India in the 19th century

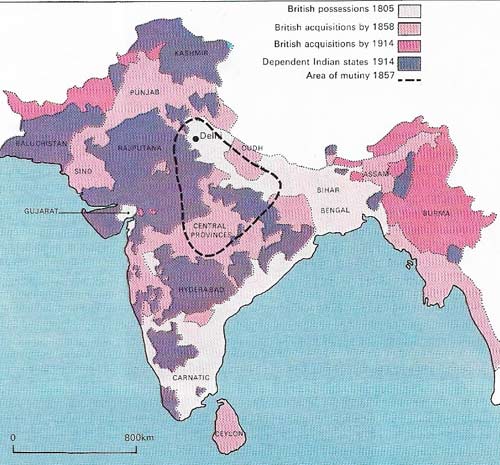

Figure 1. British control of India developed from modest beginnings on small coastal trading stations into an empire that made Britain one of the greatest powers in Asia. Apart from direct administration of the great provinces Britain supervised nearly 600 princely states which were allowed wide autonomy but were carefully prevented from befriending imperial rivals or threatening the basic authority of the British.

Figure 2. Indian opium was bought by the British in exchange for manufactures and sold in China for silks, spices and tea demanded by British consumers.

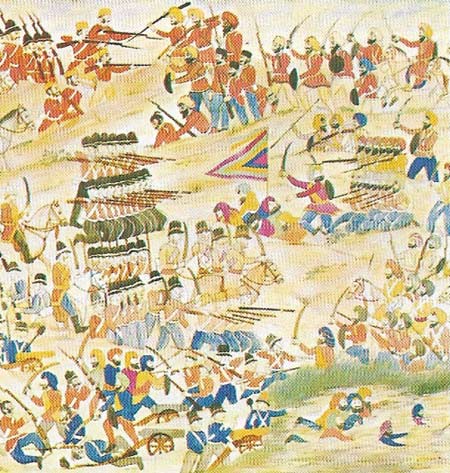

Figure 3. The Indian Mutiny of 1857–1858 was marked by several fierce battles before British reinforcements arrived and suppressed the sepoys. Although the rising failed from a lack of concerted leadership it took Britain completely by surprise and left a legacy of distrust as well as denting the complacency of British attitudes towards the Indians.

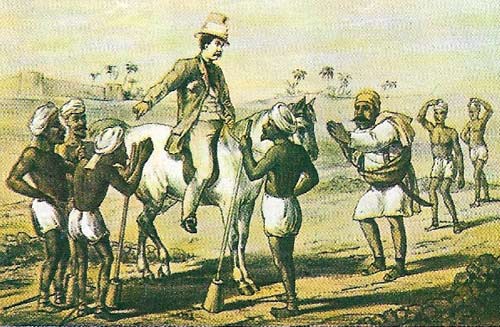

Figure 4. A British magistrate on tour represented a focal point of authority. Great value was attached to keeping in touch with local headmen and other important Indians in rural districts.

Figure 5. British and Indian troops on the Northwest Frontier were deployed in large numbers in attempts to check the historical incursions of mountain tribesmen into the plains of northern India. When the British became rulers of India they were determined to subdue the unruly hill men. They also feared that their great rivals in Central Asia, the Russians, would try to undermine their power in India using Afghanistan as an ally. Desperate rearguard actions, such as that depicted in W. B. Wollen's painting "Last Stand of the 44th Foot at Gandamuk", followed some Afghan campaigns.

Figure 6. Simla became the summer capital of the British central administration in India after 1864. Lying in the Himalayan foothills, its bracing climate was a relief from the heat of the plains. It became a resort where British administrators, army officers and their families, isolated in their districts for most of the year, could enjoy a wider (and sometimes disreputable) social life. The hilly site became a status key: senior officials lived higher up.

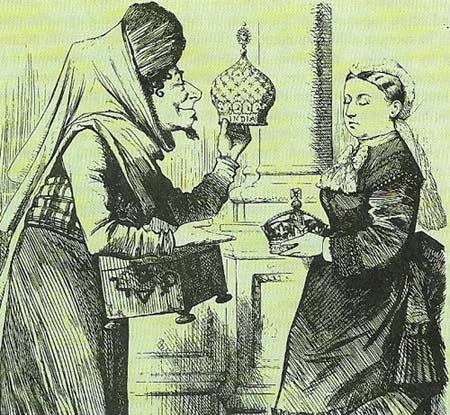

Figure 7. Stable British rule in India underlined when Queen Victoria became Empress of India in 1876, at Benjamin Disraeli's suggestion. The event was depicted in a contemporary cartoon.

By the end of the 19th century most Englishmen regarded India as being as indissolubly linked to Britain as Yorkshire or Wales. The idea of an independent India was so remote as to be almost unimaginable. The creation of the great Indian Empire was largely accomplished between 1800 and 1860 and many Victorians saw it as Britain's supreme achievement, an essential part of Britain's rise to world power.

British territorial conquests

After 1800 the British deliberately set about enlarging the territorial conquests that Clive had begun in the mid-18th century (Figure 1). By 1820 they had greatly expanded their holdings in south India and secured their position against the revival of native princes such as Tipu Sultan. In the north of India the same process was carried on more slowly, but no less relentlessly, culminating in the conquest of the Punjab from the Sikhs in 1849 and the annexation of Oudh in 1856.

|

| Tipu Sahib, Sultan of Mysore, was and aggressive, expansionist ruler who was a thorn in the side of the British in south India, even allying himself with Napoleon. He died fighting the British in 1799. |

These great conquests were not inspired by simple avarice. They seemed to follow logically from the efforts of the East India Company (which was the instrument of British power in India until the British government's takeover in 1858) to protect itself against the threats to its trade. For with the decay of the Mogul Empire new states arose more unstable and less friendly to the company, forcing it to rely not on diplomacy but on its own armed strength. Once this process began it was difficult to stop. Raising armies in India required the company to control more land and more people, and to extract more revenue, the main source of which was the tribute traditionally paid by cultivators to their ruler. Thus each new war led to new annexations of land to pay for the company's armies and to ensure that the defeated rajahs and nawabs would not have another opportunity to attack.

Once India was fully under their control the British used its resources, and above all its army (paid for by the Indian taxpayer), for their own wider purposes in Asia, compelling the Chinese to open their ports to British trade (Figure 2). Possession of India became indispensable to Britain's position as a great power east of Suez. But in India itself the British had to devise a system that would enable them to govern its vast area and huge population efficiently and cheaply. It was a novel problem: nowhere else had they attempted to rule people so different in language, culture and religion. And it had to be accomplished using only a very small number of British administrators (Figure 4).

The result was that for all the appearance of despotic power the British relied upon the cooperation of Indians: village administration was largely delegated to lesser Indian officials while the good will of rural notables – upon whom fell the main burden of keeping order in the countryside – was vital. This meant turning a blind eye to minor irregularities and preserving, where possible, the existing structure of local power.

Indian Mutiny: causes and effects

The extension of British control was not accomplished without violent reaction on the part of their Indian subjects, most notably in the mutiny of 1857–1858 (Figure 3). Although the mutiny arose initially from the refusal of Indian sepoys (soldiers) to bite open cartridges greased with animal fats forbidden to Muslims and Hindus, it swiftly became a much wider rebellion against the side-effects of company dominance: heavier taxation, displacement of Indian magnates from positions of authority and the introduction of laws that abruptly altered the old systems of landholding, rent-paying and tenancy.

For a time British authority all over north and central India swayed in the balance; Lucknow was overrun and Cawnpore besieged. The British restored their authority through the deployment of a large army, the systematic destruction of the hostile sepoy forces and savage punishment for those they considered rebels. But they learned their lesson. They realized that the mutiny had resulted from too rough a handling of the Indian gentry, from the anxieties that too much rapid change had aroused in the Indian population and from Indian fears that the British were planning to attack religious cus-toms and practices.

After the mutiny the British were more careful and administration by the company was replaced by government rule. Headlong changes in law and in the economic character of rural life through new systems of taxation were slowed down or stopped altogether. The wholesale demolition of the remaining princely states was halted and the rajahs and princes were promised security in return for their swearing allegiance to Queen Victoria.

|

| Indian economic life continued largely unchanged in villages during British rule. Better communications, however, did help to combat the scourge of famine and to stimulate the growth of large cities such as Calcutta and Bombay. |

Stirrings of independence

By the later 19th century the whole spirit of British rule in India had changed. The British gave up the hope that social change and education would quickly and smoothly turn Indians into "brown Englishmen" and India into a modern society. Administrators concentrated on keeping the status quo so as not to risk their power. This could not work for long. India had been opened up to the outside world and flooded with British goods and British ideas. In the big towns, economic change produced Westernized Indians who wanted a say in government. In 1885 men such as these founded the Indian National Congress and in doing so began, unwittingly, the long struggle for independence.

|

| Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India 1898 to 1905, symbolized the pomp and circumstance of British rule. Although an untiring administrator he found the task of governing India frustrating and his autocratic ways were resented. |

,are,,,

,are,,,