Florence and Rome: the High Renaissance

Figure 1. Michelangelo’s painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel on the Vatican was commissioned by Pope Julius II, who asked Michelangelo to paint the 12 Apostles. The artist, of we believe his account, said this was a poor scheme and was given a free hand. The principal figures, on the supports of the dome, are 7 prophets and 5 sibyls, representing revelation to Jews and Gentiles. Down the center is a sequence of 9 Old Testament subjects, from the Creation (shown here) over the altar to the Drunkenness of Noah, illustrated an epoch of religious history not previously represented in the chapel. The first half was unveiled in August 1512; this second part was completed a year later.

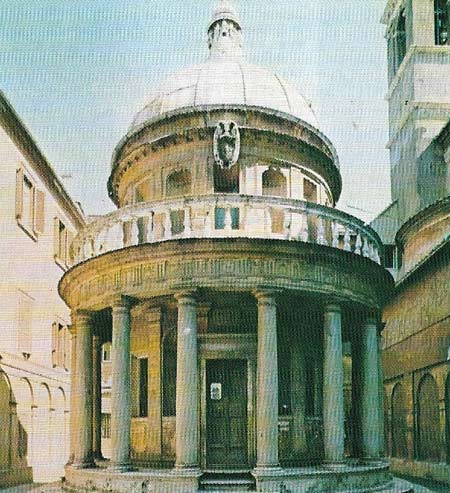

Figure 2. Bramante’s Tempietto in S. Pierrot in Montorio, Rome, was built as a shrine over the traditional site of St Peter’s martyrdom. Bramante intended that it should be tightly enclosed in a circular courtyard. The design departs from classical circular temples in its high drum with windows between colonnades and dome.

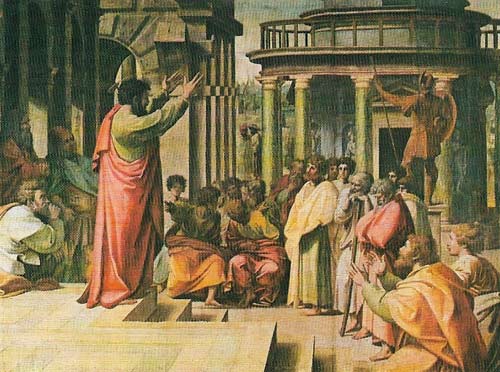

Figure 3. Raphael’s “Paul Preaching at Athens” (1515–1516) was one of a set of ten colored cartoons (of which seven survive) for tapestries, made in Brussels, with which Leo X intended to complete the decoration of the Sistine Chapel. The weaving technique required that each scene, from the lives of Saints Peter and Paul, be designed in reverse. The surviving tapestries are in the Vatican.

Figure 4. Villa Madama, Rome, was designed by Raphael in 1517 for Cardinal Giulio de Medici. This garden loggia, decorated after Raphael’s death by his pupils, particularly the brilliant decorator Giovanni da Udine, is a rare example of form, function and decoration all imitating the classical.

Figure 5. Leonardo’s “Heads of Warriors” (1503–1504) is a detailed study of the expression of the horsemen for the “Battle of Anghiari”, a mural commissioned by the Florentine republic and never completed. It is representative of the new drawing techniques that were invented by Leonardo as part of an intensive preparatory process.

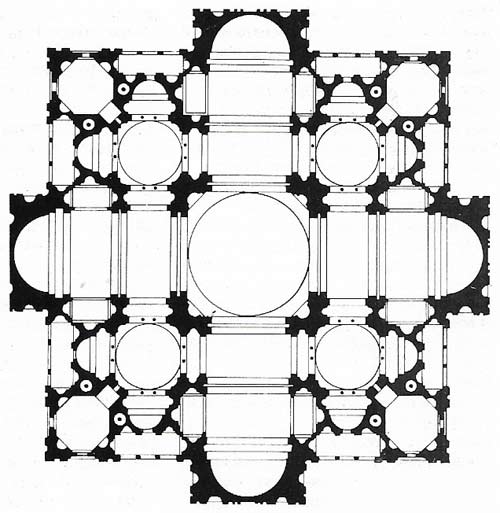

Figure 6. Bramante’s ground-plan for St Peter’s.

Historical events around 1500 seem in general once again to concentrate artistic activity in Florence, Rome, and Venice and reverse the earlier tendency to diffusion among many centers. Foreign invasions and power struggles within Italy did clearly have a disastrous effect upon patronage in courts such as Naples, Urbino and Milan. Indeed, the presence of Leonardo (1452–1519) and Bramante (1444–1514) in Milan, and the ambitious patronage of Lodovico Sforza (1451–1508), might have made that city one of the artistic capitals of Europe, but for the French conquest of 1499. Leonardo then returned to Florence, where for six vital years he and Michelangelo (1475–1564) were in direct rivalry; they were joined in 1504 by Raphael (1483–1520) (Figures 3 and 4) and successively by several younger men, notably Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530).

In Florence, too, there had been a political earthquake, but the expulsion of the Medici in 1494 and the formal revival of the republic (until 1512) in fact left a prosperous oligarchy in power and the new state institutions provided some of the greatest opportunities any Florentine artist had so far been offered, especially in the commissioning of two enormous battle-pieces from Leonardo and Michelangelo for the new council chamber (neither was finished).

Bramante and St Peter's

After 1499 Bramante went to Rome. His great opportunity came in 1506, when the energetic Julius II (pope 1503–1513) chose him as architect for New St Peter's; this building is unavoidably a symbol of the power and centralization of the spiritual Church, and for Julius its rebuilding was not so much a practical necessity as a gesture of regeneration. Bramante's plan (Figure 6) expresses these ideals with majestic clarity, and the piers of the crossing that he constructed established the colossal scale of the present building.

|

| Raphael’s painting of Pope Julius II was executed between 1511 and 1513. |

Michelangelo had already been in Rome; he returned to work for Julius, first (1506) on a projected tomb of a massive size and prolixity of sculpture undreamed of since the mausolea of antiquity, and next (1508–1512) on the painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel (Figure 1). Before the Sistine ceiling was complete Raphael had decorated for Julius the first of the suite of rooms in the Vatican Palace, the Stanze; and the Stanza della Segnatura, painted with ideal examples of the faculties of the mind, was immediately followed by his Stanza d'Eliodoro (1511–1544), decorated very differently with dramatic narratives from Church history.

|

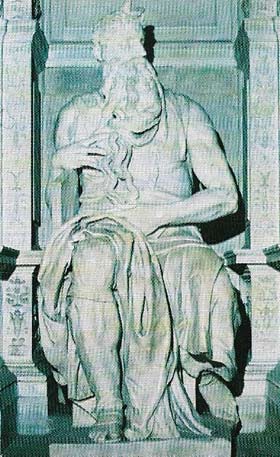

Michelangelo’s “Moses” (1513–1516), in S. Pierrot in Vincoli, Rome, was made for the tomb of Julius II. According to the second plan (1513) it was to be set fairly high up on the tomb. It’s present setting, at floor level, is in a much-reduced monument – a compromise reached, after many frustrations, during the 1540s. |

Pope Julius made Rome an artistic centre as important as Florence. He was succeeded by Leo X (pope 1513–1521), son of Lorenzo de' Medici; his taste for the arts was more personal, more refined than visionary, but many projects such as St Peter's and the decoration of the Vatican Palace and Sistine Chapel were continued. And artists enjoyed the patronage of cultivated members of the papal court and their bankers on a scarcely less lavish scale and far above 15th-century levels; this was a great period of palace building and urban redesign.

The architecture of the High Renaissance was not only Bramante's; the work of the Sangallo family is scarcely less important and Bramante's position at St Peter's, and the leadership that this almost inevitably entailed, were inherited by Raphael; Michelangelo's career as architect began about 1516. All of these, as was normal in the Renaissance, were trained in some other art and this fact is yet another cause for variety.

New intensity of feeling

A High Renaissance architectural style does exist, however: it is distinguished by total mastery, now, of the language of antiquity, by clean and measured design, by solemnity, mass and – increasingly – richness of materials. The units tend to be larger in proportion to the whole, the forms denser and more plastic than in the earlier Renaissance. and the same characteristics are found in painting and sculpture. Here, however, because figurative art offers a direct comparison with the norm of nature, the effect is, by artifice, superhuman. Figures move, with violence or deliberation, in postures that far exceed natural behavior; in their heroic and idealized forms they appear a race of supermen. This style is eloquent, rhetorical, with a new intensity of feeling.

In painting, largely through Leonardo's example, a new range of dramatic effects, of action and of physical presence of form, was made possible by descriptive discoveries about light and atmosphere and especially by powerful and unified effects of tonal contrast (chiaroscuro). In all three arts drawing had a new role (again, this was largely Leonardo's doing); the quantity of preparation in drawing was greatly increased and exploration in drawing much more conscious, and these changes express the artists' ambition towards statements that are at once more considered and more novel.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci's "Virgin and Child with Saint Anne" (c. 1510) first appeared in a cartoon (now lost) shown in Florence in 1501. The composition was slightly different from this version. |

The artist's status

The four principal artists were each personalities such as to change definitively the social position of the artist (Raphael lived in a palace designed by Bramante for a cardinal). And the maturity, the apparent perfection of their forms and the inventiveness of their compositions gave their works the status of classics. These artists earned the title Divine, hitherto reserved for poets, and their style was to be labelled the Grand Manner.