the rise of fascism

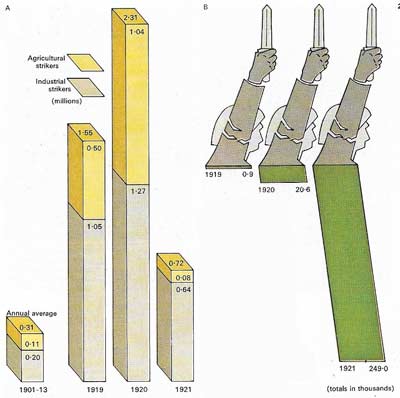

Figure 1. In 1919 Italy was crippled by war losses, inflation, and unemployment. Fascism grew in response to conservative fears of a left-wing revolution, fuelled by the mountain toll of strikes (A). Fascist membership (B) rose from under 1,000 in 1919 to 249,000 in 1921, taken mainly from the middle classes. Aided by industrialists, landowners, and the army, Mussolini took power in 1922 after a threatened coup.

Figure 2. Field-Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), a national hero of World War I, was President of the Weimar Republic from 1925.

Figure 3. The Nazis based much of their propaganda upon virulent anti-Semitism, in which the Jews were used as scapegoats for Germany's economic difficulties. The Nazis conducted boycotts of Jewish shops, attacked synagogues and assaulted individuals but were unable to adopt formal measures until Hitler's accession to power in 1933. Anti-Jewish laws promoted emigration and denied civil rights. Many Jews had left Germany or were in camps by 1939.

Figure 4. Hitler's rise to power was only half completed with his accession to the chancellorship. He awaited the opportunity to introduce emergency laws to strengthen his position and this was offered when a young Dutchman, Marinus van der Lubebe, set fire to the Reichstag on 27 February 1933. The Nazis were suspected of starting the fire, but it appears they merely took advantage of it to promulgate emergency decrees, banning rival political organizations, imprisoning opponents, and vesting power in Hitler and the Nazi Party. Although the Nazis failed to achieve a majority, they were supported by the Nationalists.

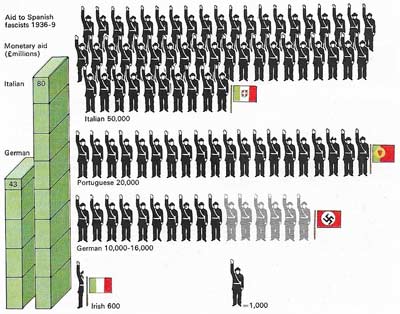

Figure 5. By 1936 both Italy and Germany were expanding their influence in international politics. The outbreak of civil war in Spain provided diplomatic and military advantages for both countries. Mussolini hoped to gain military bases in the western Mediterranean. By 1937 Italian war production was beginning to show signs of strain. Hitler hoped to sow dissension between Britain and France, while binding Italy closer to him. He used Spain as a training ground for his Air Force, including the "Condor Legion", a force of 6,500 men consisting mainly of air force units but with a few supporting ground units. From 1937 Spain became a mere sideshow.

Figure 6. Political instability in France promoted anti-Semitism particularly in magazines such as Le Cahier Jaune.

Figure 7. By 1934 Italy and Germany were ruled by fascist dictators. Mussolini (right) assumed power much earlier than Hitler (left), but the latter dominated international politics in the 1930s.

Fascism developed in the years between World Wars I and II to become a major ideological and political force in many European countries, most notably in Italy and Germany. Expressed as an intense nationalism, often with strong social and collectivist overtones, it had the support of many different groups of people in countries that were suffering from, or seemed threatened by, a total breakdown of both their economy and their society.

Fascist ideology

Although fascism shared many characteristics with reactionary nationalism and more conservative, authoritarian regimes, it had distinctive characteristics of its own. These were derived from its rejection of nineteenth century individualistic liberalism.

Fascist ideology embraced many thinkers, often distorting and misapplying their ideas. Indeed, fascism was never to formulate a clear ideology in the same way as Marxism, but remained open to a number of different interpretations, in which the component elements received varying emphasis. Among the most important contributors to fascist ideas were Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), who stressed the need for dynamic "supermen"; Henri Bergson (1859–1941), who stressed instinct above reason; and Georges Sorel (1847–1922), who emphasized the moral value of action.

Italian fascism and Mussolini

Italy emerged from World War I disappointed and frustrated by her war losses and the failure of the Versailles settlement to fulfill the treaty promises that had induced her to enter the war. Unemployment, strikes and violence (Figure 1) provided the background to the breakdown of parliamentary government. Right-wing groups, such as that led by Gabride d'Annunzio (1863–1938), seized the port of Fiume on the Adriatic coast in 1919 in defiance of the Versailles settlement. In city and countryside riots, estate seizures by the peasants and countless sit-in strikes created a menacing and unpredictable revolutionary atmosphere.

In this situation Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) (Figure 7), an ex-socialist schoolteacher, organized anti-socialist fascios to combat left-wing groups by strong-arm methods. He received support from diverse conservative elements and by 1921 there were more than 800 branches of his "black-shirts", the Fasci di combattimento. Taking advantage of the disorganization of left-wing forces, he organized a "March on Rome" which ended with his installation as premier in October 1922.

Mussolini concentrated on liquidating and terrorizing opponents, establishing the Fascist Party in power and building up his personal position. Press, courts and unions were brought under his control and he established a concordat with the Roman Catholic Church. He inaugurated public works, such as the draining of the Pontine marshes, and mounted a drive for self-sufficiency for Italy. Increasing state intervention marked Mussolini's economic policy after 1925 as he tried to create a "corporate state" in which industrialists and workers coperated for the good of the nation. Combined with his expansionist foreign policy, demonstrated both in the Abyssinian War and also his involvement in aiding Francisco Franco (1892–1975) in Spain, Mussolini's policies not only antagonized other European nations but also exhausted Italian resources.

Hitler and German fascism

In Germany the Nazis (National Socialist Party) were founded in the disillusionment and economic chaos in the years following World War I. Joined by Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) (Figure 7) in 1919, who expanded and transformed it, the party gained some seats in the Reichstag. In 1923 Hitler tried, unsuccessfully, to overthrow the Bavarian government in a putsch in Munich, for which he was imprisoned.

|

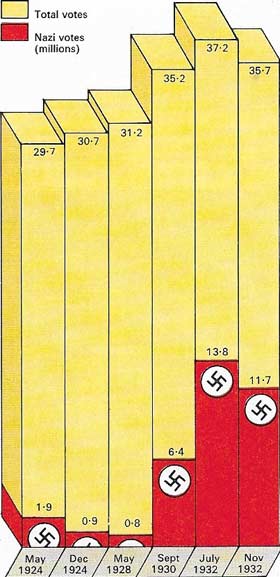

| The fluctuation in votes for the Nazis reflected the economic fortunes of the Weimar Republic. In May 1924 the Nazis gained 1.9 million votes and 32 seats in the Reichstag. With the recovery of the Weimer Republic from its postwar difficulties and the inflation of 1923, the Nazi vote declined to its lowest point in 1928 when they held only 12 seats in the Reichstag. Under the impact of a renewed depression after 1929, and with the rise in unemployment and the polarization of the middle classes, the Nazi vote rose rapidly. By 1932 the Nazis were the largest party with 13.8 million votes. Although they lost votes, Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933. |

Votes for the Nazi Party declined as the Weimar Republic recovered in the middle and late 1920s but the onset of the worst phase of the Depression after 1929 swelled party ranks with the young, the unemployed, and frightened middle-class and conservative elements. For Hitler and some of his followers, anti-Semitism (Fig 3) formed an important part of the program, the Jews being cast as scapegoats for Germany's misfortunes and as intruders in a purely Aryan Germany.

Support for the Nazis, however, seemed to have reached its peak towards the end of 1932 and the party was running into financial difficulties as funds from major industrialists dried up. In January 1933 Hitler was put into office through a coalition with the right-wing Nationalist Party, who hoped to control him. After the Reichstag fire (Figure 4), Hitler was able to assume dictatorial power. The rule of terror through the Gestapo gave the regime a more vicious character than Mussolini's in Italy. Like Mussolini's fascism, however, Nazism also offered an aggressive foreign policy and a solution to unemployment through public works and rearmament .

|

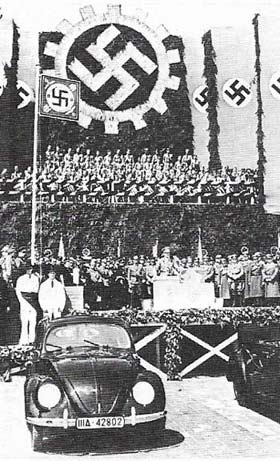

| Hitler aimed to satisfy public opinion by cutting unemployment and creating a prosperous Germany. Public works, such as the building of the autobahn network, than the most extensive in the world, provided an advertisement for the regime in reply to the criticism of its domestic and foreign critics, and also served the purposes of the military. To increase vehicle building capacity, while also providing a cheap automobile for the population, the "people's car" or Volkswagen was launched in 1938. By the late 1930s, however, living standards had begun to stagnate as arms expenditure rose. |

Fascist parties grew up in many other countries. In Spain (Figure 5), the Falange provided support for Franco, while in Eastern Europe the Romanian "Iron Guard" and the regime of Admiral Horthy in Hungary had strong fascist elements. In Western Europe the blackshirts of Oswald Mosley (1896–1980) in Britain and the Croix de Feu in France (Figure 6) appeared, temporarily, to threaten the overthrow of democratic government.