European learning in the 13th century

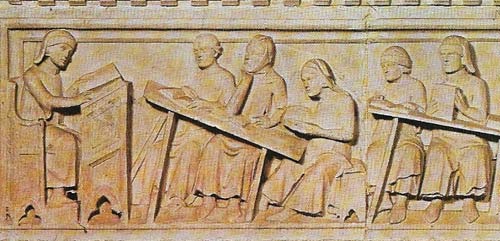

Figure 1. Cino da' Sinibaldi was a famous Tuscan lawyer and poet who died in 1336. His tomb is one of many Italian funerary monuments for academics showing the university classrooms of the later Middle Ages. The magnificence of this tomb is an indication of the importance that Italians were beginning to accord to teachers of civil law in the Italian cities. Cino had studied at the great university of Bologna and had worked at Pistola, Rome, Treviso, Florence, Siena, and Perugia. He was a link between the Scholastic academics of the 13th century and the humanist scholars who were to establish the intellectual framework for the Renaissance period from the 14th century.

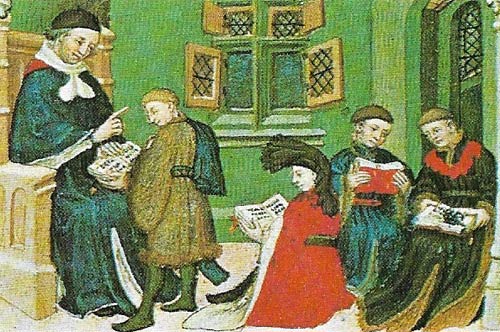

Figure 2. This 13th-century French miniature shows Aristotle teaching the Emperor Alexander as a child. The illustration is from the Treasury of Brunetto Latini (c. 1210–c. 1295), a compendium of history, philosophy and legend completed in 1265. Instruction in philosophy was thought indispensable in the training of a ruler.

Figure 3. St Bonaventure, minister-general of the Franciscan order and cardinal bishop of Albano, taught at Paris with St Thomas Aquinas. First and foremost a theologian, his most widely read work was The Journey of the Soul to God.

Figure 4. This 15th-century miniature of Roger Bacon shows him in scholarly pose. His intellectual curiosity seemed almost without limit, but the novelty of his interests and ideas led in the end to his imprisonment.

Figure 5. Bologna, one of the earliest and most famous of European universities, was noted for its law schools. The 12th century saw the emergence of student guilds which gradually became independent of the law of the city. By the 14th century, Bologna University had an organized collegiate system.

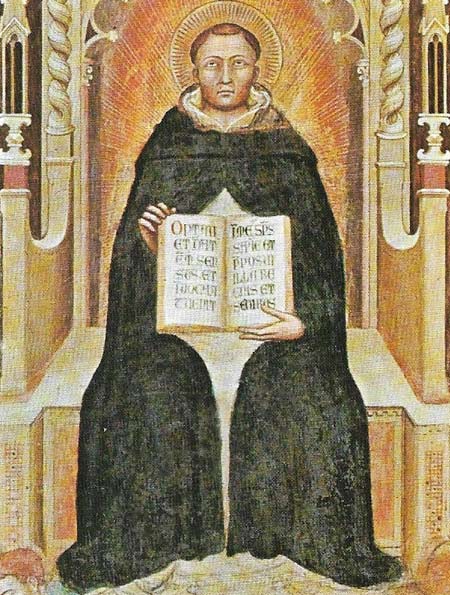

Figure 6. St Thomas Aquinas was the greatest doctor of the medieval Church and the greatest exponent of Scholasticism. His Summa Theologica, the best known philosophical treatise of his time, attempted a comprehensive synthesis of reason and revelation that established him as the Church's foremost theologian. Whereas initially his Aristotelian analysis was criticized, his statements have come to be regarded as a wholly Christian and rather overbearing interpretation of man's being and actions.

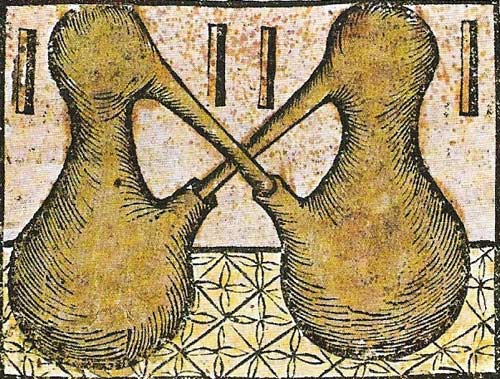

Figure 7. Alchemy was a pseudoscience of the Middle Ages. Although much effort went into improbable experiments (such as this one, which uses a double alembic) and into vain attempts to transmute base metals into gold, many alchemists were able chemists whose work laid the foundations of later knowledge. Like astrology, alchemy had its roots in classical antiquity and flourished in the 13th century along-side more fruitful scientific work on mathematics, optics and astronomy.

Figure 8. This 15th-century figure is an allegory of dialectic. Christian vices and virtues, portrayed in human form throughout medieval times, were joined in the 13th century by figures representing the disciplines of the philosophers. Dialectics, the branch of logic concerned with the rules of reasoning, was first formulated in Greece by Aristotle (384–322 BC).

The medieval papacy reached the height of its power, wealth and cohesion in the thirteenth century, at the same time as St Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274) was finishing his Summa Theologica (1266–1273), the greatest work of scholastic philosophy.

The genesis of Scholasticism

The highest achievement of medieval Christian thought, Scholasticism was an intellectual system that employed the logic, or dialectic (Figure 8), of Aristotle. In the course of the 12th century, as Aristotle's works became available to Western scholars in Latin translation, his analytic method was applied in all fields of inquiry. The result was a revolution in the methods and content of learning which produced a coherent system of philosophy and theology and a new science of jurisprudence and which laid the first fragile foundations of experimental science.

As a growing range of Greek and Arabic philosophical and scientific texts became available, centers of learning shifted away from the monasteries and episcopal schools to a new kind of academic organization – the university (Figure 1). Universities were associations or corporations of masters or students that arose in a number of urban centers where the new learning was available. The earliest of them appeared early in the thirteenth century at Bologna (Figure 5), Paris, Montpelier, Naples, Oxford, Cambridge, Toulouse, and Salamanca. Such schools gave Scholasticism its name (the teaching of the "Schoolmen").

Training at a medieval university was long and arduous. It usually took six years to become a Master of Arts, after studying logic, grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. The doctorate of theology, the highest academic achievement, required about eight more years of study.

This was the age of translation, both from the original Greek and from Arabic and Jewish texts and interpretations. Much classical cosmology, mathematics, and philosophy was revealed through the writings of Arabic scholars such as Al Farabi (died 950), Avicenna (980–1037) and Averroës (112–198). Gradually through the works of Aristotle and Ptolemy (90–168), Averroes and Avicenna, the knowledge of Greek cosmology and medicine became available, but it was above all the ideas of Aristotle (Figure 2) that influenced the thought of the early universities. Aristotelian thought was opposed to the emphasis on divine grace in early Scholastic thought and as such incurred the wrath of the conservatives. Paris in particular was the seat of new Aristotelian learning and, although the teaching of Aristotle's Metaphysics and Physics was initially banned in the schools during the thirteenth century, the prohibition was widely ignored.

Reconciling faith and reason

The crux of the Scholastic controversy was the relationship between revelation and reason. Aristotle's writings challenged the primacy of theology by asserting that rationality was the basis of knowledge, and the greatest works of this period were devoted to reconciling this apparent contradiction between faith and reason. A group of arts masters at Paris, the leader of whom was Siger de Brabant (c. 1235–1281), adopted Averroes' view that reason and philosophy were superior to faith and knowledge from faith. This provoked a fierce controversy, in the course of which Aquinas composed his famous apologia for revealed religion – the Summa contra Gentiles.

A more conservative defender of theology against the rationalist philosophers was St Bonaventure (1221–1274) (Figure 3) who conceded that some knowledge could be gained from philosophy alone without the need of faith. Like St Thomas, Bonaventure held that a philosophical proof of God's existence could be found in the need for an original cause or motion to begin the chain of events in the universe. However, he believed that philosophy could not explain the details of revelation nor could it provide a moral framework for life.

Roger Bacon's (c. 1214–1292) (Figure 4) work showed an interest in empirical observation that epitomized the growing belief in man's powers of investigation and understanding. Following the Scholastic tradition, he saw in the behavior of material things, including the commonsense behavior of man, a "natural law" that manifested divine insight. Consequently, Bacon believed that science was a natural and harmonious basis for religion. But he was also a firm believer in alchemy (Figure 7), the "science" of turning base metal into gold, and in astrology, the art of telling the future through the stars.

|

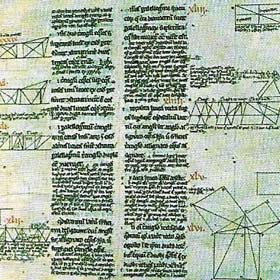

| Mathematics, like logic, played a part in the curriculum of the Scholastic philosopher, revealing through the human intellect the divine plan for the universe. Medieval mathematics consisted almost completely of a rediscovery of Greek knowledge in the field, preserved and transmitted by Islamic scholars. These Pythagorean theorems are from a 13th-century treatise which is typical of the manuals of the time. |

|

| Notations on this 13th-century manuscript of the Roman writer, Lactantius, indicate textual criticisms common to a generation aware both of the ambiguities of classical texts and the textual corruptions that had developed over the centuries. Greek and Latin works had been translated into Syriac, thence into Arabic and back into medieval Latin. Careless transcription created more inaccuracy, but greater care ushered in a new era of classical scholarship. |

The development of Aquinas' thought

Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280) incorporated the new knowledge of Aristotle within an encyclopedic formula that embraced Platonism, Neo-Platonism, and Arabic theology. Thomas Aquinas, his pupil, inherited this breadth of reference and consciously set out to provide a logical Aristotelian substructure for Christian thought. Aquinas took faith as the starting point and argued that everything discovered from reason could be interpreted in the light of it. Apparent conflict between reason and faith meant that the reasoning was wrong. He conceded that human knowledge depended on sense perception, and in his theory of "natural law" – a body of universal moral principles that can be ascertained by human reason alone – he provided the basis for a purely rational system of ethics.