imperialism in the 19th century

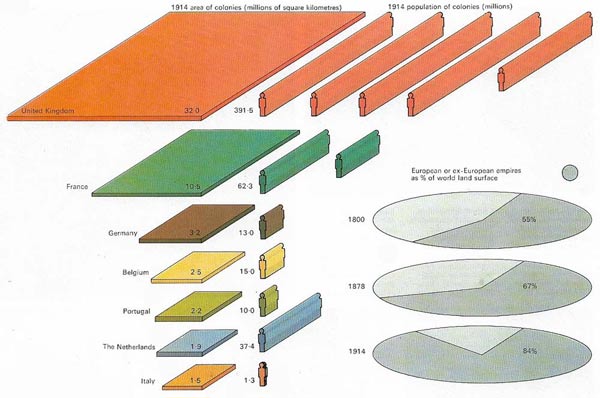

Figure 1. The colonial empires of the European powers were rapidly extended between 1800 and 1914. The British Empire, already with a huge possessions, expanded in Africa and South-East Asia; France and Germany acquired big territories and Belgium, Italy, Portugal and The Netherlands also joined the scramble. Including the ex-colonies in America, European influence extended to 84 per cent of the world's land area by 1914.

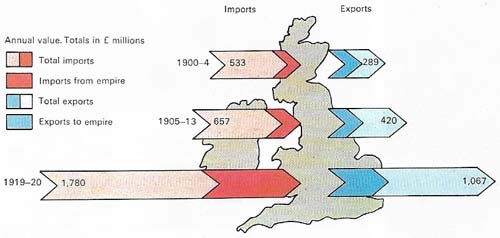

Figure 2. As trading partners colonies were usually more important suppliers of raw materials and food than buyers of imperial goods. Some of the territories acquired after 1870 hardly repaid the cost of running them. But Britain's "white" colonies were significant investment outlets and trading partners, particularly after 1900 when the volume of two-way imperial trade rose to more than one-third of Britain's total visible trade.

Figure 3. National rivalries for overseas territories, such as depicted in this cartoon of Britain, Germany, Russia, France, and Japan dividing China, were often fanned by attitudes at home. In the 1870s the word "jingoism" was coined to describe a belligerent attitude fostered by the rise of mass-circulation papers. British disputes with Russia on the North-West Frontier on India and with France over Sudan in 1898 led to popular support for war, although ultimately it was averted.

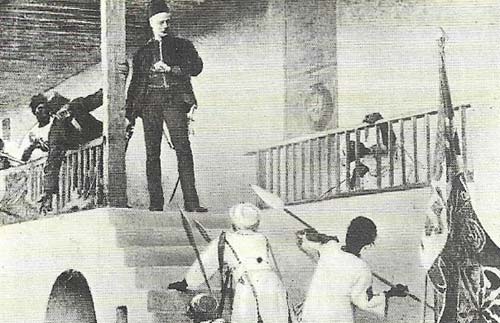

Figure 4. The death of Charles Gordon (1833–1885), a British general, at the hands of Sudanese religious fanatics in Khartoum led to public outrage in England against governmental bungling. Gordon's bravery epitomised the romantic appeal of imperialism, which was seen as providing an outlet for heroism and adventure in exotic parts of the world, whether in seeking new colonies or in garrisoning and protecting existing ones.

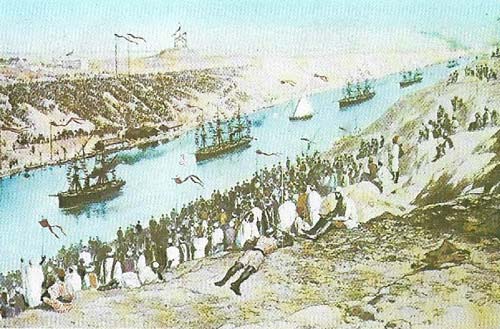

Figure 5. The Suez Canal provided Britain with a reason to add Egypt to its empire in 1882. Constructed by a Frenchman, Ferdinand de Lesseps, the canal was opened on 1869, making a short route from Europe to India. Britain acquired the canal shares in 1875, following the bankruptcy of the Egyptian khedive. A nationalist revolt prompted Britain to intervene and take Egypt under effective control to safeguard the canal.

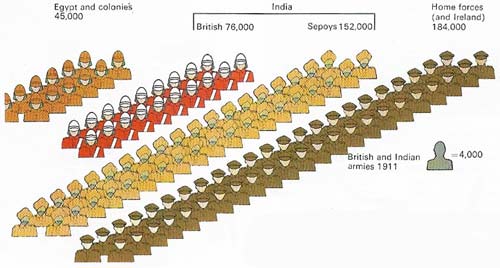

Figure 6. Imperial garrisons (some in Ireland) accounted for the bulk of the British regular army in 1911. In India, local sepoy troops contributed to British power.

Figure 7. European supremacy overseas was symbolized by Queen Victoria when she became Empress of India. The greatest imperial expansion of the 19th century, however, took place in Africa.

The nineteenth century saw a major expansion in European control and influence over the rest of the world. Earlier, important empires had existed in the ancient world and the Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese had established extensive trading empires in the 16th and 17th centuries. But the nineteenth century was the period of Europe's greatest overseas expansion when European influence was introduced for the first time to a wide variety of races and peoples (Figure 7). By 1914, more than 500 million people lived under imperial rule (Figure 1).

The rise of Britain

In the course of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the older empires of Spain, Portugal, and Holland entered a decline. A series of revolts freed the Latin American republics from Spanish domination and virtually ended the economic importance of the Spanish Empire. After a sequence of wars in the eighteenth century, culminating in 1815 with the defeat of Napoleonic France, Britain emerged as the strongest maritime nation with substantial colonies and many island possessions.

During the middle years of the 19th century, colonial expansion was relatively limited; Britain concentrated on consolidating her hold upon the colonies she already possessed, partly by conceding self-government to the most developed and responsible, such as Canada, and also by military force (Figure 6), as in the suppression of the Indian Mutiny of 1857–1878. During this period Britain pursued a policy of "informal control", attempting to limit her commitments to those essential to the maintenance of trade, while avoiding large-scale involvements in governing new territories. Thus characteristic British acquisitions of the mid-nineteenth century were positions of strategic or commercial significance, such as trading rights in Singapore, purchased in 1819 from the sultan of Johore, and trade settlements on the African Gold Coast, bought from Denmark in 1850. The British attitude to India was somewhat anomalous. Although many Englishmen were prepared to contemplate the eventual secession of most of her white colonies, the prospect of India's becoming independent was never actively supported. After the suppression of the Indian Mutiny, the maintenance of India as a vital part of Britain's overseas interests became the lynchpin of imperial policy.

The scramble for Africa

By 1870, there were stirrings in several parts of the world that had remained beyond European influence. Africa was being opened by the journeys of the great missionaries and explorers. Technological developments in weaponry and transport and advances in tropical medicine made it easier to penetrate the "dark continent". Once explorers had charted the routes it was inevitable that further European involvement in Africa would follow. The "scramble for Africa" began when, mainly for strategic reasons of safeguarding the main route to India, Great Britain occupied Egypt in 1882 (Figure 5). Within 20 years almost the whole continent had been divided up between the major powers. Economic incentives, strategic concerns, and diplomatic rivalry all played a part in the expansion of European influence. However, the degree to which economic motivation accounts for the rapid expansion of the European empires between 1870 and 1914 has often been overstated. In contrast to the earlier phase of European colonialism, trade (Figure 2) now tended to follow the flag rather than act as a direct cause of territorial annexation.

Strategic and political considerations

In 1865, a British Parliamentary Committee was prepared to concede influence in the economically important area of West Africa in favor of strategic benefits in the economically poorer East Africa, with its ports on the Indian Ocean. In France, colonial development was largely a preoccupation of the government, a minority of businessmen, the military, and exploration groups, with little active support from the electorate. Similarly in Germany, Bismarck pursued a colonial policy for diplomatic and internal political reasons. As a result, the new territories acquired after 1870 tended to take only a limited part of the export of European capital and population, and provided a relatively small volume of trade, supplying mainly tropical products such as rubber, cocoa, and hardwoods.

|

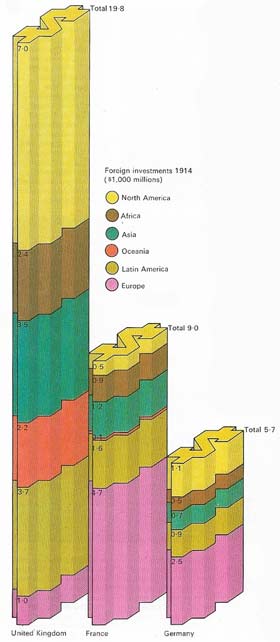

| The growth of European investment overseas was a major aspect of imperialism after 1870. The most important exporters of capital were Britain, France, and Germany. By 1914 they had invested over US 30,000 million dollars in foreign and colonial loans throughout the world. Although some commentators, such as Lenin, saw the search for markets and investment areas as a primary motive for imperial expansion, relatively little European capital went to territories acquired in the period of greatest expansion between 1870 and 1914. France and Germany invested most of their capital outside their colonies, especially in eastern Europe. Half of Britain's overseas capital went to the empire, but it was invested mainly in the "old" empire of the white colonies and India, where it brought in a large revenue which helped pay for Britain's imports of raw materials and food. |

Although the new imperialism was motivated primarily by political and strategic imperatives, it was fostered by a climate of approval for the "civilizing mission" of the European races. The benefits of trade, Christianity and European rule were considered obvious by many educated people in the imperial nations, providing powerful self-justification for the extension of colonial rule over "primitive" peoples. By the late 19th century, the glamor of imperial adventure (Figure 4) was taken up by the emerging mass-circulation press to foster "jingoism" and bring pressure to bear on politicians to support aggressive imperialism (Figure 3). But until 1914, in spite of periods of acute tension and rivalry, the partition of Africa and expansion elsewhere was conducted without a major conflict between the European powers. A series of agreements and treaties defined areas of control and spheres of influence, leaving Great Britain with the largest overseas empire, followed in size by those of France and Germany.