The Industrial Revolution

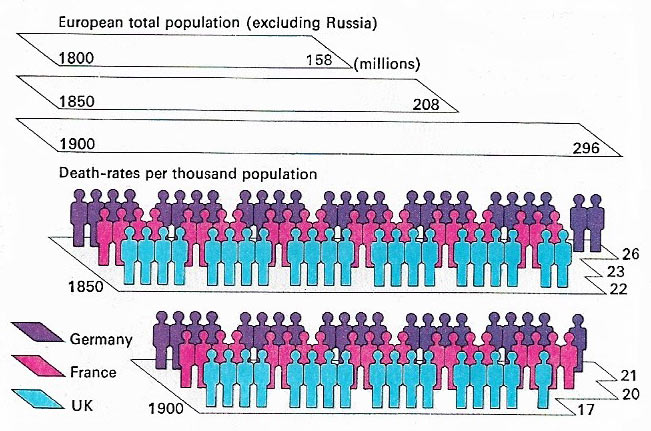

Figure 1. Europe's population rose steadily during the 19th century, mainly because of a falling death rate through improvements in medicine, diet and living conditions. Birth rates also tended to rise with industrialization and urbanization. As a result, the total population of Europe almost doubled in the course of the century, quickening migration from the countryside to the increasingly crowded urban centers.

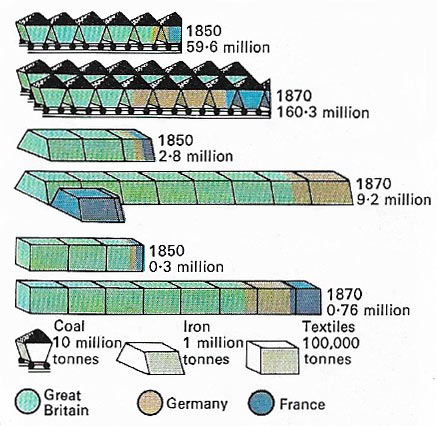

Figure 2. Industrial output was rising in many parts of Europe by the middle of the 19th century. Germany and France began to take a significant share in producing iron, coal, and textiles and smaller countries such as Belgium and Switzerland were also beginning to develop important industrial sectors. European industrialization still lagged behind that of Britain and was inhibited to some extent by Britain's marketing dominance.

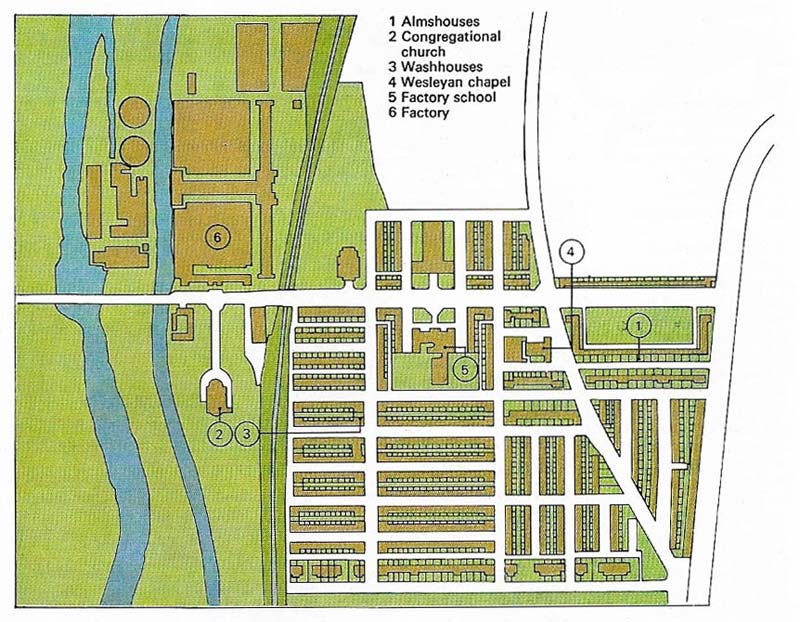

Figure 3. New industrial towns, such as Saltaire, in Yorkshire, England, provided shelter and adequate living conditions for large numbers of workers. By the middle of the 19th century factory owners and municipal authorities began to create some order out of the squalor of early factory towns. Regular grid-iron patterns of workers' housing were built, providing the basic amenities of sanitation and water.

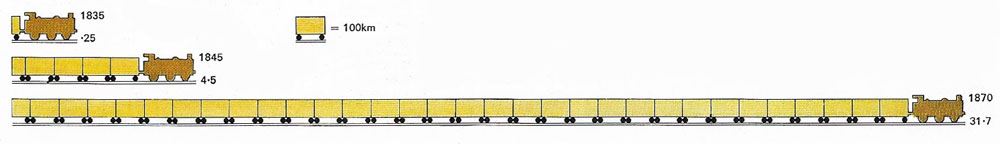

Figure 4. Railway expansion in Belgium between 1835 and 1870 was typical of the rapid developments that took place in Europe in the middle and late nineteenth century. British engineers, contractors and equipment were often employed in an effort to overtake the British lead. Although railways developed more slowly on the Continent, Britain had opened a major trunk route system for carrying goods and people by 1847. The diagram represents length of rail track laid.

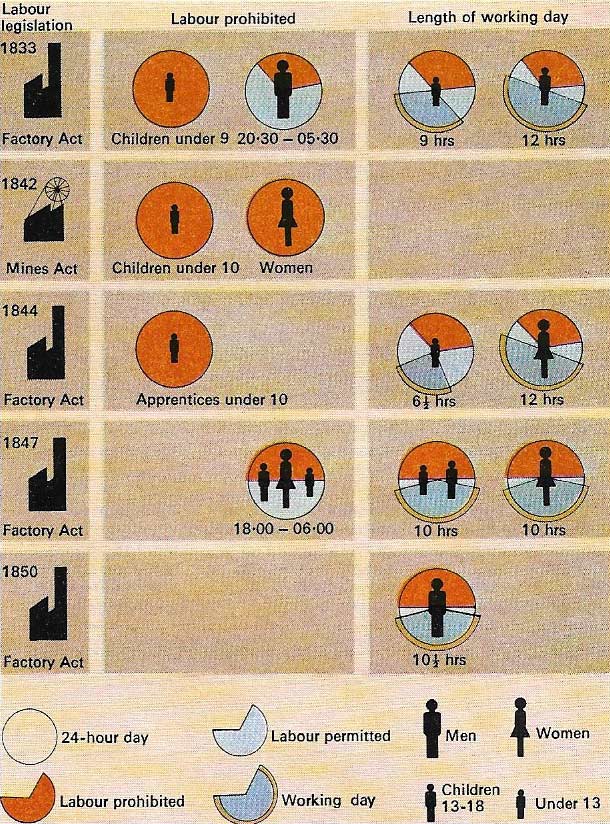

Figure 5. Exploitation of child and female labor, with long hours, low wages and poor conditions, was a major abuse of the Industrial Revolution. In the middle of the 19th century, humanitarian concern in Britain led to the passing of Factory Acts to protect women and children.

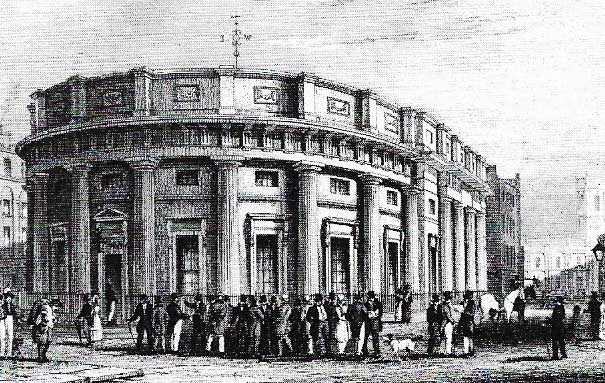

Figure 6. The Cotton Exchange in Manchester was one of a number of major commercial institutions set up throughout Britain to deal in particular commodities. The growth of large-scale industry and the demands of a more complex society forced rapid developments in finance and banking. The Stock Exchange, which had become the center for financial dealings, continued to expand, doubling in size during the 1860s alone.

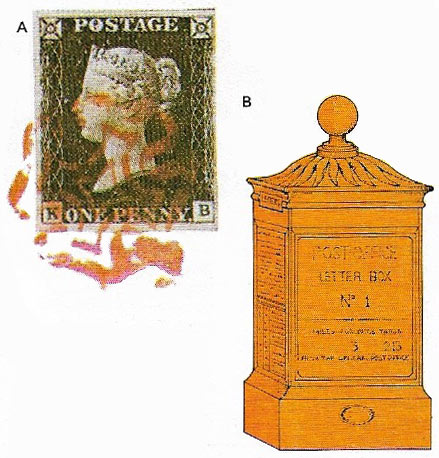

Figure 7. A cheap postal system was one of the many new social amenities made possible by growing community wealth and a more ordered urban society. In Britain, the railway system permitted rapid movement of mail and a "penny post" was introduced by Rowland Hill in 1840 (A). The British Post Office introduced the first of its distinctive red letter boxes in London in 1855 (B). A telegraph system came into use in the middle of the century, with undersea cables providing the first international means of communication. By 1861, 18,000 kilometers (12,250 miles) of cable had been laid.

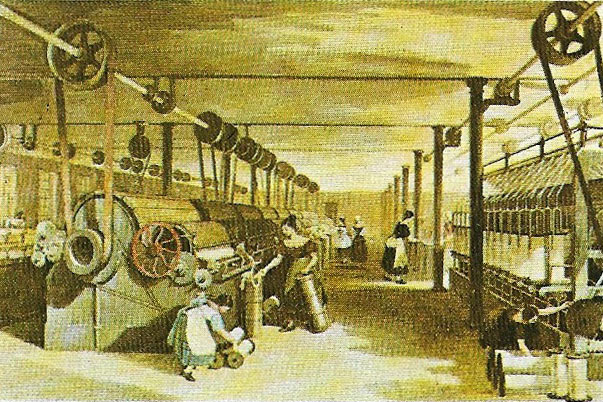

Figure 8. The cotton mill was the symbol of the 19th-century industrial town. Cotton was the most completely industrialized sector of the economy, being almost entirely mechanized, steam-powered and factory-based, and was one of the first industries to develop in Europe. Mills were gaunt, utilitarian structures, housing long banks of spinning and weaving machines, tended largely by women and children. Conditions were often dangerous with many accidents; hours were long, even for very young children, and discipline was strict. In Britain by 1851 over half of the population lived in urban rather than rural areas. Factory conditions improved only slowly.

The first 70 years of the 19th century saw unprecedented economic development in Britain as forces unleashed at the end of the 18th century created the first urban industrial society. Population growth and urban development followed an acceleration of industrialization based on a great expansion of trade, the widespread application of the factory system to production and the harnessing of steam-driven machinery to an increasing range of processes. Steam power was also applied to transport with the development of railways and the first steamships. Urban life prompted Britain to develop many social and political institutions that were to become standard in other countries as the Industrial Revolution spread to Europe and the United States.

The British lead

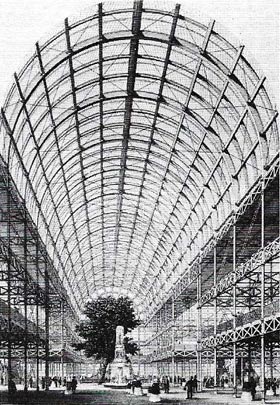

Britain's economic development between 1800 and 1870 was startling, even compared with the progress of the late eighteenth century. There were giant increases in production. Output of pig iron grew 60 times, coal output ten times and total trade by the same amount. Britain maintained and increased her lead over other countries by advances in mechanization and factory production. In a real sense Britain had become the "workshop of the world" by the time of the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851 when great industrial expertise was on display.

|

| The Great Exhibition of 1851, in London, marked a high point in Victorian industrialization. Organized to show the progress in trade and manufactures achieved since the first days of the Industrial Revolution, it became a symbol of British manufacturing ingenuity and dominance of world trade, although it exhibited industrial goods from many other countries. It was intended to display the virtues of free trade (laissez-faire) as an agent of economic progress. To house it, a revolutionary building of glass and iron was designed by Joseph Paxton and built in only seven months. The Royal Society of Arts sponsored the exhibition with the backing of Albert, the Prince Consort. |

Britain supplied a large percentage of the world's textiles, iron and machinery, and a massive increase in her export income was stimulated by the development of "free trade", especially during the 1841–1846 ministry of Robert Peel (1788–1850). After 1850 trade expanded even more rapidly than it had in the first half of the century, encouraging further economic development. New industries such as steel (based partly upon the newly discovered Bessemer process) and shipbuilding began to balance Britain's dependence on exports of textiles (Figur 8) and iron products.

The development of railways after the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825 gave a major boost to the economy, making it possible to move bulky goods cheaply and stimulating the iron and steel industries. The railways served to concentrate production still further, as raw materials could be brought long distances and finished goods sent to ports many miles away. During the boom years of "railway mania" in 1845–1847 a basic railway network covering the major towns, industrial areas and ports had been laid out by railway pioneers such as George Stephenson, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, George Hudson, and Thomas Brassey. In addition, the development of railways played an important part in refining investment and banking procedures.

Financial organization

As the pace of industrial expansion quickened, the need arose for a more elaborate banking system. In Britain the less reliable "country" banks were more and more superseded by "joint-stock" banks after 1826. The Bank Charter Act of 1844 secured the role of the Bank of England as the central note-issuing authority and guarantor of the rest of the banking system. Company finance and formation were regulated by a series of limited liability and company acts in the middle of the nineteenth century. The growth of trade led to the expansion of the Stock Exchange and the rise of provincial exchanges (Figure 6) to deal in specific commodities. By 1870 Britain was not only the center of the world's industry and trade but its financial capital. Personal wealth increased rapidly.

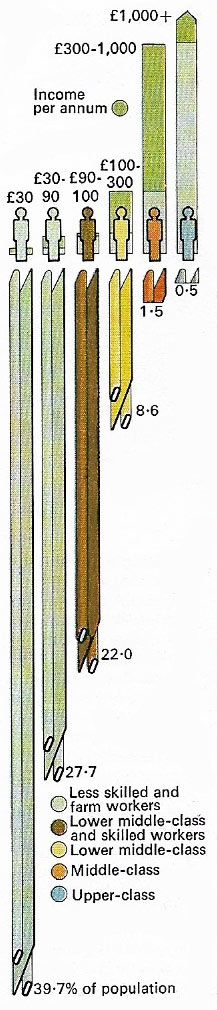

|

| Incomes and social status in Britain changed with the rise of the middle and professional classes and the creation of a new class of manufacturers. But in the middle 19th century the largest group still earned less than £30 a year. |

Population growth

Economic and industrial development was accompanied throughout Europe by population growth (Figure 1). Britain's population increased most rapidly of all, doubling between 1801 and 1851. By the middle of the century Britain was no longer a predominantly rural nation, for more than half its people lived in towns (Fig 3). In 1801 there were only 14 European towns with more than 100,000 inhabitants, but by 1870 there were more than 100.

Urban development brought with it a wide range of social and political problems. To deal with these Britain, as the first industrial nation, pioneered many social institutions fundamental to modern life. Measures to regulate public health, provide basic sanitary and housing amenities and preserve public order through the formation of professional police (the "Peelers") were copied by other countries. Similarly, the introduction of a reliable, cheap postal service (Figure 7), the rise of cheap newspapers and the development of cheap railway travel dis something to offset the human misery that often accompanied urban development and industrial advance.

Factory Acts (6) regulated child and female labour, as well as hours of work, from the 1830s. Under early pioneers such as Robert Owen (1771–1858) and Robert Applegarth, industrial workers began to organise themselves into trade unions, political associations and the cooperative movement, in order to improve their status.

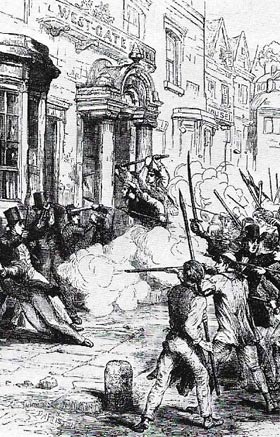

|

| Riots and strikes in England during the 1840s accompanied efforts by the Chartist movement to win urban workers the vote. Industrialization brought many such political movements and played a part in the European revolutions of 1848. |

In Europe the gathering pace of industrial development was shown in the growth of railways (Figure 4), textile industries and iron and coal production (Figure 2) by 1870. Belgium, France and Germany made the largest strides, and although far behind Britain, both Germany and the United States were poised for rapid industrial development in the latter years of the nineteenth century.