Victorian London

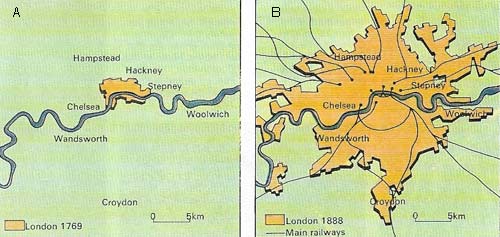

Fig 1. Railways grew out of urban expansion but also created it. The London and Greenwich line, opened in 1836, was London's first steam powered railway. By 1852, most of today's mainline stations were in being and there were several suburban lines. From 1863 the Underground system provided rapid transport in the metropolitan area. In 1880, between 150 and 170 million rail journeys were made in the city annually.

Fig 2. Cholera epidemics in the 1830s and 1840s gave an important stimulus to the public health system. Royal Commissions of inquiry led to the creation of a General Board of Health and a Medical Officer of Health in 1848, in spite of opposition from the City of London. Improvements in water supply and sanitation followed. Until the 1860s, London's sewers were discharged into the Thames.

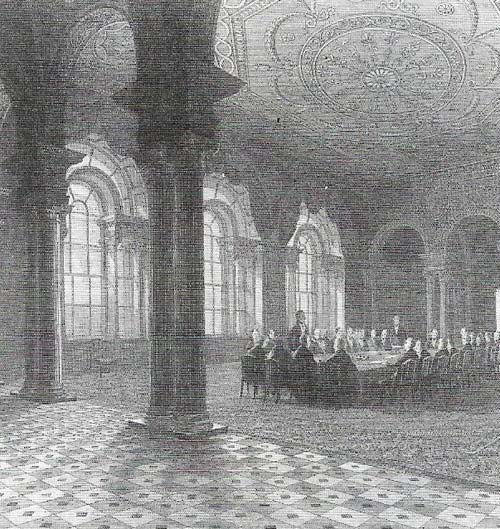

Fig 3. The Bank of England, established in 1694 to finance a war with France, was subsequently granted a monopoly of joint stock banking. While smaller banks were restricted to only six partners between 1708 and 1826, it became government banker and reserve bank for a whole country – a status ratified in the Bank Charter Act (1844). The fine buildings, completed in 1827, are imposing examples of the many public buildings erected in London during the 19th century. Others, in Victorian neo-Gothic style include St Pancras Station (1865–1871) and the Royal Courts of Justice (1871–1882).

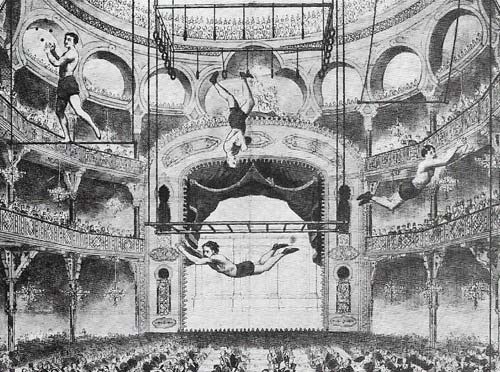

Fig 4. Music halls became immensely popular in the 19th century. After a licensing Act in 1843, music halls, unlike theatres, could serve alcohol. The first commercial halls were the Canterbury in Lambeth (1852) and the Oxford Music Hall in Oxford Street (1861). Forty halls were taking in custom in London in 1868, and as the century progressed, music halls came to be more widely accepted as an alternative to the theater.

Fig 5. The East End of London remained notorious for its poverty and bad housing well into the 20th century. Many of its inhabitants were immigrants who had come from Ireland and continental Europe.

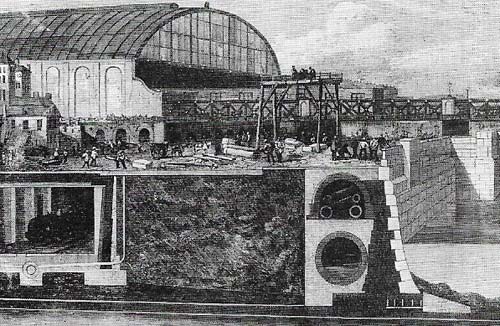

Fig 6. Construction of the Embankment (started 1867) with railways, sewerage and other services was a rare example of unified planning for growth. An efficient London system of drainage and sewerage was delayed by a lack of centralized authority. In 1858, work began on a complete system of sewerage for the capital. This great engineering feat was completed in 1865 and cost £4 million, with 131 km (82 miles) of pipe carrying 1,703 million liters (420 million gallons) of sewage each day.

Fig 7. London was the social center of Britain. The London "season" attracted wealthy families up from the country to reside in the substantial houses they kept in town. Hyde Park (shown here) was a fashionable place of recreation.

In the nineteenth century, London became the biggest and richest city in the world, its population quadrupling to reach 6,586,269 by 1901 in Greater London (a term first used in the 1881 census). Its growth as the heart of a great commercial and military empire presented a spectacle both imposing and appalling. Between the plush and cut-glass elegance of the West End and the fever-ridden slums of Dickensian description lay a gulf the century could not bridge. Overwhelmed by the squalor in which many of the people lived, the critic John Ruskin in 1865 called London "rattling, growling, smoking, stinking – a ghastly heap of fermenting brickwork pouring out poison at every pore".

Commerical expansion

The port of London was central to the economic growth of the capital. The first large enclosed docks were completed in 1802. In 1885 the expansion of trade was marked by the completion of the Victoria Dock, 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) long. Although challenged by ports such as Hull and Liverpool, London remained the premier port, and 13 million tons of goods passed through it in 1880.

London was the center of a host of industries associated with trade, refining and processing imported goods for distribution to the rest of the country or for re-export. In addition to brewing, distilling, tanning, and food-processing the capital supported a shipbuilding industry that was overtaken by Newcastle and Glasgow only in the closing years of the century. By 1851 there were almost half a million workers engaged in manufacturing. Service industries employed nearly one million by 1861.

Even before the end of the eighteenth century, London had begun spreading out into rural areas of Surrey and Kent. The nineteenth century saw a rapid extension of this process as the City proper, the "square mile" formerly confined by the city wall, was given over to shops, offices, and warehouses. In the West End, fashionable squares and town houses were completed. The growing middle classes built houses in suburbs such as Camberwell, Paddington,and Clapham. Although the East End (Fig 5), including Whitechapel, Bethnal Green, and Stepney, continued to grow, the working classes too began moving to districts on the edge of the built-up area, such as Hammersmith.

Railways and transport

The growth of suburban London was greatly accelerated by the coming of the railways (Fig 1), which soon spread out into a dense network. The first underground line in the world, from Paddington to Fenchurch Street, was opened by the Metropolitan Railway Company in 1863 and in the first six weeks carried an average of 26,000 passengers a day. A first-class fare between Edgware Road and King's Cross was sixpence. In 1864 special workmen's trains were introduced with a maximum return fare of only threepence. Other lines soon connected the main line stations and all-important parts of the metropolis. The first electrified line opened in 1890. By the end of the century horse-drawn buses and trams provided alternative transport.

|

| St Paul's Cathedral, erected in more spacious days, looks down on the Fleet Street of 1900 when vehicles thronged London's streets and traffic jams had become common. In 1850 there were more than 1,000 horse-drawn buses at work in the capital as well as countless carts and wagons. Congestion was one indication of the need for a new form of urban planning. London was the first industrial metropolis to have to cope with the problems of public health, urban transport, housing and other services on a mass scale. The unprecedented difficulties created by its growth necessitated a dramatic increase in the powers of local government. |

The central area of the capital was refurnished with a series of new public buildings, including the rebuilt Houses of Parliament (1836–1867), the Royal Courts (1871–1882), the Bank of England (1795–1827) (Fig 3) and the great museums in Kensington. Trafalgar Square was completed in the 1840s. Widened streets, notably the Embankment, imitated the boulevards of Paris and some of the old slums were cleared to make way for new streets such as Charing Cross Road. Sewerage (Fig 6), lighting, paving and water supply were gradually brought under control after the cholera epidemics of the 1830s and 1840s. The establishment of a Metropolitan Board of Works in 1855 was important for unified planning.

Social reforms

The vitality and commercial prosperity of the capital were reflected only slowly in social reforms. As people crowded into the terrace houses thrown up by speculative builders around gasworks, breweries or warehouses, the parishes of the East End became spawning grounds for crime and disease. General William Booth (1829–1912), who founded the Salvation Army in 1878 to reconvert the slum dwellers called them the people of "darkest England". In that year, while many landowners were earning £100,000 a year and paying tax of only 2d in the pound, the average laborer's income was £70. Fashionable strollers wore hand-sewn garments created by sweated labor paid at a rate of only 2d an hour.

|

| London fashion set the pattern of taste and consumption for the country as a whole. The mass market in the capital stimulated the rise of large department stores in the 1880s along bustling streets such as Regent Street, shown here. During the 19th century small, family run shops began to disappear. They either developed as chain stores, such as J. Sainsbury's, which first opened in Drury Lane in 1869, or they were replaced by large, independent department stores. |

In 1885, it was estimated that one in four Londoners still lived in abject poverty. Only after 1880, when primary education became compulsory, were the streets cleared of ragged children living on their wits.

Despite the ferocious penalties for even petty crime, an estimated 100,000 in London lived by thieving or swindling in the 1860s, and another 80,000 were prostitutes. Sensational stories of crime and capture by the Metropolitan Police Force could be read daily in the "penny dreadfuls". This was the fog-shrouded city of Sweeny Todd the Barber and Jack the Ripper. Violent riots by the unemployed in 1886 and 1887 gave belated vent to the distress that went hand-in-hand with the music halls (6), gin palaces, and imperial pomp of Victorian London.

|

| A professional police force for London was created under the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829. Until then, London had only a few hundred professional police. The security of the capital largely depended upon an uncoordinated band of watchmen and constables under several different authorities. The Act enabled a unified policing of the whole metropolitan area, with the exception of the City proper, using several thousand professional police officers. |