industrialization 1870 to 1914

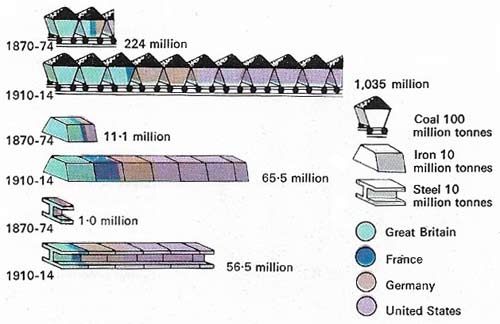

Figure 1. Industrial output rose rapidly in the latter half of the 19th century aided by advances in engineering and financial expertise. The 1878 Thomas-Gilchrist process to make steel from phosphoric iron ores enabled France and Germany to base industrial expansion on vast ore deposits. This diagram shows average yearly production between 1870–1874 and 1910–1914.

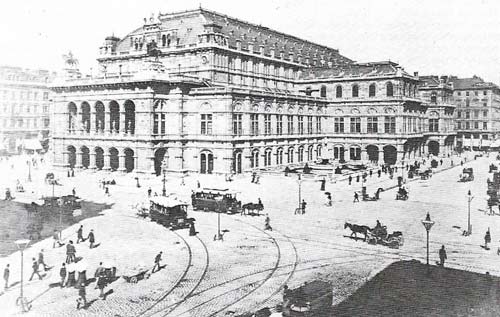

Figure 2. Opera houses such as that of Vienna were part of an impressive urban culture created by the growing wealth of many European cities, which built concert halls, art galleries and museums together with municipal buildings and better systems of sanitation, lighting and street paving. Improved housing for better-off workers and the middle classes led to the first suburbs and mass transport by tram and railway.

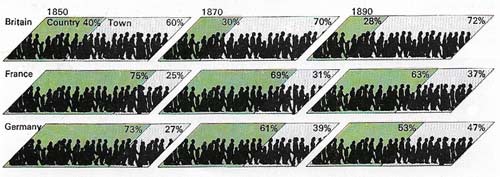

Figure 3. A population shift from the country to the cities proceeded rapidly as industrialization spread. In 1850, Britain apart, nearly three-quarters of Europe's people still lived on the land. But as Germany industrialized, its population ratio began to alter in the direction of Britain's - a trend followed by France towards the end of the century.

Figure 4. The bicycle was the first "luxury" consumer product to gain a mass market. Heavily promoted by colorful advertisements such as this from the Michelin Building, London. It was sold in such numbers that manufacturers realized a huge new market had been suddenly created. Other mass-produced goods developed through advances in engineering and metallurgy, including sewing machines, gramophones, typewriters, and motor cars.

Figure 5. Victorian families of all classes tended to be large because of a high birth-rate and declining mortality due to improved medical care, diet, and general living standards. Among poorer sections of the community infant deaths from infectious diseases continued to be high and there are usually more pregnancies than surviving children. But upper-class family life was based on large units with many servants as well as children. Two or three servants were a bare minimum for a solid middle-class family. In the aristocratic households of the great country estates it was not unusual to find over 100 servants, kitchen staff and gardeners. The rambling Victorian house was often a viable living unit only when it could be maintained by numerous staff.

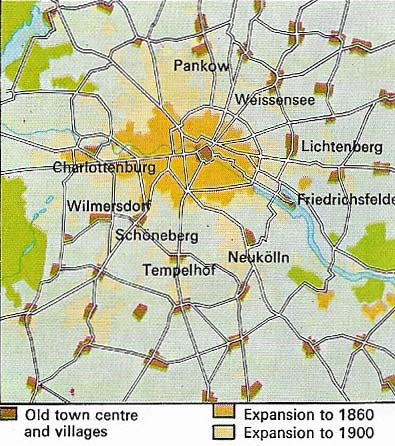

Figure 6. The growth of Berlin was typical of many 19th-century cities. Up to 1860 its expansion was mainly around the old city center, but with the growth of the German state, and the development of Berlin as a capital city and industrial centre, it grew into a major European metropolis. As with many other cities, Berlin's rising population spread out to create surrounding suburbs, incorporating villages that have once and separate.

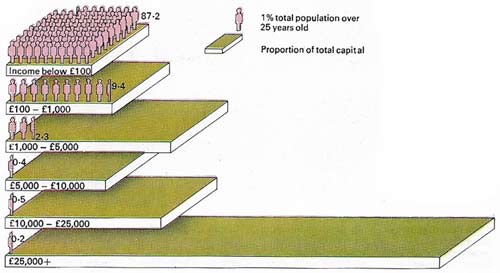

Figure 7. Much of the wealth created by the Industrial Revolution was concentrated in the hands of the upper classes. In Britain in 1911, as shown here, a tiny group of wealthy industrialist and aristocrats still disposed of a large share of the national income, although a growing proportion was held by the lesser industrialists and professional men.

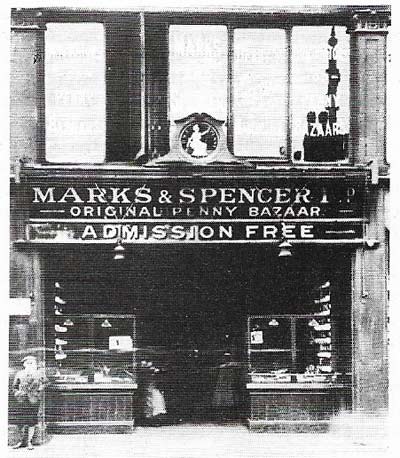

Figure 8. Growing wealth for all sections of society in the late 19th century led to the first mass consumer market with the development of advertizing and the growth of chain stores, among them Marks & Spencer, who opened a "penny bazaar" in Stretford Street, Manchester, in the 1890s.

The most striking feature of the latter half of the 19th century was the growth and spread of industrialization through Europe and into other parts of the world such as Japan and the United States. The rise of industrial economies in Western Europe had profound social and political consequences. With the rapid growth of cities and towns came the development of a more complex political society in which new groups of people – the middle and working classes in particular – began to group themselves and exert greater political influence than before.

Spread of industrialization

In 1850 the only country that could be described as having an industrial economy was Britain (Figure 3). But industrial development spread to Belgium, France and Germany by 1870, and in the last decades of the century was becoming established in countries such as Sweden and Russia.

Belgium industrialized rapidly and by 1870 had one of the leading economies in Europe. French commerce, iron production and textile output were flourishing by the latter part of the century and between 1870 and 1890 French technical innovation played an important part in the development of many engineering products.

By 1900 the most important industrial economy to emerge on the continent of Europe was that of Germany. Her unification by 1871 was accompanied by an accumulation of capital and development of the transport network. From 1850 to 1880 Germany increased coal production tenfold and, with the acquisition of the iron ore fields of Alsace-Lorraine from France in 1871, output of iron and steel rapidly expanded (Figure 1). Other countries, such as Sweden, Russia, Switzerland and Austria, began to share in these developments by 1900.

Technology and trade

European industrialization rested upon the application of a technology pioneered in Great Britain, but made use of more advanced techniques. The Bessemer process for making steel, invented in 1856, enabled the cheap production of a material that was stronger than iron. Steelmaking from the phosphoric ores common in Europe was made possible by the Thomas-Gilchrist process after 1878. Cheap steel could be used for machinery, shipbuilding and many other items of general use and provided the basis for the rapid expansion of engineering industries throughout Europe. By 1900, with scientific inquiry into chemical and electrical phenomena, other new industries appeared. The first electrical apparatus and industrial chemicals began to emerge, especially in Germany. Development of the internal combustion engine was well under way by the turn of the century and refinements in mechanical engineering provided the impetus for a flood of labor-saving products ranging from sewing-machines and vacuum cleaners to typewriters.

Trade expanded rapidly during the late nineteenth century, facilitated by the increasing use of iron and steel steamships. Imperialism stimulated the search for new markets and raw materials but the bulk of trade occurred between European and American markets. Cheap foodstuffs from North America after 1870 played an important part in reducing European food prices while at the same time depressing local agriculture in what was called the "Great Depression". Established industries, too, were exposed to fluctuations with the rise of competing industrial economies. To protect their newly established industries France and Germany imposed tariffs. A more complex economic structure emerged with large trusts and cartels grouping related industries into large combines; joint stock companies sup-planted many family firms and banking and investment institutions became more sophisticated. By 1914 London was the financial center of the world, with large stakes in shipping, insurance and investment.

Far-reaching social changes

Industrial development and the continued rise of Europe's population associated with European urbanization (Figure 6) brought fundamental social changes. There was a great increase in middle-class wealth, often derived from investment in stocks and shares. But even the poorest classes benefited from rising real wages. Living conditions in the growing towns and cities of Europe were often harsh and difficult, but were improving at record rates. Social welfare measures began to be adopted by some states, as in Bismarck's Germany, and philanthropy in countries such as Britain provided some relief for the most deprived. Emigration was widespread from the poorest countries, especially Ireland, Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most migrants went to North America, although some went to British colonies, in particular to Australia.

An advance in living standards by 1900 was reflected in the emergence of the first aspects of mass consumer society (Figure 8). The rise of cheap newspapers, widespread advertizing and selling of consumer goods such as bicycles (Figure 4), and the growth of mass entertainment in sport, music hall and holiday excursions, showed that the working classes were beginning to enjoy some of the fruits of industrialization. This was certainly the case with the large middle-class families (Figure 5) who gave the latter part of the nineteenth century a somewhat staid character that belied the changes at work in society.

|

| London celebrated the relief of Mafeking in 1900 during the Boar War with an outburst of national pride fuelled by widespread reporting of the war in the popular press. The rise of mass newspapers helped to create a powerful and excitable public opinion in the last decades of the century, when imperial adventures in colonial rivalry gave birth to "jingoism" expressed in bellicose literature, spirited demonstrations and songs. |