Roman fleet

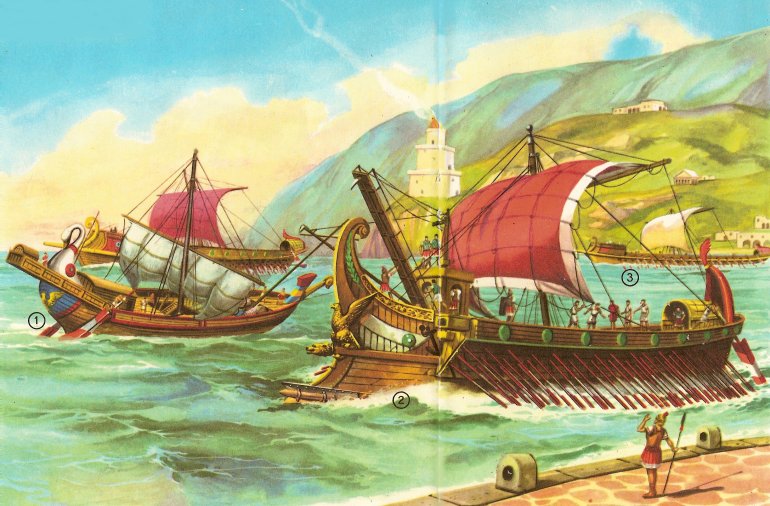

Roman ships maneuvering out of port: (1) a merchant ship, (2) a trireme, (3) a liburna.

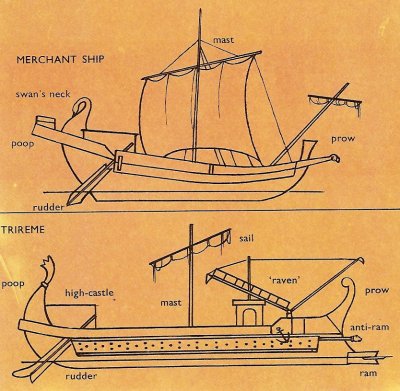

Roman merchant ship and trireme.

The position of rowers in a trireme.

In the year 264 BC, the Romans succeeded in conquering the whole of Italy. Up to that time they had only fought by land, since none of the people with whom they had had to battle was a naval power. But in that year the Romans saw that they would have to fight a people who had a very powerful fleet of warships – the Carthaginians (see Carthage). The Romans knew very well that unless they could fight them at sea they would never subdue the Carthaginians. So the Roman senate took a historic decision – that Rome should have a great navy. In a few months' time Rome had a fleet, and in 260 BC she was able to meet the Carthaginian ships in a battle off the islands of Lipari.

1. The merchant ship (navis onerarius)

Even before they built their navy the Romans had a good number of merchant ships. They were sailing ships and had no rowers. This was because they needed the greatest possible amount of space for their cargo. They were broad-beamed and had a large square sail, made of linen, papyrus, or byssus. This last was a very fine and valuable textile material, usually made of flax. The sail was usually white. The hull of these ships was made of pine or fir wood. The keel was constructed with great care, since it had to be solid and watertight. On the outside it was lined with tarred wool, and over that was put lead sheeting. With this protection, the water could not penetrate into the hold and the merchandise was kept safe and dry. On the stern was a kind of figure-head, shaped like a swan's neck.

With these ships the Romans developed their trade, especially in the ports of the Tyrrhenian Sea, to the west of the Italian mainland. They transported oil, wine, fruit, grain, and cattle. When the Romans began to fight at sea, the merchant ships served to carry foodstuffs, troops, horses, and war-machines such as catapults and rams.

2. The three-banked galley (trireme)

This was the type of warship used most by the Romans. It was from 100 to 120 feet long and about 18 feet in beam – about the size of a river pleasure steamer today. It had a mast which supported a large rectangular sail. Embroidered on this in gold were the name of the ship and the insignia of her commander.

The soldiers were stationed in a superstructure at the forward end, which we would call the forecastle. In the ship's waist were the mariners and rowers. In the stern, in the so-called high castle, were the captain, officers, and steersmen. The ship was steered by two very long oars.

The complete crew of the trireme was 250 men, divided into rowers, sailors, and soldiers. It was the soldiers who did the fighting, which consisted mostly of boarding enemy vessels. The trireme's weight was nearly 50 tons when loaded, and it was capable of a speed of 5 knots. There were also ships with five banks of oars, called quinqueremes, but the Romans seldom used them. They were too difficult to maneuver and too slow.

3. The liburna or liburnica

After their defeat of the Carthaginians, the Romans built much lighter and faster ships. The best of these ships was the liburna, so called because in it the Romans copied the pirates of Liburnia. It had only two rows of oars, and the Romans came to prefer it because of its great speed and maneuverability.

Armament

In the days before the invention of firearms the chief method a warship could use to attack an enemy vessel was to ram it. All warships had at their bows a ram or "beak". It was made of iron or bronze and it was used to smash the hull of the enemy during battle. The defense against the ram was the "anti-ram" – a kind of projection (which can be seen in the illustration) which limited the penetration of the enemy's ram. In the year 260 BC, the Roman consul, Caius Diulius, introduced an ingenious addition to a ship's armament, the "raven" – a kind of drawbridge ending in a hook like a raven's beak. When a Roman ship came alongside an enemy, it dropped the bridge in such a way that it fixed on to the deck of the enemy and prevented it from withdrawing. The soldiers then crossed the bridge on to the enemy deck, thus turning the naval battle into a sort of land battle. After the discovery of the raven the Romans won many victories.