the Stuarts and Parliament 1600 to 1642

Figure 1. James I told Parliament in 1610 "The state of the monarchy is the supremest thing on earth". On several occasions James, a genuine scholar, spelled out the implications of the theory of the divine right of kings. Both he and his audience took it for granted that the monarch, as the earthly representative of God, was the basis of all political authority. But as the Stuarts persisted in policies that seemed evidently wrong, the assumption eventually came into question. In its stead, Parliament began to assert the traditional authority of the Common Law, which was propounded in an extreme form by Edward Coke (1552–1634), who helped to draft the Petition of Right (1628).

Figure 2. The Gunpowder Plot (1605), was an attempt on the king's life by a few religious fanatics desperate at their failure to secure a relaxation of the laws against Catholicism on James's succession. Its discovery raised fear of Catholicism to fever pitch, and this hysteria was repeated during the crisis of 1640–1641).

Figure 3. Charles and Buckingham went to Madrid in 1623, hoping to secure Charles's marriage to a Spanish princess. The plan was the culmination of James's policy of peace with Spain. But the policy was unpopular at home; Charles's return unmarried (shown here) was greeted with great celebrations. He and Buckingham then allied with the critics of James's foreign policy and helped first to bring down Lionel Cranfield, the Lord treasurer, and his regime of strict economy, and then forced James into a war with Spain that he could not afford. Enthusiasm for the war soon declined.

Figure 4. Henrietta Maria (1609–1669), a French princess, married Charles in 1625. The match was unpopular, especially because he tolerated he Catholicism. She led a court faction against Laud and Wentworth.

Figure 5. This religious cartoon sets the orthodox Anglican cleric holding the humanly inspired Book of Common Prayer alongside the papist priest with his Devil-inspired superstitions and against the Puritan minister with the divinely inspired Bible. Thanks to Charles's intransigent support for Arminianism, the minority opinion that "root and branch" reform of the Church was necessary grew in strength in the 1630s. So, as well as questioning the king's right in law to command an army for Ireland and Long Parliament also challenged the validity of episcopal authority in general.

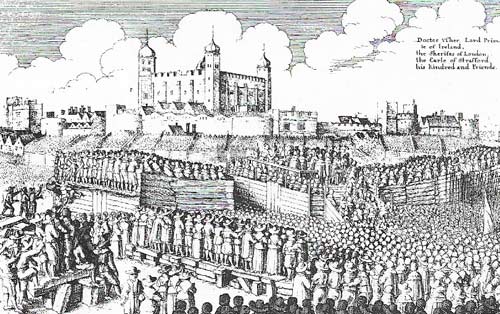

Figure 6. Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford (1593–1641), was a critic of Buckingham in the 1620's but entered Charles's service in 1628 fearing that the Commons might undermine royal authority. He was made the scapegoat for the "11 Years Tyranny". He was attainted by Act of Parliament (1641) and Charles could not protect him, under pressure from the London mob, which, as an organized pressure group increasingly threatened the king. Wentworth's execution, shown here, was a vital victory over Charles.

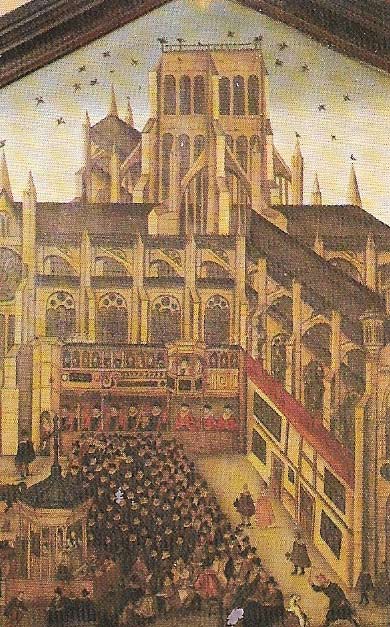

Figure 7. Preaching was the principal means of influencing public opinion or spreading information in the 17th century. Charles I said "People are governed by the pulpit more than the sword in times of peace". The regulation of sermons and religious lectures was an area of dispute between the Puritans and the Church authorities, especially the Arminians. St Paul's Cross, seen here, was the main preaching place in London and was carefully controlled by the government. Social and political implications, as much as theological ones, made religion a sensitive issue. James was reluctant to impose any aggressive religious policies, and often engaged in theological disputes.

In 1603 the peaceful transfer of the English crown to James VI of Scotland (1566–1625), who thereby became James I of England (Figure 1), was greeted with joy and relief. The collapse of the new Stuart dynasty was not inevitable. There were, however, severe stresses in seventeenth-century England.

Deep-rooted problems

Royal service and its ensuing favors were important to the landed classes and they formed a staple issue in politics. Elizabeth I had played off the resulting factions against one another to preserve her freedom of action. The rebellion (1601) of the Earl of Essex (1566–1601) destroyed this system and left Robert Cecil (1563–1612), Burghley's son, as the Crown's dominant adviser. James's predilection for favorites eventually brought this monopoly to the Duke of Buckingham. This monopoly encouraged corruption in the search for and exploitation of patronage and office.

|

George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham (1592–1628), was a younger son of a minor Leicestershire squire. In 1615 he captivated James by his physical charm and athletic prowess and he “jumped higher than ever Englishman did on so short a time, from private gentleman to a dukedom”. The interest of Villiers and his family in corruption prevented any possibility of reform, and his moderate abilities did not justify the military and diplomatic authority he was given. He gave James and Charles uniformly bad advice and encouraged them on short-term decisions that always led to honor and profit for Buckingham. He was assassinated in 1628 after he had involved England in war with France as well as Spain, and inspired disastrous and much criticized expeditions against Cadiz (1625) and to La Rochelle three years later. |

The amount of administration required of government in defense and foreign policy and in management of the economy, social problems, and reform in the Church had been steadily growing during the Tudor period. By 1600 the available machinery and money were inadequate. Central government was wasteful, and in the country the Crown depended on voluntary work by the gentry, who were deeply suspicious of central authority, hard to discipline and capable of wilful inertia. In Parliament the representatives of that same gentry were unwilling to vote the Crown an adequate share in the increasing national wealth. In 1610 an attempt at basic reform of royal finances (the Great Contract) proposed to exchange the Crown's profit from the wardship of minors and other feudal impositions for a regular peacetime tax. Its failure led the king to exploit for cash his rights of monopolies, customs, wardships and grants of honor.

Parliament's unwillingness to pay for what was needed meant that it had no effective control over the actions of the government. The king could defeat attempts to put pressure on him by dissolving Parliament. and there were real fears about its permanent survival. Before the 1640s it had little thought of any constitutional limitation of the king's power; agitation about parliamentary privileges arose directly from concern about the king's policies. To have any influence, Lords and Commons had to work together, and in the 1620s much parliamentary protest was engineered by nobles who wished to oust Buckingham.

|

| John Eliot (1592–1632), once a protégé of Buckingham, led the outspoken opposition to Charles's policies on the Commons in 1629. He criticized government negatively and believed in the divine right of kings. |

James's revenue and foreign policy

James I was not the man to make the necessary major reforms and in two areas he made matters worse. First, the royal finances had been affected by inflation, and Elizabeth left a debt of £100,000 net, 30 percent of her annual peacetime revenue. By 1608, however, James's wanton extravagance had increased the royal debt to some £500,000. Second, in the field of foreign and religious policy, James ended Elizabeth's Spanish War in 1604 in favor of a sensible policy of avoiding European conflicts. As pressure grew against Protestants in Europe with the start of the Thirty Years War in 1618, the king's determined policy of peace and his attempts to negotiate with Madrid looked like appeasement of Catholicism (Figure 4). Although James was personally a convinced Calvinist, he flirted with the growing High-Church or Arminian faction in the Church, which stressed ceremony, tradition and episcopal authority. To most Englishmen, Arminians seemed little better than Catholics, and the king's toleration of them looked extremely dangerous (Figures 5 and 7).

Charles and the rise of opposition

Charles I (reigned 1625–1649), unlike his father, asserted his authority without regard for his dependence upon the cooperation of its subjects. In the Book of Orders, 1631, he attacked the local autonomy of the JPs, insisting on a uniform performance of their duties. Autocratic rule by the Earl of Strafford( Figure 6) in Yorkshire and Ireland seemed ominous for the country at large. Charles's archbishop, William Laud (1573–1645), imposed Arminianism on the Church in many areas, including Scotland in 1637. Immoderate opposition in the House of Commons in 1629 impelled Charles to rule without Parliament. Ship Money, an occasional local rate, became a nationwide annual tax in the 1630s, extending taxation to yeomen and freeholders, hitherto largely exempt.

|

Charles wore this elaborate costume in January 1640 in the masque Salmacida Spolia at a time when Scotland was in rebellion. It was light blue cloth embroidered with silver, white stockings, a silver cap and white feathers. The isolated culture of the court, symbolized by these Inigo Jones masques and Charles’s patronage of such artists as Rubén’s and Van Dyck, presented the image of Charles, the embodiment of virtue, ruling an idyllic, contented and peaceful nation. But in this, his last masque performance, he played the Platonic king responding to adverse times with endurance and patience, a new image of himself that he retained until his death in 1649. |

Although Charles increased his income to a million pounds a year, this was insufficient to oppose a rebellion against Laud in Scotland in 1639. Appeals for money were turned down, JPs refused to act, and the forces raised by Charles mutinied. The Scots occupied northern England, and to pay their wages off Charles was forced to call Parliament for the first time in 11 years.

The Long Parliament (1640–1660), called after the Short Parliament (1640) failed to support Charles, was at first overwhelmingly traditionalist and quickly destroyed the alleged novelties of Charles I's "personal rule". A rebellion in Ulster in October 1641 forced Parliament to choose between trusting Charles with an army or insisting on revolutionary constitutional limitations before finding the money to quell the revolt. Polarization on the need for guarantees or the dangers of constitutional change, which would imply social change, split the political nation and led to the outbreak of war.