocyn (c. 1446–1519) made Oxford a center of Greek studies and Thomas Wolsey (c. 1475–1530) built a college at Oxford (now Christ Church) to be devoted to the new humanism.

In large part the new learning was sponsored by laymen and by the princes of Europe, who were growing in power and building brilliant courts as monuments to their prestige and authority. It is not surprising that many of the questions with which scholars concerned themselves were those of the ideal state, the model ruler, the best laws.

Politics and humanism

The humanists believed that men could improve their condition and so encouraged speculation about politics, a speculation evident even in Erasmus' writings and more obvious in those of Thomas More (c. 1478–1535) (Figure 7), Claude de Seyssei of France and Niccole Machiavelli (1469–1527). Scholars who regarded the classical past with interest and who employed new critical skills in evaluating evidence, looked to the new learning to build the future. As they adapted the models of the classics to a new and more vital vernacular literature, so they hoped to find in the past the blueprint for a better society. It was that spirit of optimism, a belief in the potential achievements of men, that gave the Renaissance its unique vitality.