Victoria and her statesmen

Fig 1. The Great Exhibition (1851) at the Crystal Palace, asserted Victoria's international standing early in her reign. Rulers from many parts of the world attended the festivities, which were originally conceived by Prince Albert to celebrate the wonders of industry and to promote peace.

Fig 2. Prince Albert (1819-1861), married Victoria in 1840, and rebuilt much of the Kensington district of London for the Great Exhibition. Among the monuments erected to him was the Albert Bridge, shown here.

Fig 3. The death of Albert in 1861 led Victoria to withdraw from social life and dress in mourning for many years. At this point her popularity reached its lowest ebb, but revived by the 1880s. She never recovered from the loss of her German-born husband.

Fig 4. Lord Salisbury was enigmatic and shy and an implacable foe of Irish Home Rule. He made the Conservative Party into the most powerful party in the state by 1902.

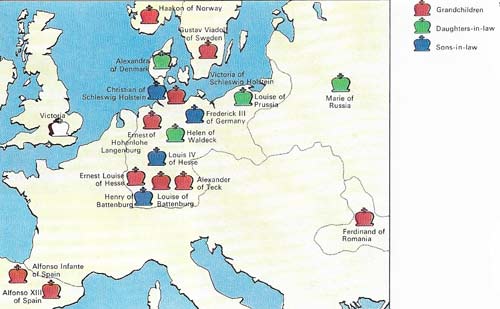

Fig 5. Queen Victoria was related to most of the royal houses of Europe by the marriages of her children and grandchildren. At her death there were 37 of her great-grandchildren living, and she became popularly known as the "grandmother of Europe". Her intimacy with foreign courts gave her a knowledge of diplomacy. But her constitutional position prevented her from exercising real influence over foreign affairs. She was restricted to the Crown's ancient right to be consulted, to encourage and warn.

Fig 6. The queen, as head of state, appointed each new prime minister. Here she is shown giving the seals of office to Lord John Russell (1792–1878) in 1846 after the fall of Peel's ministry on the controversial issue of the repeal of the Corn Laws. In the 18th century, the monarchs chose their own ministers and exercised real discretion over dissolutions of Parliament. Victoria's power was less direct but her personal relations with her prime ministers were of great importance to the history of her reign.

Queen Victoria's reign, from 1837 to 1901, lasted longer than that of any other British monarch. During that time the party system and parliamentary democracy came to their maturity. The monarchy itself moved out of the arena of active politics, but achieved a new status as the neutral guardian of national stability. In 1830 even The Times had found it difficult to mourn the death of George IV; republicanism was a serious radical cry. By 1897, the year of the Diamond Jubilee, republicanism had been drowned in popular royalist enthusiasm.

The changing style of politics

Ten prime ministers served Queen Victoria (Fig 6). None of them was chosen by her in defiance of the wishes of the Commons. Each came to power by virtue of being the leader of his party, and cabinets were composed of members of the same party. That was a marked though gradual change from the eighteenth-century politics of connection. Party had replaced the Crown as the source of political power. After the 1832 Reform Act, both the Whigs and the Conservatives took steps to organize themselves into national parties. Elections lost much local color and acquired national meaning.

The first half of the reign

It was not easy for the 18-year-old princess to step with confidence onto the crowded political stage. Victoria was fortunate to find a devoted tutor in her first prime minister, the debonair Lord Melbourne (1779–1848), then mellowed with age. To the man whom Caroline Ponsonby had flattered to deceive in marriage, Victoria brought a late spring in the autumn of his career. To her, he became as a father.

She was loath to part with Melbourne. But the weakness of her constitutional position was brought home to her by the Conservative victory at the 1841 elections. Loving Melbourne, she had learned to love the Whigs. Losing him, she learned to work as closely and fairly with his successor. Throughout her reign she kept herself fully informed on political developments; her opinions could never be treated lightly by her ministers.

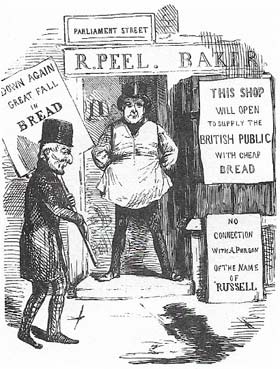

Robert Peel, from 1841 to 1846 the first prime minister of a Conservative (as opposed to a purely Tory) Party, was a new breed of prime minister. His roots were commercial and his forte was economics. He had no sentimental attachment to the landed aristocracy. The squires on the backbenches, the heart of his party, found him uncommunicative and arrogant. He tried to turn the Tories into a party that worked to balance the claims of competing interests, instead of seeking to defend the exclusive interests of the land and the Church. He failed, split his party, and left it a minority for a generation.

|

| Robert Peel (1788–1850) sought an undoctrinaire approach to the problems of industrialisation that brought violent Chartist unrest, and in 1846 after the Irish famine he alienated the traditionally Tory landowners by removing tariffs on imported corn, thus reducing the price of bread. |

Viscount Palmerston (1784–1865) was the beneficiary of this Conservative misfortune. He was prime minister for all but 14 months between 1855 and 1865. England was then enjoying the mid-Victorian boom; the standard of living was generally high and social problems unobtrusive. Palmerston believed that a government did best by doing as little as possible. His great interest was foreign affairs, the one sphere where the royal will still counted for something. He and Victoria clashed often and she sometimes won. In 1857 Palmerston made light of the Indian Mutiny; Victoria knew better, and it was on her initiative that troop reinforcements were sent to India which saved the British presence there.

Gladstone and Disraeli

Palmerston's death in 1865 allowed William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898) to assume the leadership of the Liberal Party. He was the first prime minister to form four governments (1868–1874, 1880–1885, 1886, 1892–1894). He was too single-minded, too earnest, and too radical to earn anything but Victoria's habitual distrust. But he was beyond question the giant of Victorian politicians. Under his premiership the Irish Church was disestablished (1869), secondary education made universal (1870), the secret ballot introduced (1872), and the agricultural laborer enfranchised (1884). His mission, he said, was to pacify Ireland, but his Home Rule Bill of 1886 was defeated by Liberal Unionists, led by Joseph Chamberlain (1836–1914), perhaps the greatest Victorian statesman never to be prime minister.

|

| Gladstone was the son of a Liverpool cotton merchant and retained a radical and evangelical outlook throughout his career. His stirring oratory made him the darling of the industrial masses, but he was a highly intellectual man who was MP for Oxford University (1847–1865). His political career, like that of Disraeli, began in The Conservative Party, in Peel's ministry; but he joined the Liberals in 1859. |

Gladstone's great rival was Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881), already a tired man at the start of his main ministry (1874–1880). His achievement was to help swell the tide of imperial sentiment by his rhetoric and, by making Victoria Empress of India in 1876, to exalt in the popular imagination the person and office of the monarch. And she for six years found in "Dizzy" an unfailingly courteous and amusing companion. He was her favorite prime minister. It was an extraordinary end to the career of one who, from his Jewish descent, his landless status, and suspect literary connections, had never become quite acceptable even to his own Conservative party.

|

| Disraeli became Conservative leader on the Commons on 1849. He passed the 1867 Reform Act in an attempt to outbid the Liberals for popular appeal, and founded the Conservative Central Office (1868) to organize the party on the country. |

His successor as Conservative leader, Lord Salisbury (1830–1903) (Fig 4), was in the purest Tory mold, the last great representative of the Cecil family that had risen to prominence under Elizabeth I. He was the ideal minister to preside over the Jubilee celebrations. He formed three administrations (1885–1886, 1886–1892, 1895–1902), and left politics just after the queen's death.

|

| The Diamond Jubilee of 22 June 1897 was a grand imperial festival which was attended by representatives of Victoria's 387 million subjects. The queen was 78 and suffered from rheumatism and failing eyesight. The short service at St Paul's, which marked the halfway point of the royal procession from Buckingham Palace, was held outside the cathedral to avoid carrying the queen up the steps in a wheelchair. Like the jubilee of 1887 the Diamond Jubilee provided an occasion for a colonial conference. |