Nelson and Wellington

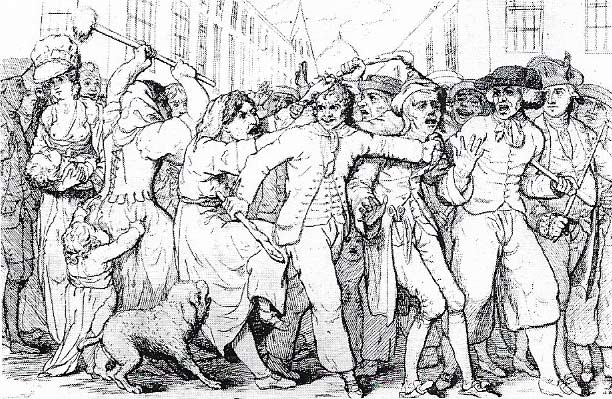

Figure 1. The hated press-gangs, armed with cudgels, terrorized towns as they went ashore and roamed the streets in search of able-bodied men for the navy. Victims were forcibly seized and dragged aboard for medical examination, volunteers were few, for life at sea meant separation from their wives and families for long periods, bad food, wretched conditions and brutal discipline; yet morale under Nelson was high.

Figure 2. Women were considered to be more a hindrance than a help in the army of Wellington's day, as implied in this drawing by Thomas Rowlandson. Some wives, but not many, were allowed to accompany their husbands on a campaign: the number we limited to between 2 and 6 per company of 100. Those women who did go received half-rations free. Some even took children as well. The women cooked meals, did soldiers' washing and acted as nurses. They had an eye for booty, too. Wellington once observed that "The women are at least as bad, if not worse, than the men as plunderers".

Figure 3. The French took Spain swiftly and compelled the British to leave. After Oporto fell (1807) Portugal appealed to Britain for aid and Wellington sailed with a force of 17,000. Napoleon ordered his commanders to drive the British into the sea, but the French themselves were expelled from the Peninsula and sent scurrying across their own border, with Wellington in pursuit. Napoleon later said that the "Spanish ulcer", with constant guerrilla activity and rioting, undermined his empire.

Figure 4. HMS Victory, Nelson's flagship at Trafalgar, was typical of the ships-of-the-line that formed the main battle fleet. Floating batteries with 60 to 120 guns firing in broadsides and a complement of 700, these slow, unwieldy vessels could remain at sea for years on end. Built at Chatham, and launched in 1765, Victory was 69.5 meters (227 feet) long with a beam of 15.5 meters (52 feet). She had more than 100 guns, the largest of which were two 68-pounders, 30 32-pounders and 28 24-pounders.

Figure 5. At Trafalgar the British fleet went into action in tow columns. Realizing that he was outnumbered 27 to 33, Nelson eschewed traditional tactics of the single line of battle, and succeeded brilliantly, capturing 19 enemy vessels.

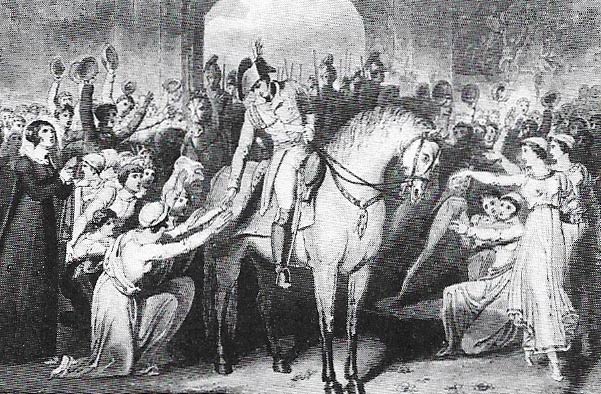

Figure 6. Wellington had a great welcome when he rode into Toulouse on 12 April 1814. The battle, he said, had been "very severe": combined deaths were 7,700. Victory, however, seemed complete when he learnt later that day that Napoleon had abdicated.

Figure 7. The Battle of Waterloo (1815) made Wellington a national hero. Napoleon had crossed into Belgium on June 15 and thrust back the Prussian army at Ligny but failed to rout them. Then on the morning of Sunday, 18 June, he attacked Wellington at Waterloo, Wellington had 67,000 men with 150 guns, Napoleon had 72,000 with 250 guns. The battle soon became a pounding match with few maneuvers, but the arrival of the Prussians in the early evening brought swift and total victory.

For many centuries, Britain opposed any European power that threatened to dominate Continental Europe. From 1793 to 1814, with a short break in 1801–1802, it fought to defeat the spreading power of revolutionary France. Lacking a large army, Britain had to rely on the traditional strategy of organizing alliances of other continental powers while using its naval supremacy to weaken France by blockade. Whenever possible, troops were sent to help anti-French forces, but Britain's major contribution to the ultimate defeat of France were a willingness to continue fighting, alone if necessary, until new allies were found, and the use of a long-established prowess at sea.

Britain's weapons

The Royal Navy had long been recognized as the bulwark of British security but conditions of service were grim. The numbers of recruits needed to man the wartime fleet could only be maintained by forcible impressment (Figure 1) and the recruitment of convicts. Once enlisted, men were rarely allowed to leave.

In contrast to the conscript armies of Europe, the British army at that time was a small volunteer force numbered in tens, rather than hundreds, of thousands. Officers were able to buy their commissions, received no professional training and usually paid scant attention to the welfare of their men. By the end of the 18th century, however, efforts were being made to organise supply and medical services (Figure 2).

Nelson's great triumphs

Throughout the Napoleonic Wars, Britain was fortunate to be served by a number of exceptional naval officers who proved to be both fine seamen and outstanding leaders. The greatest of these was Horatio Nelson (1758–1805).

At the outbreak of war, Nelson commanded a ship-of-the-line in the Mediterranean and acquired a reputation as an active, able officer. During the Battle of St Vincent on 14 February 1797 his initiative in breaking the line of battle led to the capture of four enemy ships. For his part in the victory, Nelson was knighted and promoted to rear-admiral. Wounded in several engagements, he lost an eye and an arm but his mental powers remained undiminished. In 1798, when Napoleon attempted to cut Britain off from India and its other eastern possessions by invading Egypt, Nelson annihilated the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile, fought in Aboukir Bay. Of the 17 French ships, 13 were captured or destroyed.

The victor of the Nile, now created Baron Nelson of the Nile, took command of the Mediterranean fleet in 1803. For the next two years, in a remarkable display of seamanship, Nelson off Toulon and Admiral William Cornwallis (1744–1819) off Brest kept the French fleet immobile. In 1805, the Toulon force managed to slip out and head for the West Indies meaning to return, link up with other forces and establish temporary command of the Channel so that Napoleon could invade Britain. But the French were forced into Cadiz while the British gathered outside under Nelson's command off the Cape of Trafalgar. When the combined French and Spanish fleet emerged it was utterly destroyed in battle on 21 October 1805. Although Nelson was killed on the quarterdeck of HMS Victory (Figure 4) at the height of the engagement (Figure 5), he died knowing he had won a decisive victory.

|

| Nelson's death overshadowed the triumph of Trafalgar. Hit on the shoulder by a musket-ball from a sniper, he was taken below decks where he died four hours later. A stern disciplinarian and a born teacher, he displayed in battle great bravery and daring, tactical genius and shrewd judgement. His devotion to duty was absolute and the men he led revered him. |

The road to Waterloo

Nelson's success ended any hopes Napoleon had of invading Britain. The French emperor was therefore forced to try to destroy Britain by closing Europe to British trade. When Portugal and Spain refused to join the blockade, the French invaded. Britain was thus given the opportunity to intervene militarily. An expedition to Spain under John Moore (1761–1809) was compelled to retire but in August 1808 a second force under Sir Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852)), later Duke of Wellington, landed in Portugal.

An Anglo-Irish aristocrat, Wellington learnt his soldiering skills in India from 1796 to 1805. After taking part in unsuccessful expeditions in north-western Europe in 1806 and 1807 he was given command in the Peninsula. There for the next three years he showed great skill in tying down vastly superior French forces (Figure 3). He was always prepared to withdraw behind defences when necessary, but emerged to inflict a succession of defeats on the French. Finally in 1811 he launched a major offensive that cleared the Peninsula, winning major victories at Salamanca and Vitoria before invading south-west France in 1814 (Figure 6).

|

| "A Wellington Boot, or the Head of the Army": this 1827 cartoon shows the Iron Duke's distinctive profile and characteristic footwear. Taciturn and aloof, he affected to despise the troops he commanded as the "scum of the earth" but he based his tactics on their steadiness under fire. He chose defensive positions and relied on the discipline of his men to break the massive infantry and cavalry assaults of the French which had shattered most other adversaries. He hid an emotional nature under an Icy manner and he cared for the welfare of his men. They repaid him with their respect and by beating the finest troops of Napoleon's Grande Armee. |

Napoleon abdicated and left for exile in Elba, but almost a year later he returned to France in an attempt to regain the throne. To meet this renewed threat, Britain and the allies – Austria, Prussia and Russia – appointed Wellington to command a combined army gathered in Belgium. Despite being surprised by the speed of Napoleon's opening maneuvers, Wellington held his ground against superior forces near the village of Waterloo (Figure 7) until the arrival of a Prussian army under Marshal Gebhard von Blucher completed a crushing victory. For the second time, Napoleon abdicated and went into exile – this time to St Helena, until his death in 1821. The victories of Nelson and Wellington, coupled with the nation's industrial and commercial supremacy, now made Britain the most powerful nation in the world.