the Reformation

Figure 1. The sale of indulgences was to raise money for the rebuilding of St Peter's in Rome. An indulgence was originally a remission from punishment for a sin and was conditional on the sinner's sincere repentance. But in the Middle Ages, indulgences came to be granted to sinners who did good works, such as going on crusades or contributing money to the building of a church. This led to the idea that forgiveness could be purchased as a commodity.

Figure 2. Encouraged by Luther's success and sharing some of his ideals, the peasants of the southwest and central German states rose against their rulers in 1524. But Luther denounced their complaints – mainly political social and economic – and in the face of stern repression the revolts collapsed.

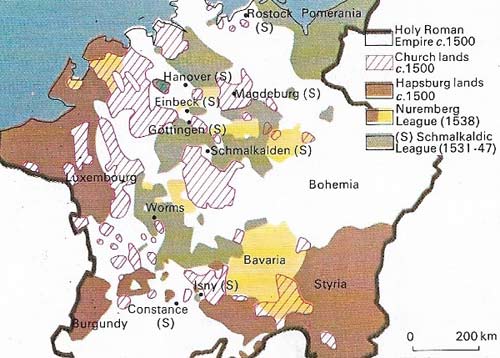

Figure 3. The Holy Roman Empire, in theory the political expression of the Catholic Church, was in practice a grouping of rival German states. The Reformation provided the chance many of them had been waiting for to defy the power of the emperor. The Protestant rulers formed themselves into the Schmalkaldic League in 1531 and the emperor replied with the Nuremberg League in 1538. War seemed imminent but a compromise was reached in 1539.

Figure 4. The Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) inherited the lands belonging to the Austrian and Burgundian Hapsburgs and also the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile. This provoked the fear of France, which fought throughout his rule to prevent encirclement, and encouraged German Protestant princes to defy his authority. Defeated in his ambition to reunite Christendom, he gave his possessions to his brother and son.

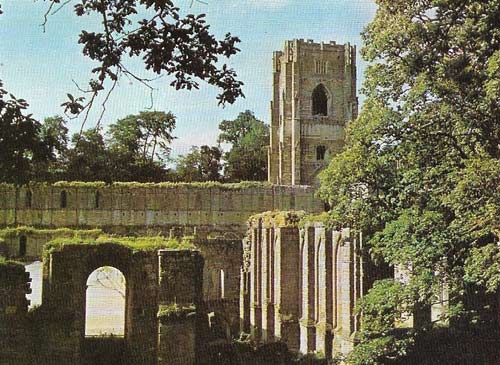

Figure 5. Fountains Abbey was among the finest religious houses destroyed during the dissolution of the monasteries in England (1536–1540). The first act (1536) based dissolution on whether a monastery enjoyed an annual income of less than £200. The Act for the Dissolution Monasteries (1539) completed the process. Pensions were paid to monks refusing to join the secular clergy and the Crown took the rest. A few lands were kept by the Crown, a few given away, but most were sold to gentleman farmers, thus creating a new class of landowners with the strongest reasons for staying loyal to the new order.

Figure 6. Under John Calvin the Swiss city state of Geneva became the most influential single center of the Reformation. Its citizens lived under the strict moral rule of the Calvinist Church, which readily burned opponents such as the anti-Trinitarian "heretic" Michael Serventus in 1553.

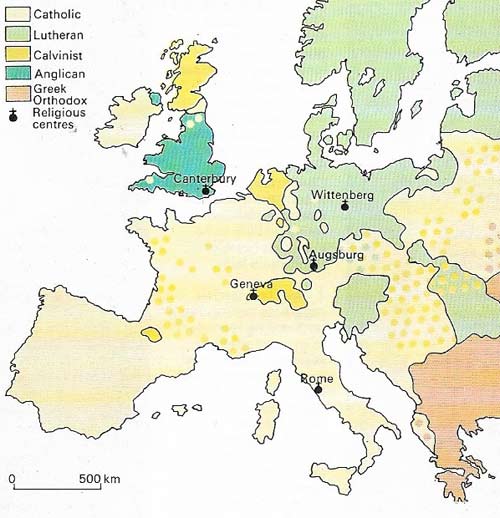

Figure 7. By 1560 Lutheranism had spread from north Germany to Scandinavia, Poland and Hungary along German trade routes and among the scattered communities in the trading cities. After 25 years of religious wars the Peace of Augsburg (1555) had given the Lutheran princes and cities the right to freedom of worship, in effect strengthening the hands of both Catholic and Protestant rulers within their own territories. But it gave no privileges to the followers of Zwingli and Calvin, who were the dominant religious groups in The Netherlands, Scotland and most Swiss cantons, and who formed a substantial Swiss minority in France, Hungary and southern Germany.

Figure 7. Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk, was the first great inspirer of the Reformation. On a visit to Rome in 1511 he was appalled by the wealth and spiritual emptiness of the Catholic Church so different from the ideals of primitive Christianity. These ideals became his watchword as he argued against the Church's corruption in his Ninety-Five Theses (1517). Luther was not a revolutionary, for he retained vestments and certain Catholic ceremonies, but in his reformed Church the communion cup was given to the congregation, saints were no longer objects of special prayers and Church wealth went to pastoral and educational activities.

When Martin Luther (1483–1546) posted his Ninety-Five Theses on the door of the Castle Church, Wittenberg, Saxony, on 31 October 1517, he was initiating a religious debate in the traditional fashion. But the consequences of his protest were revolutionary and heralded a new historical era: the end of the dominance of a single European Catholic Church in the Middle Ages; the creation of "reformed" or Protestant Churches; a century and a half of "religious" wars that convulsed the emerging nation states of Europe; and a new understanding of the Christian faith that has personally affected millions of men and women throughout the world. All these developments are historically part of "the Reformation".

The original intention

The term Reformation precisely describes Luther's original intentions. His Ninety-Five Theses (Figure 7) were an attack on abuses inside the Roman Catholic Church. He denounced the frivolous uses to which the pope put his vast wealth and in particular the way in which he was raising money by the sale of "indulgences" (Figure 1), documents that the pardoner Tetzel claimed gave any purchaser automatic remission of his sins.

|

| The religious orders of monks, nuns, and friars provoked hostility. To ordinary people and reformers they seemed idle and excessively wealthy, spending their money on their own enjoyment – not in the service of God. They were envied but rulers for the valuable town properties and country estates. |

The history of the Catholic Church had for centuries, however, been a sequence of "re-formations", and for more than a decade before 1517 John Colet (c. 1467–1519), Erasmus, and Thomas More (c. 1478–1535) had been working to cleanse the Church of its follies. What made Luther more than merely a traditional reformer was his deliberate personal conviction coupled with the accidental political situation at that moment in Europe's development.

Luther's complaint against indulgences went beyond distaste of the money involved to a rejection of the whole concept of spiritual book-keeping with God. Luther felt a sense of infinite personal unworthiness that no amount of good works could ever overcome. As an Augustinian monk, a doctor of theology and then professor at the University of Wittenberg he had mortified himself mercilessly but still felt impure, repulsive, sinful – unworthy even to approach God's presence. Only blind faith could save him. From this conviction was born the doctrine of "justification by faith", which was to inspire the spiritual side of the Reformation. It involved great emphasis on the single gesture of faith – "conversion" – and rejected reliance on the priest as a middleman be-tween the believer and God.

|

| The translation of the New Testament by Erasmus (1466–1536) was an example of Catholic efforts to reform the Church from within. Erasmus satirised the follies and superstitions of the Church, articulating the dissatisfaction that many felt without wishing to divide Christendom against itself. At works such as In Praise of Folly (1509) even the pope felt safe to laugh. But Erasmus's intention was more to goad than to reform and he had little hesitation in denouncing the schism the Luther created. |

The effect on Germany

Luther's ideas, broadcast by the medium of the printing press, had a dynamic impact throughout Germany and were given immeasurable help in taking root by a fatal four-year delay on the part of the Catholic authorities. Pope Leo X (1475–1521), who hoped to strengthen his personal power by manipulating the imminent election of a new Holy Roman Emperor, adopted the traditional papal tactic of supporting a weak candidate for this position that carried so much influence in Germany. He had already selected as his protégé Frederick the Wise of Saxony (1463–1525), Luther's own ruler and protector. Thus Luther's teachings were not officially condemned until 1521 at the Diet (congress) of Worms.

Frederick the Wise then sent Luther into hiding for a year and the new emperor, Charles V (Figure 4), had neither the time nor the power to control this defiance to his authority. In 1520 Luther had urged princes to throw off the unbiblical authority Rome claimed over the Church in their states and rulers were not slow to profit from this invitation. In 1529 all the Lutheran states and towns in Germany put their names to a "Protestation" against the emperor – the origin of the term Protestant – and after more than 25 years of conflict the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 recognized the right of a ruler to determine his country's religion.

England and Switzerland

The principle of the rights of a ruler had been exercised by Henry VIII (1491–1547) in his Reformation in England, which was confirmed by the Act of Supremacy of 1534. It was essentially a forcible transfer of the supreme power over the Church from the pope in Rome to the English sovereign. As in Sweden in 1527 and Denmark and Norway in 1536–1539, there was little pretence that Thomas Cromwell's dissolution of the monasteries (1536–1540) was any more than a confiscation of the Church's wealth.

|

| The Bible replaced the priest as the ordinary man's spiritual authority, the scriptures were translated from the Latin and Greek and offered to the people in their own languages – notably German in a translation by Luther, and English in the King James Version of 1611. |

Only in Switzerland was the "purification" of the old Church's images and decorations a matter of genuine Christian austerity. In Zurich in the 1520s Huldreich Zwingli (1484–1531) had the church organs destroyed because their sound was profane while the citizens as a whole were banded into a new democracy of the faithful.

In Geneva (Figure 6) after 1541 Jean Calvin (1509–1564) created a holy city that gave shelter to more than 6,000 refugees fleeing from persecution in France, Italy, Spain and, during Mary's reign, from England as well. Calvin's book Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) enshrined the other great Reformation theme of "predestination" – that God chooses His own elect. It was the buoyancy of those who felt the assurance of their own election that inspired the Calvinists in the Netherlands as well as the Huguenots in France, the Presbyterians in Scotland and the Puritans in England and later in the New World.