political thought in the 19th century

Figure 1. Appalling social conditions existed in 19th century Europe as a result of the development and concentration of industry and a boom in population. By 1848 the "social question" was causing concern. Neither government nor individuals did much to tackle the problem. Chartism emerged as a force in Britain, while in Europe the old spirit of revolution was again showing signs of revival. But in the long term, a steady if slow increase in living standards was brought about not by political organization and agitation, as might be supposed, but by the unexpected growth of the economy.

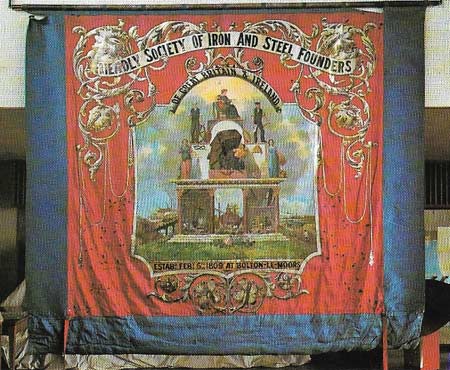

Figure 2. The world's first trade unions were founded in Britain where they were legalized in 1825. This was well in advance of other countries - trade unions were first tolerated in France in 1864 but not made legal until 1884, while Germany did not permit them until the 1890s. Membership of the early British unions such as the Friendly Society of Iron and Steel Founders was restricted to local skilled artisans. The first large union was the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, founded in 1851, but it had more interest in social benefits than in trade disputes. By 1875 unions were well established and the laws on strikes, picketing and contractual obligations had been clarified.

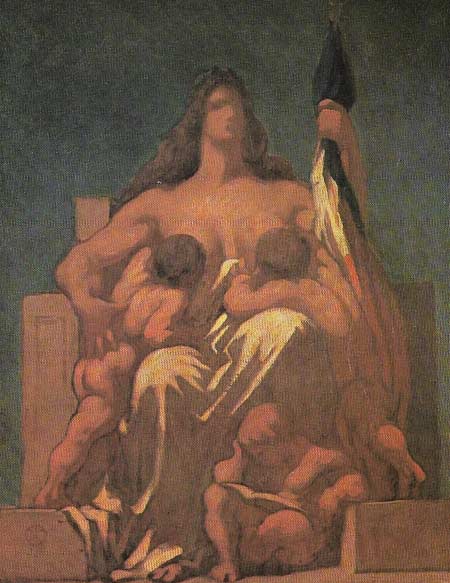

Figure 3. "The Republic", a symbolic painting by Daumier (1808–1879), shows the idealism often attributed to such government. Before the French Revolution republics were considered as legitimate as any monarchy but after 1815 they went "out of fashion" and Europe grew more monarchical. As new states such as Belgium, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria were created, so too were new monarchies. Although monarchy was no longer divine it was the system of government most comprehensible to the ordinary man. It was argued that only monarchy could unite all groups and all classes. Even France was little different. It was ruled by kings or emperors for most of the century and the Third Republic was established by one vote in 1875 as the regime that "divided Frenchmen least".

Figure 4. The Geneva Convention of 1864 established the International Red Cross. This was a humane reaction to the suffering of soldiers in the wars of the 1850s but also concern about problems of war itself. Other aspects of this were the continuing attempts to regulate war by law and the strength of the international pacifist movements. Peace congresses were held frequently from the middle of the century onwards. By 1900 there was a belief current in Europe that some genuine progress had been made towards achieving permanent peace.

Figure 5. Napoleon's statue was overturned in 1871 to signal the founding of the Paris Commune, one of the significant events of the 19th-century Europe. Socialists saw it as a vindication of their belief that only by resorting to force could workers hope to overthrow the rule of the bourgeoisie. Yet the truth, in retrospect, is more complex than legend and it must be conceded that national and sectional interests were involved in the tragedy. Paris had declared itself independent of France and had to be brought back into line before peace with Prussia was possible. The end of the Commune brought vengeance and bloodshed; 20,000 were killed and 50,000 arrested.

Figure 6. Karl Marx was the father of modern socialism. His political views are outlined in the Communist Manifesto, his views on political economy in Das Kapital (capital).

In the mid-19th century most people with any political awareness would almost certainly have described themselves as either "liberals" or "conservatives". The conservatives would have had little difficulty in explaining what they were and what they stood for, namely the established order. They were firmly against radical change and followed the line laid down by Edmund Burke (1729–1797) in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in 1790. This insisted that state and people alike were products of imperceptible, natural and organic growth and that artificial change based on general theories was self-defeating.

In the realm of practical politics, however, it was not quite so easy to preach and practice conservatism – particularly after the fall of the Austrian statesman Prince Metternich (1773–1859) in the revolution of 1848. Metternich refused to concede that any kind of change was permissible, if only as a tactical maneuver to prevent more radical developments, and was ultimately obliged to take refuge in England.

Metternich's downfall was one of the factors that encouraged the British prime minister, the astute Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881), to present the country with a Second Reform Bill. Meanwhile in Germany Prince Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) introduced universal suffrage and limited social welfare legislation. In France, Napoleon III (1808–1873) had embarked on similar action.

|

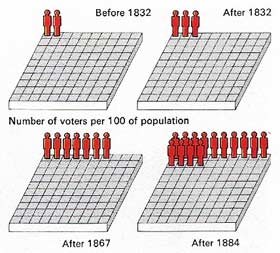

| A new British electoral system was created between 1832 and 1885, based on a series of Acts of Parliament. The result was that by 1886 two-thirds of the adult male population of England and Wales, and three-fifths in Scotland, had the right to cast their vote in secret. The measures that brought this about were three Representation of the People Acts, a Ballot Act and two Acts to redistribute the seats and prevent corruption. |

The decline of liberalism

Liberals were distinguished by the belief that progress could be achieved by means of "free institutions". In Britain and France this usually referred to a freely elected parliament, with ministries responsible to it, an independent judiciary, freedom of speech and religion, freedom from arbitrary arrest, and freedom to acquire and safeguard property.

In Russia a "liberal" might merely be someone who advocated a strong state council to advise the tsar. But even in France there were "liberals", including Francois Guizot (1787–1874), the statesman and historian, who believed that institutions were already as free as possible – a belief that made them seem highly conservative.

One of the most interesting themes of 19th-century European history is the decline of liberalism as a real political force. The main reason for the collapse was that, although the liberal ideal of making a framework of free institutions was born of the Enlightenment, once erected it became a bastion behind which the propertied classes defended their vested interests. The Continental turmoil of 1848 saw middle-class liberals deserting their ideals when faced with the prospect of sharing power with the lower-paid and less-educated sections of society.

|

| Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876), a Russian aristocrat, resigned his commission in the Imperial Guard to become Europe's leading anarchist. Not surprisingly his life was eventful: he was sentenced to death by the Austrians and the Prussians and was sent to Siberia by his own country, he escaped in 1861 and spent the rest of his life advancing anarchism in western Europe. Unlike the socialists, he believed that society could only be overthrown through individual revolt. |

The rise of socialism

The creed that began to appeal to many of those apparently abandoned by liberalism was socialism, and the greatest socialist thinker of the century was without doubt Karl Marx (1818–1883) (Figure 6). The young Marx of the first half of the century drew his ideas from a wide variety of sources but the foundation of his beliefs was the conviction, derived from the German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770–1831), that history was progressive, had objective meaning and would reveal this meaning through a series of revolutionary jumps.

The Communist Manifesto of 1848 reflected Marx's faith in the success of the European revolutions of that year, but with their ultimate failure he laid more stress on the deterministic aspects of his thought. He predicted that bourgeois society would col-lapse as a result of its own internal contradictions. Capital, he said, would become concentrated in fewer hands until the oppressed workers would be forced to revolt against their exploiters. A "dictatorship of the proletariat" would then emerge, paving the way for such social harmony that the state could wither away. The Paris Commune (Figure 5) revived his faith in revolutionary activity and in the 1870s he even toyed with the possibility of a peaceful overthrow of the social system through the ballot box with the aid of a fully enfranchised proletariat.

The development of nationalism

It was not the thoughts of Marx, however, that dominated the nineteenth century. By far the greatest force was nationalism, which conquered both the liberals and the socialists. In 1815 nationalism was still weak in Europe, but only 45 years later the philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was to write that it was "in general a necessary condition of free institutions that the boundaries of government should coincide in the main with those of nationalities".

Meanwhile nationalism had developed in many ways. The German philosopher Johann Herder (1744–1803) had insisted before the end of the eighteenth century that men's minds were conditioned by their cultural environment and, especially, by their language. Other thinkers took up this theme at the beginning of the new century and subsequently gave rise to many linguistic revivals. European scholars compiled dictionaries and grammars; folk-songs and folk poetry were collected; national histories were written. This, in turn, stimulated political demands and national wars radically redrew the map of Europe. The rest of the world did not escape: frustrated nationalism led to adventures overseas and the great wave of imperialism.