English Revolution

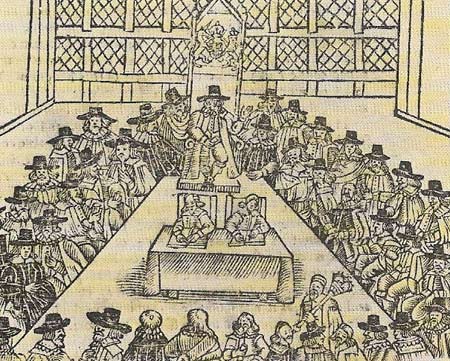

Figure 1. Parliament was a well-established institution before 1640 with its own traditions, procedures, and privileges. In the House of Common’s chamber there were a Speaker (center), two committee clerks, the sergeant-at-arms (carrying the mace) and MPs.

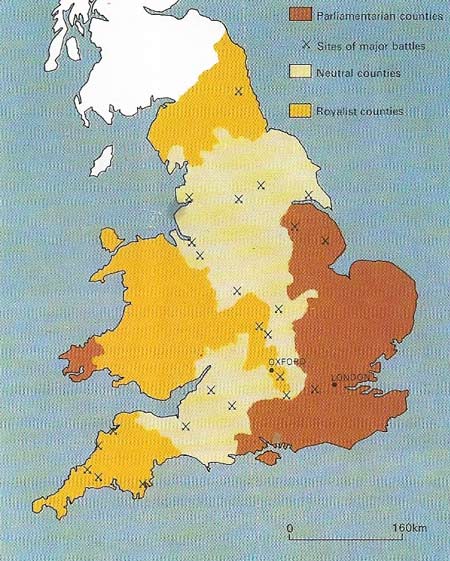

Figure 2. In the first civil war the Royalists were strongest in areas remote from London in the north and west, while the Parliamentarians kept the capital and the populous southeast. Fighting followed for control of divided areas.

Figure 3. The end of press censorship in 1642 brought a flood of pamphleteering and debate. All traditional ideas were opened to discussion and argument. Before long, moderates on the Parliamentary side called for caution in reform, stressing the Aristotelian "golden mean". They warned of the "new extreme" among radical political and religious groups as much as the "old extreme" of the enemy.

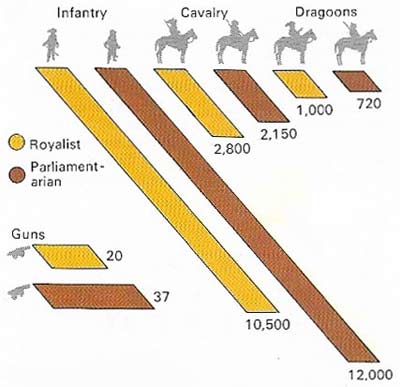

Figure 4. Edgehill (23 Oct 1642) was the first major battle of the civil war and the majority of officers and soldiers were in action for the first time. The two armies were fairly matched and in military terms the outcome was indecisive. By the end of the war, the king’s forces were only a little more than half those of Parliament. The king marched south to set up his capital in Oxford, as London eluded him.

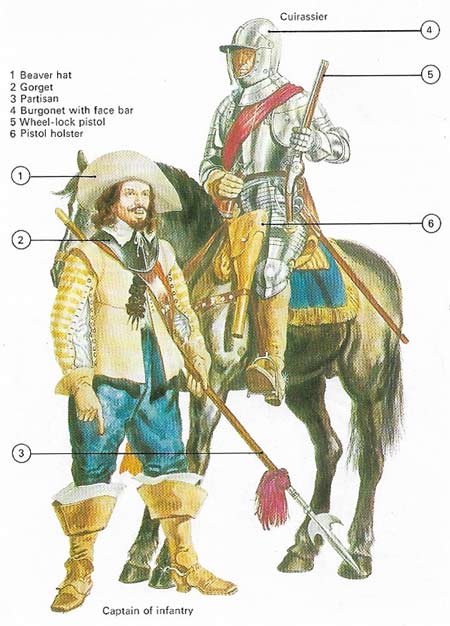

Figure 5. Officers wore civilian garb, whereas troopers on both sides wore some armor.

Figure 6. The restored monarchy in 1660 was much weakened and power was shared with Parliament. The "Cavalier Parliament" was opened amid much state pageantry on 22 April 1661 with Charles II riding in procession from the Tower of London. The landowning gentry had learned to fear a powerful monarchy and standing armies, and they soon became critical of Charles and his ministers.

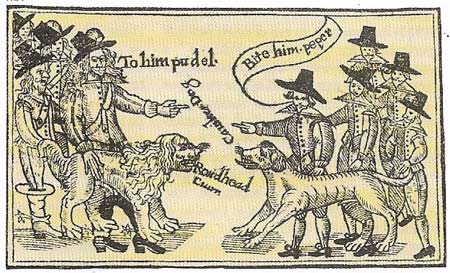

Figure 7. The civil wars marked a breakdown in ordered political and social life and animosities heightened during the course of the fighting. There were not only political and religious divisions between the Royalists and Parliamentarians in 1642, but also social ones. The Royalists were satirized as courtiers and rakes; the Parliamentarians as low-born moralists. The Royalists drew support from some of the gentry and most of the peerage, who often wore lavish costume and long hair, denoting them as men of social standing and wealth. The Parliamentarians also had considerable backing among landowners, but they derived additional support from urban merchants, tradesmen and artisans, who were often motivated by Puritan zeal and wore shorter hair and sober clothing.

The English revolution (1640–1660) was the first of the modern revolutions and it compares closely in many ways with the later French and Russian revolutions. Each political revolution follows its individual and complex pattern of development, but some common stages can be identified.

The revolutionary pattern

These stages include an initial period of political and intellectual excitement, with the collapse of the old regime; the emergence of a radical leadership as the political crisis becomes protracted; an eventual halt to the leftward movement of the revolution; the consolidation of power by a strong-arm and often military-based party and a return towards political stability; and sometimes a formal restoration and a collapse of the revolutionary movement. These stages can be seen in the English, French, and Russian revolutions, with the manifest exception that in Russia there was no restoration of the Romanov dynasty.

The first stage of the English revolution (Figure 2) was the constitutional or "bloodless" revolution of 1640–1641, which weakened the old absolutist regime. It began in November 1640, when Charles I (1600–1649) summoned the Long Parliament to help him out of a financial crisis. Charles, isolated and deeply unpopular, was forced to agree to a wide-ranging set of constitutional reforms that gave Parliament a much more prominent place in the constitution. These changes were accompanied by much political excitement and debate, especially after the ending of press censorship (Figure 3) in July 1641.

|

| The elegant portrait of Charles I by Anthony van Dyck concealed the king's small stature but emphasized his regal dignity and a certain melancholic determination. Van Dyck was appointed official court painter in 1632 by Charles, who was a famous art patron. |

The escalation of the crisis

The second stage saw the revolution move leftward, as the political crisis escalated into civil war. The Long Parliament split into rival parties in the autumn of 1641, the Royalists (Cavaliers) forming a King's party in opposition to the Parliamentarians (Roundheads), who were prepared for further political and religious reforms. Charles attempted unsuccessfully to arrest his main opponents in January 1642 and then fled from London. He thus entered the first civil war (August 1642–April 1646) from a weakened position, because the Parliamentarians held London and the machinery of central government. The Parliamentarians were not, however, able to clinch their dominance until the reorganization of their forces into the disciplined and zealous New Model Army in January 1645. This successfully harnessed militant Puritanism to the Parliamentarian cause. The army, ably directed by Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612–1671), won a decisive victory over the Royalists at Naseby in June 1645.

The third stage marked the apogee of the leftward movement of the revolution. The victorious Parliamentarians themselves split at the time of their success in 1646 and 1647. The more conservative group were the Presbyterians, who, together with the Scots, then allied themselves with Charles. The more radical party, the Independents, backed by Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) and the army, attempted a settlement, failed, and remained hostile to Charles.

|

| Oliver Cromwell was a military genius and a pragmatic politician. He ruled as Protector and tried to reconcile discordant factions, staunchly upholding the principle of religious tolerance. |

The second civil war (February–August 1648) was a brief but bitterly fought contest, which ended with Cromwell's overwhelming defeat of the Scottish army at Preston in August 1648. It was followed by the purge of Parliament (Pride's Purge) in December 1648, the trial and execution of Charles on 30 January 1649, and the abolition of the monarchy and House of Lords in February of that year – a sequence of events that was unprecedented in European history. At the same time Cromwell and the army leadership broke with the lower-class radical political party, known as the Levellers. They pressed for fundamental constitutional changes, implicitly challenging the political and social power of landowning society.

In the autumn of 1647, the Levellers briefly challenged Cromwell for control of the army itself. But Cromwell decided to crush the movement. A Leveller army mutiny was defeated at Burford (Oxfordshire) in May 1649. Deprived of its army base, support for the Levellers rapidly waned. But the difficulty of Cromwell's position – sandwiched between left and right – was accentuated: he was a regicide, as well as the man who had broken the Levellers.

|

| A key development in the 1640s was the growth of the first organized, mainly lower-class political party in English history. This group, known as the Levellers, played an important political role on the years 1647–1649 before eventually being defeated by Cromwell. The Levellers did not have one party leader, but a dominant part was played by "Freeborn John" – the spirited propagandist, John Lilburne (1614–1657), shown here. The Levellers called for a considerable extension of the franchise and were suppressed by both king and Parliament. |

The fourth stage represented the gradual return to political stability. The New Model Army was, in the 1650s, a force of more than 60,000 men. The importance of its power was shown in the brutal suppression of the Irish rebellion (1649–1650) and the routing of a further Royalist uprising (1650–1651).

Cromwell and collapse of army rule

Cromwell proved the most successful ruler (1653–1658) because he was both a skilled politician and a brilliant general. His regime had some foreign policy successes, such as peace with the Dutch in 1654 and victory over Spain (1656–1658), but this system did not last long after his death in 1658. The fifth stage in the revolution therefore saw an initial period of political confusion with the collapse of army rule, followed in due course by the restoration of Charles II (1630–1685) in May 1660 at the invitation of the Convention Parliament. The restored monarchy (Figure 7) was much weaker than it had been previously, and it was the landowning gentry as represented in Parliament who were the ultimate victors of the English revolution, ensuring the permanent end to absolutist monarchy.