Greek art 450 to 31 BC

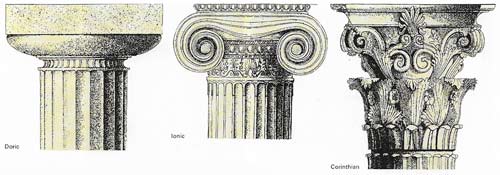

Figure 1. The three main Greek "orders" are the Doric, the earliest, whose capital has a deep abacus (the flat slab at the top) and wide-spreading echinus (the molding beneath); the Ionic, with a thinner abacus and projecting spiral scrolls with rich carvings; and the Corinthian, deeper, more elaborate and, until its adoption by the Romans, less popular the other two orders.

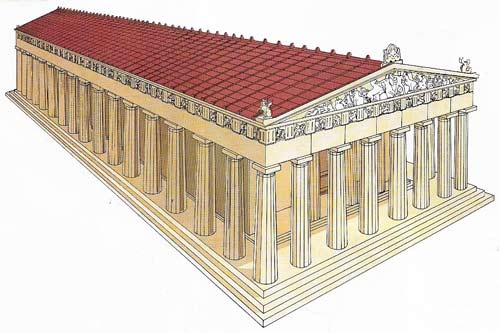

Figure 2. The Parthenon dominates the Acropolis and is one of the world's most impressive and important structures. It was erected by the Athenian ruler Pericles to replace the temple destroyed by the Persians in 480 BC. Under the overall direction of the sculptor Phidias, with Ictinus and Callicrates as architects, it took shape in the years after 447 and was completed by 438 BC, except for the sculptures, which took a further six years. Designed as an expression of Athens' supremacy and civic pride, it was Greece's largest and most costly building and a fitting center for the display of Phidias' ivory and gold statue of Athena. The Parthenon embodied many bold architectural innovations and the most cherished conceptions of the day. Entirely of the Doric order, it has 8 frontal columns instead of the usual 6 and 17 in the peristyle. The entasis or bulging effect of the columns counters the optical illusion of concavity that would otherwise occur and their slight inward leaning, coupled with the outward tilt of the upper works, calculated to the minutest degree, ensure its harmonious proportions. The frieze and metopes, which were originally richly painted, were more refined, spectacular, and skillfully executed than any predecessors and stand out among the world's greatest works of sculpture both in relief and in the round.

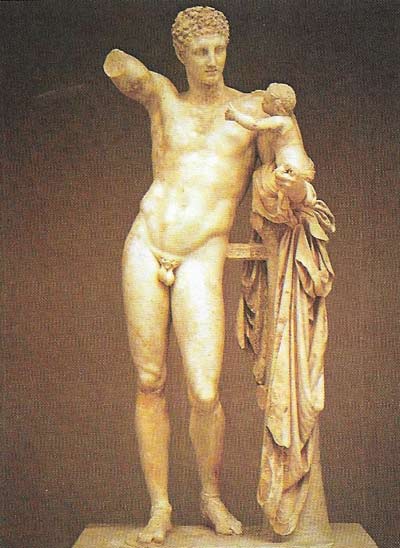

Figure 3. "Hermes carrying the infant Dionysus" is possibly the only surviving original work by the Athenian master sculptor Proxiteles, who was regarded as one of the greatest craftsmen of his age. This work displays a refinement of technique seldom encountered before the Hellenistic period. The idealized classical beauty and proportions of the figure of Hermes are enhanced by the impression of a graveful curving upward line as he playfully offers a bunch of grapes to the child-god Dionysus. This statue was discovered inside the Temple of Hera, at Olympia.

Figure 4. The "Alexander Sarcophagus" was commissioned by the last king of Sidon, who owed his position to Alexander the Great. It was both a tomb and a monument in praise of Alexander's achievements. It depicts scenes from his life, including a battle against the Persians and a spirited hunting scene. It was greatly influenced by the work of Lysippus, greatest of all fourth century sculptors, particularly in the modeling of the figures. It nevertheless conveys the vigor and dynamism with which Hellenistic art was inspired. It is also a fine example of Greek sculpture, showing traces of the original paintwork.

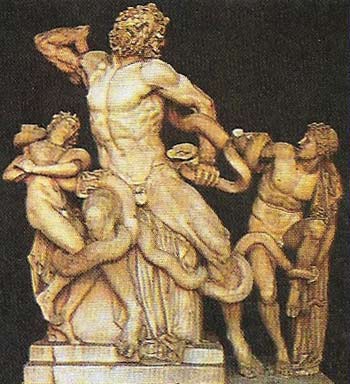

Figure 5. The famous statue depicting the death struggles of the Trojan prince Laocoon and his sons was produced in Rhodes by Greek artists who specialized in compositions conveying violence and anguish, emotions which became characteristic of Hellenistic art. Like many Greek works of the time it was much admired by the Romans and was taken to Rome by the emperor Titus in AD 69, where it was described by Pliny the Elder as "superior to anything produced in painting or sculpture". In 1506 the statue was rediscovered in the Baths of Titus and bought by Pope Julius II for the Vatican, where it was studied by such artists as Michelangelo, Bernini, and Rubens.

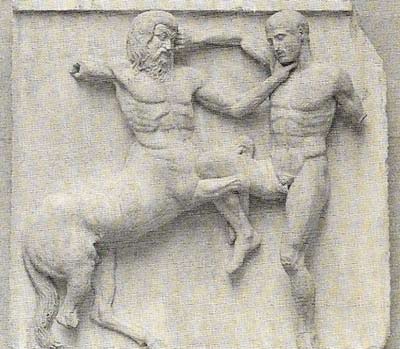

Figure 6. The theme of the friezes from the Parthenon – the fight between the Lapiths (people from Thessaly) and centaurs at the wedding of the Lappith king Pirithaus – symbolizes the triumph of order and civilization over barbarism. This was a constantly recurring motif in High Classical art.

After about 450 BC Greek art entered a phase regarded by succeeding generations as its great Classical period. It built on experience, took in new influences (especially from the East) and sought higher goals. Trends that had previously been evident, such as the concern with naturalism in sculpture. reached their peak in the work of such masters as Phidias, who is now regarded as the creator of Greek classical art.

|

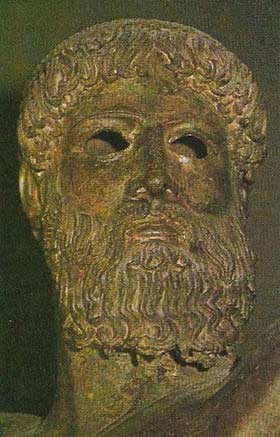

| "Poseidon of Artemisium" – a representation of one of the most revered gods of the seafaring Athenians – presents an artistic bridge between the rather stylized portrait sculpture of the earlier ages of Greek art and the naturalism of the classical era. He is among the most splendidly modeled of all surviving bronze statues with his muscular body and fine head. |

Classical formality

Yet throughout the art of the High Classical period (c. 450–400 BC), and allied with its technical virtuosity, is restraint in emotion and a lack of extremes. The art is formal, with few representations of youth or old age and virtually no depictions of anger or pleasure. The concern of the Greek sculptor for an ideal, a perfection of form, led him to a style that was serene and restrained but impersonal and cold.

The High Classical period saw the resurgence of Athens as a great artistic center, particularly under the ruler Pericles (c. 490–429 BC). After the destruction of the Persian wars, a rebuilding program of unsurpassed vision produced some of the world's most remarkable buildings – the Parthenon (Figure 2) and Erectheum on the Athenian Acropolis especially stand out for their magnificence. The sculptures of the Parthenon offer a realism and grandeur of concept unrivalled in the history of art (Fig 6). Similarly splendid architectural sculpture, reliefs. votive statues and cult figures also date from this period – Phidias' massive statue of Zeus because the Temple at Olympia was universally regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Although the heroic male figure remained the most typical, sculptors turned increasingly to representations of females, paying particular attention to draperies in, for example, Nike (the goddess of victory) figures. This shift from the idealized portrayal of the nude male to the stylized draped female is an important element in the unformalizing process which was to alter Greek art. Among other arts, wall painting is known to have flourished in the High Classical period and indeed to have taken precedence over vase painting, but material evidence is lacking. Die-engraving, especially in Sicily, was developed as a fine art.

Portraiture develops

In the Late Classical period (c. 400–323 BC), increased prosperity and patronage led to a shift from the unemotional conventions of the earlier classical period. Encouraged first by the prestige-seeking rulers of the western Persian Empire, true portraiture developed as a rival to idealized representations of divinities. Similarly, monumental tomb sculpture was introduced as a celebration of status - it is no coincidence that from this period comes the superb sculptured tomb of King Mausolus of Caria at Halicarnassus, from which the word mausoleum is derived. This work, like that of the Alexander Sarcophagus (Figure 4), was produced by Greek craftsmen working on the fringes of the empire: their work and that of mainland Greek artists – Praxiteles (Figure 3), Scopas and Lysippus in particular - mark the transition from Classical idealism to Hellenistic realism. Lysippus, for example, Alexander the Great's official sculptor, produced works that, unlike some formal groups of earlier Classical times, could be viewed satisfactorily from virtually any angle. He also produced lifelike portraits of the patron. In response to the newfound wealth of the Greek Empire, both painting and jewelry flourished.

Realism in the Hellenistic period

The Hellenistic period (from the death of Alexander in 323 to the Battle of Actium in 31 BC) was the last phase in the history of Greek art. The development of court life stimulated a wide range of arts; Pergamon was established as a leading center of architecture and sculpture, while distinctive local schools emerged in the Seleucid Empire and in Alexandria and Rhodes. Athens alone preserved many of the traditions of classical art and continued as the primary center on the Greek mainland.

The aspirations of the rulers of the Alexandrian Empire led to a greater emphasis on portraiture, which often attempted to, convey the quasi-divine status of its subjects. For the first time, representations of men predominated over those of gods and the original religious and mythological flavor of Greek art declined and was replaced by accurate – if still sometimes idealized – depictions of notable people. Both public and domestic architecture became increasingly grand while large-scale temple building declined. The more elaborate Ionic order was generally adopted in preference to the austere Doric, and the Corinthian order was used for the first time in exterior construction (Figure 1).

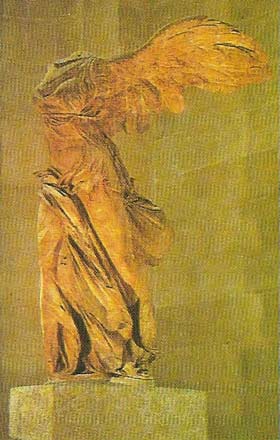

Works of sculpture such as the reliefs from the altar of Zeus, Pergamon, the Nike of Samothrace and the Laocoön group depicted vigorous action and emotion (6); femininity was portrayed in such works as the Venus of Milo; while physical suffering, anguish, old age and extreme youth were represented for the first time.

|

| The Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace – an example of the superb work of the Rhodes school of sculpture from the Hellenistic period – was probably made to commemorate a sea victory over Antiochus III of Syria and originally depicted Victory alighting on a ship's prow. The powerful, yet light movement of the figure is expressed by the swirling garment. |

Towards the end of the Hellenistic period, a trend to the copying of earlier, classical works can be observed. Through this process and the Romans' large-scale absorption of its chief elements, the continuity of Greek art was assured.