causes of World War I

Figure 1. The British fleet in the 1890s aimed to equal those of the two next biggest naval powers, France and Russia. When this two-power standard was challenged by the rise of the German navy in the 1900s, Britain settled her differences with France and Russia and concentrated on maintaining naval superiority over Germany. As a result, Anglo-German relations became increasingly embittered. The launching of the Dreadnaught (a faster and better armed than any ship before it) by Britain in 1906 open a new stage in naval rivalry as each country tried to build more such vessels than its neighbours. But Britain kept its lead.

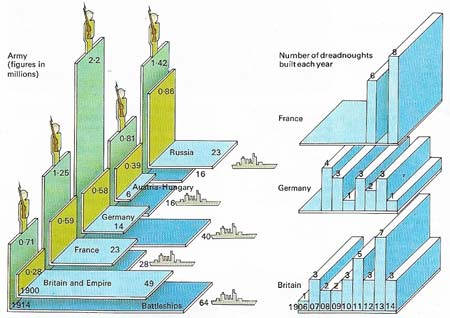

Figure 2. An armaments race between the Great Powers before 1914 both reflected and heightened European tension. In addition to building a large navy, Germany possessed the most formidable army in Europe. Although its size remained fairly stable from 1900–1910, Germany's deteriorating diplomatic situation led in 1912–1913 to increases in army strength which provoked the other Great Powers, except Britain (the only one with a volunteer army) to increase their own forces.

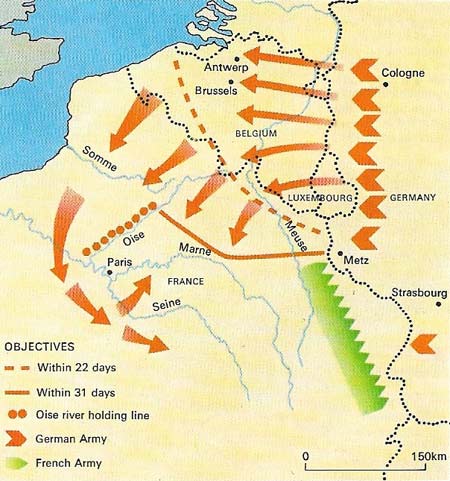

Figure 3. The Schlieffen Plan was based on a two-front war with Russia and France, which had been allies since 1894. It provided for a massive German assault through Holland (later excluded) and Belgium to outflank the French army. Meanwhile, Austro-German forces would defend the east until the main German army, having knocked out France, could be rapidly moved to meet the slowly advancing Russians. Violation of Belgian neutrality would risk British intervention.

Figure 4. A wartime photograph of the Kaiser (center) and his generals reflects his fondness for military life. Responsible for Germany's foreign policy, the ultimate decision to mobilize on 1 August was his alone.

Figure 5.Gavrilo Princip (1893–1918) precipitated the chain of events leading to war when he shot the heir to the Austro-Hungarian thrones, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife while the were visiting Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia, on 18 June 1914. He was one of a group of Bosnian conspirators with Serbian support.

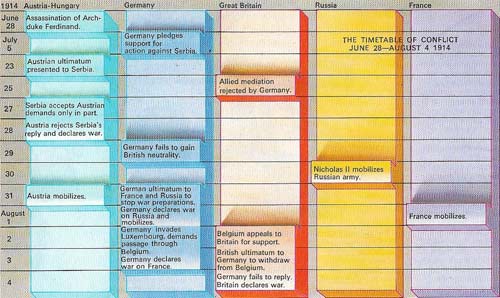

Figure 6. Events leading to World War I.

Figure 7. High-spirited French soldiers marching to the front after the outbreak of war in August 1914 typified the enthusiasm of all the belligerent countries, based on intense nationalism and a belief that the war would be short and glorious.

During the 1890s Germany's ruling class, headed by the intelligent but vacillating German Kaiser, Wilhelm II (1859–1941), abandoned Bismarck's cautious foreign policy in favor of a more dynamic one designed to reflect Germany's industrial and military strength. Germany wanted a large colonial empire, not only for economic reasons but to enhance its prestige. To this end a law to expand the German navy, the first of many such laws, was enacted in 1898. The new navy was designed ultimately to challenge British naval supremacy (Fig 1) and to force Britain, faced with seemingly perpetual Franco-Russian hostility, to collaborate in a wholesale reallocation of colonial territory.

German diplomatic setbacks

The first setback to Germany's "world policy" came in 1904 when Britain and France settled their colonial differences. Then, in 1907, Britain resolved its long-standing central Asian disputes with Russia, France's ally since 1894. In 1905 Germany, taking advantage of Russia's defeat by Japan, challenged France's increasing strength in Morocco and coerced it into participating in an international conference in January 1906 at Algeciras to settle the Moroccan question on Germany's terms. However, Germany suffered a diplomatic defeat, for its plans for Morocco were supported only by Austria-Hungary. Moreover Germany's assumption that the Anglo-French entente would be wrecked by Britain's failure to support France proved to be similarly erroneous. Britain cooperated closely with France during the conference and, alarmed by Germany's aggressive policy, initiated unofficial Anglo-French military discussions.

|

| Visiting Tangier in March 1905, the Kaiser pledged to uphold Morocco's independence. He hoped to protect German interests in Morocco (rapidly falling under French control) and to force France to recognise that it's future lay in alliance with Germany. While the independence of Morocco was thus preserved until 1911, Germany's clumsy diplomacy drove France and Britain closer together. |

Germany next proceeded to alienate Russia. In 1909 it insisted with a veiled threat of war that Russia recognize Austria-Hungary's 1908 annexation of Turkish Bosnia-Hercegovina and abandon support for Serbia's claim for compensation. International tension was further increased when, in a bid to secure colonial compensation from France, now almost in control of Morocco, Germany sent a gunboat to the Moroccan port of Agadir on 1 July 1911. Although during the following months Britain and France came close to war with Germany over the Moroccan issue, a Franco-German colonial compromise was signed in November. The crisis left a legacy of bitterness and hatred in both countries. As a result Germany, in 1912, further increased its naval strength and began to expand its army. It was followed inevitably in this action by every other Continental great power (Figure 2).

Instability in the Balkans

The causes of World War I were, however, more directly connected with events in the Balkans. In 1912 the Balkan League (Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Bulgaria) drove Turkey out of most of its remaining possessions. The following year Bulgaria was defeated by its former allies, Greece and Serbia, and lost its Macedonian gains of 1912 to Serbia. Austria-Hungary was thus faced with a greatly enlarged and ambitious Serbia, determined that the Slays within the Hapsburg Empire should come under this rule.

The cumulative effect of all these crises was to increase preparations for war: indeed, Germany had long since devised its blueprint for victory, perfected by Count Alfred von Schlieffen (1833–1913), Chief of Staff, in 1905, and amended by his successor, Helmuth von Moltke (1848–1916). The Schlieffen Plan (Figure 3) relied on the slowness of Russian mobilization and provided for a rapid thrust through Belgium to defeat France, leaving the German army free to move rapidly east to meet the Russians.

The assassination of the heir to the Hapsburg throne, Franz Ferdinand (1863–1914), at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 (Figure 5) was the climax of a series of Serbian provocations towards Austria. Berlin feared that if Austria-Hungary failed to take the opportunity provided by the murder to bring Serbia within its orbit, its multinational empire would collapse leaving Germany isolated. Thus Austria was under German pressure to act against Serbia, with the promise of German military support should war ensue. Successive German diplomatic defeats, a sense of "encirclement" by Britain, France and an increasingly strong Russia, and deep divisions within German society all combined in 1914 to convince the German ruling elite of the desirability of war partly to preserve the idea of a German-dominated "Mittel Europe". Although apprehensive, German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856–1921) gambled on both Russian and British neutrality and hoped that the Austro-Serbian dispute could be localized, in spite of the rigid system of alliances that divided Europe.

|

| Germany's Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg (left) and Foreign Minister Gottlieb von Jagow (1863–1935) misjudged the willingness of Britain to go to war over a "scrap of paper" guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium. They gambled on diplomatic victory for the Central Powers when, with the promise of German military support, they encouraged Austrian action against Serbia in July 1914. |

The final steps to war

Austria finally presented an ultimatum demanding the right to investigate Serbian terrorists and, when Serbia rejected this, declared war on 28 July 1914. Russia could hardly stand aside and, faced with growing pro-Slav feeling, Tsar Nicholas II (1868–1918) ordered mobilization. British mediation failed to persuade Austria-Germany to compromise. When France refused to leave Russia to fight alone, the Schlieffen Plan was activated and events proceeded rapidly (Figure 7) towards war between the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey) and the Allies (Russia, Serbia, France, Belgium and Great Britain).

|

| Count Leopoldo von Berchtold (1863–1942), the Austrian Foreign Minister, was convinced that the multinational Hapsburg Empire would collapse unless Serbia was crushed. His opportunity was provided when Franz Ferdinand was murdered but although promised full German support, he encountered considerable opposition to his plans from the Hungarian government. This partly accounted for the delay in presenting the Austrian ultimatum to Serbia. |