Roman Republic: laws

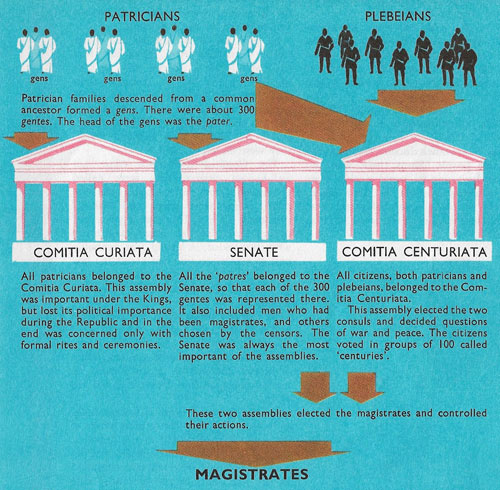

The government of Rome. In addition to the groups and offices shown, there was also the following:

DICTATOR: He was elected only in emergencies, and held office for no more than six months. During that time the powers of all other magistrates were suspended.

TRIBUNES OF THE PLEBIANS: The duty of the Tribunes was to defend the interests of the common people (the Plebs) and they were elected by them. They could veto any order of any other magistrates, which means they could stop the order from becoming law, if it would harm the Plebeians.

PRAETORS: They were concerned with law-suits.

CENSORS: The Censors were in charge of making people behave properly. They could prevent anyone who behaved badly from holding office.

AEDILES: The Aediles looked after the supplies of the City, the markets, and public entertainments.

QUAESTORS: The Quaestors looked after the State's money, collected the taxes, and paid the army and the civil service.

PONTIFFS: The Pontiffs looked after the worship of the gods.

CONSULS:

They were the most powerful men in the Republic. There were two and they had equal powers; each could veto the decisions of the other. They called the Senate together, and presided over it, they saw that the laws were carried out and they commanded the army.

In 509 BC when the Romans banished their last King and decided to set up a Republic, they found that they had to reorganize the life of their State on completely new lines.

Government under the Kings had been very simple. The King had full authority over everyone: he was the most important of priests, the head of the army, the highest judge, and he had full control over all state property. He held office for life. After the revolution, in order to prevent power remaining in the hands of one man, the Romans had to set up institutions for governing and appointed officials called magistrates who could prevent each other from becoming too powerful. They also made a set of rules which governed all the working of the Roman State.

These rules were not written down, or at any rate were not collected together, but they formed a real 'Constitution' of the State. A constitution is the most important law of any State for it lays down the powers of the State. A constitution may be written or unwritten, but its rules and principles and the institutions which it sets up provide a framework within which the State is allowed to govern. It is the supreme legal authority in the land.

|

| Roman senator.

|

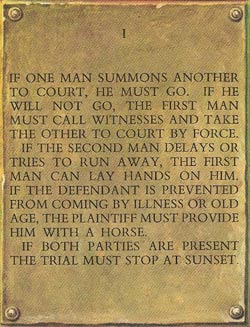

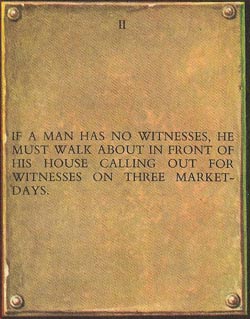

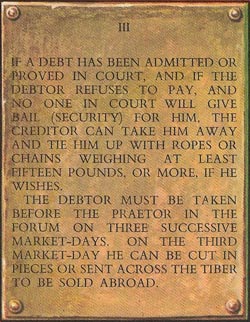

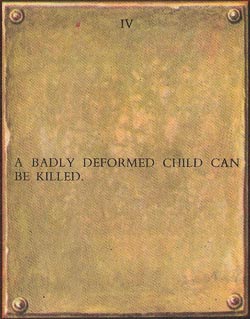

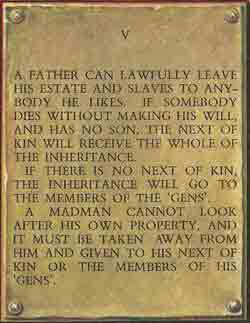

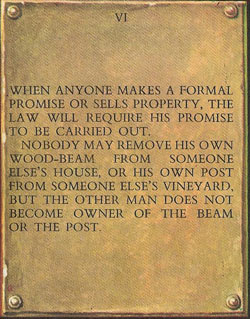

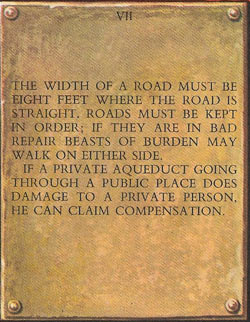

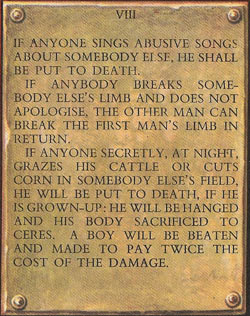

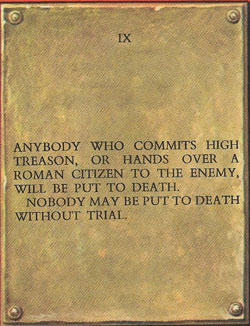

The XII Tables

In this article we discuss the first attempt of the Romans to codify their law. Certain customary (unwritten) laws were engraved on 12 bronze tablets which became known to history as the Twelve Tables. Every Roman schoolboy learned them by heart.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Code

The Code is a set of rules saying how citizens should behave towards each other and to the State, and what should be done to those who break the rules. One of the most important principles of all civilised countries is that the law is the same for everyone. In some countries this rule is often written on the walls of law courts, to remind judges that it is to be obeyed.

In Rome, at the beginning of the Republic, there was no code and the law was not the same for everyone. This caused much discontent among the common people. Since there were no written laws, judges could decide cases and condemn people as they liked. Citizens were not equal before the law, which was more severe on some than on others.

Those who suffered most from this state of affairs were the Plebeians. They had no education and no knowledge of the law; they were sometimes cheated and deceived by the Patricians.

In 462 BC a tribune of the Plebs called Terentilius Arsa demanded that there should be a written code of laws to be obeyed by all citizens, both Patricians and Plebeians. For ten whole years the Senate, who were all Patricians, opposed this demand, but at last, in 451, under the threat of a popular revolt, they were forced to yield.

The Comitia Centuriata chose ten well-known citizens who were called Decemviri (from decem – ten, and vir – man). They were given the task of preparing a code. This took a year, and during that time all other magistrates were suspended. A group was probably sent to Greece to find out about the law there and to study the code which the great Greek statesman Solon had given to Athens.

By the end of the year, the Decemviri had completed their work; the laws were submitted for the approval of the people, and were then engraved on ten tables of bronze and put up in the Forum, or market-place, so that everyone could see them.

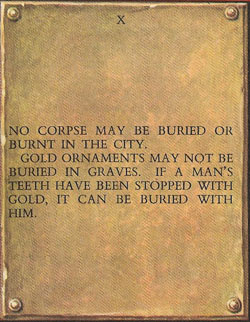

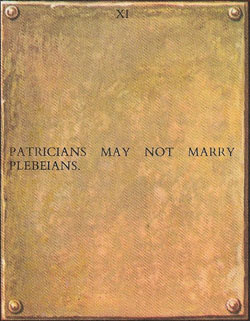

In the following year a second body of Decemviri prepared two more tables of laws, which were added to the first ten, making up a code of twelve tables. But the second Decemviri were not as fair-minded as the first, and in the eleventh table they introduced an unjust law forbidding marriage between Patricians and Plebeians. This law was repealed a few years later.

History tells that the bronze tablets on which the laws were engraved were lost when Rome was sacked by the Gauls in 386 BC. Later their text was reconstructed from memory; and generations and generations of Roman schoolboys learned it by heart. Only a few fragments exist today. These fragments are precious because of the importance of the Twelve Tables in the history of Rome and the human race. The code of the Twelve Tables was the first written text of the great body of Roman Law: and this law was the greatest contribution of the Romans to the civilization of the world.