causes of World War II

Figure 1. Chancellor Dollfuss of Austria was murdered in 1934, on Hitler's orders, as the first stage of Germany's Austrian annexation. Virtual control was achieved in 1936; the take-over came in 1938.

Figure 2. The Versailles Treaty had excluded German forces from the Rhineland. In March 1936 German troops reoccupied it in defiance of France and Britain; neither was prepared to risk war to prevent this.

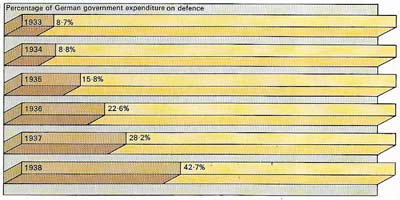

Figure 3. Expenditure on defense increased fivefold in Hitler's Germany between 1933 and 1938. Spending reached a peak in the latter stages of World War II. Germany started rearming immediately after Hitler came to power, but this drive became dominant only after 1936. Then the adoption of a four-year plan for rearmament directed more of the German economy to war than was the case in any other European country.

Figure 4. Germany's aim of absorbing German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia – the Sudetenland – almost plunged Europe into war. At Munich in 1938 Britain and France virtually sacrificed Czech industry and defense in an attempt to appease the Germans.

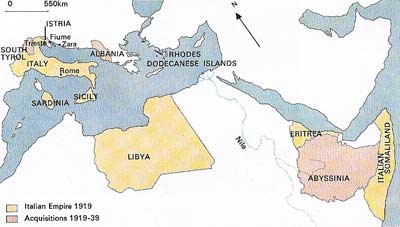

Figure 5. Mussolini's main aim from the time of his appointment in 1922 was to increase Italy's prestige and to consolidate her "Great Power" status by foreign acquisition and aggressive diplomacy. After 1922 Italy tightened her grip on Fiume, the South Tyrol and Dodecanese Islands. Protest and sanctions from the League of Nations did not prevent war with Abyssinia in 1935 and the country's rapid annexation. Italy also intervened in Spain in 1936, leading her to a closer entente with Germany, which was formalized in 1939 by the "Pact of Steel".

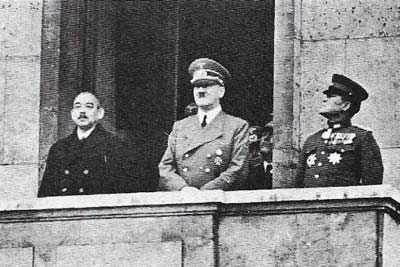

Figure 6. Matsuoka (left) the Japanese foreign minister from 1940 to 1941, was largely responsible for Japan's Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. Japan had already joined Germany in an Anti-Comintern Pact in 1936. Throughout the 1930s Japan pursued an aggressive foreign policy: in 1931 she had taken Manchuria, increasing tension in the Far East where the League of Nations was virtually powerless. In 1937 Japan went to war with a China, seizing a large area of the Chinese mainland. Europe and America failed to resolve or control the conflict, encouraging Japan to further aggression.

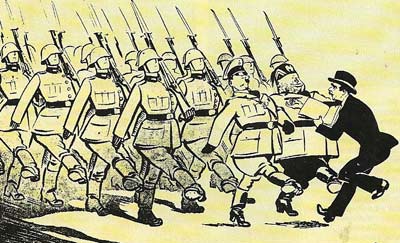

Figure 7. The appeasement policy of Britain and France arose out of fear of renewed war and believe that the dictators' demands could be met by negotiation and concession. But concern grew that such weakness just provoked more demands.

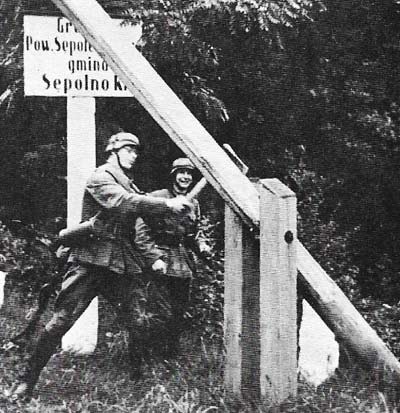

Figure 8. German troops symbolically destroyed the Polish frontier when they invaded Poland in August 1939. Polish access to the Baltic had been guaranteed by Britain and France, who therefore declared war on Germany on 3 September.

Figure 9. Hitler riding into Vienna at the head of German troops symbolizes the domination of Europe by the dictators. While Mussolini was backing Hitler in the west, Japanese economic expansion threatened the stability of the Far East.

The inter-war years in Europe saw the rise of fascist dictators (Figure 9) in Italy and Germany. Their nationalistic and expansionist policies increasingly undermined the credibility of diplomatic negotiation.

The rise of the dictators

World War I had left a bitter legacy in the crippling reparations and arbitrary divisions of territory that were features of the Treaty of Versailles (1919). Its effects were influential in the rise to power of Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) and Adolf Hitler (1889–1945). Italy had suffered losses in World War I and disappointments in the peace settlement at Versailles, and Mussolini owed a large part of his support to a policy of militant nationalism which was bound to create tensions in the postwar world (Figure 5). Hitler also gained support from a policy of extreme nationalism that was determined to reverse the penal aspects of the Versailles Treaty and unify the German-speaking peoples in eastern Europe territorially.

|

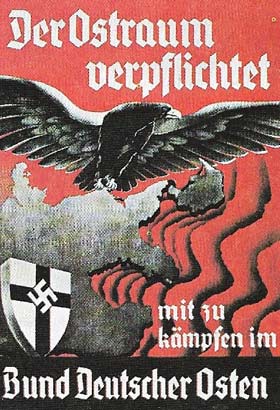

| Hitler's Mein Kampf was written while he was in prison following his abortive "Beer Hall" revolt in 1923. It contained a demand for lebensraum (living space) for the German peoples in the east. Expansion into eastern Europe and the USSR had long been a part of right-wing German thinking and Hitler adapted it as a major feature of his political policy. Its true place in his plans is much debated, but his conquests in eastern Europe by diplomacy and ultimately by war, backed by propaganda like this poster, fulfilled his professed policy. |

The isolationism of the United States meant that the major initiative for peace lay with France and Britain as the two strongest European powers. Both nations were fearful of renewed war. They felt that war in 1914 had arisen out of the diplomatic system's inability to cope with international crises, so they believed that they must negotiate with the dictators.

During the 1920s faith was placed in the League of Nations and the pursuit of policies of disarmament – policies that foundered on mutual distrust among the great European powers. By the early 1930's it was increasingly clear that the League of Nations was unlikely to act as a guarantor of peace. Japan's invasion of Manchuria and then, more seriously, the Abyssinian crisis (1935–1936) and the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) were patent indications that the League was incapable of restricting international aggression by powerful states.

A policy of appeasement

For much of the 1930s, statesmen in both France and Britain believed that Hitler's policies were designed solely to satisfy Germany's legitimate demands for revision of the Versailles settlement. In spite of Germany's reoccupation of the Rhineland in 1936 (Figure 2) and virtual control of Austria (Figure 1), Britain in particular maintained the hope that war could be averted by concession. The efforts of both Stanley Baldwin (1867–1947) and Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940) to negotiate with Hitler were supported in large part by a populace afraid of another war and resentful of expenditure on armaments in a period of economic depression. Left-wing forces in Britain were convinced that policies of disarmament must be pursued to lessen the risk of war. Chamberlain was operating from a position of weakness when Hitler was busy rearming (Figure 3). France was also beset by weakness; internal political divisions prevented a firm foreign policy and the country's losses in World War I inclined it to follow a defensive policy, enshrined in the construction of the Maginot Line.

Although Hitler's long-term aims cannot be determined with certainty, he exploited the confusion and weakness of the Western European powers to reverse the Versailles Treaty and further his plans for conquest in the east at a later date. The reoccupation of the Rhineland was followed by the Austrian Anschluss and demands for the cession of the German-speaking Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia (Fig 4). After threatening war, Hitler was placated by an agreement in 1938 that virtually dismembered Czechoslovakia in return for promises not to occupy the non-German-speaking areas of the country. Chamberlain's surrender was hailed as a triumph that had avoided war. But the occupation of Prague in March 1939 broke the illusion upon which appeasement had been based – that Hitler's demands were limited and had been satisfied.

The influence of peripheral powers

Resistance to Hitler had been confused by suspicion of the Soviet Union's intentions. Coming out of isolation in the mid-1930s, the Soviet Union was concerned to prevent an alliance of Western European states against her, but became increasingly fearful of the rise of fascism in Germany with its implied threat to herself. The USSR sought to bring the Western powers into an anti-fascist alliance, but was frustrated by the faith in appeasement and widespread mistrust of the USSR in conservative circles. The actions of Britain and France over Czechoslovakia encouraged the USSR to form a non-aggression pact with Germany in 1939.

In the Far East, the rise of a militantly aggressive Japan provided an additional strain upon the fragile peace (Figure 6). Japan's occupation of Manchuria (1931–1932) and its war with China from the mid-thirties illustrated the weakness of the League and increased Japanese self-confidence and territorial ambitions.

Britain's guarantees in 1939 to Poland and Romania were a last attempt to restrain Hitler's actions. But he had agreed with the USSR to dismember Poland on the pretext of annexing the "Polish Corridor" (Figure 8). Hitler probably expected Britain and France to back down once again as they had over Munich. Instead they presented Hitler with demands to withdraw. When the British ultimatum expired on 3 September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany, and France followed suit a few hours later.