bagpipes

Figure 1. Great Highland bagpipes.

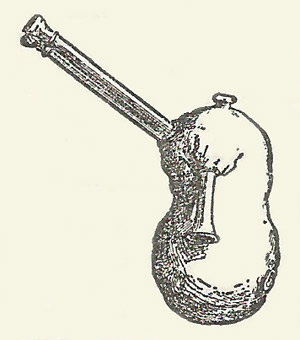

Figure 2. Ancient Roman bagpipe (utricularium). It survived as the Zampagna of the Ambruzzi peasants.

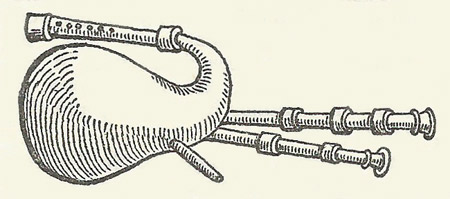

Figure 3. Old German bagpipe. From Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch, Wittemberg, 1528.

The principle of the bagpipes is straightforward: instead of the player blowing directly on a reed pipe, the air is supplied from a reservoir, usually made of animal skin, which is inflated either by mouth or by bellows. The result is the ability to produce a continuous tone, and the possibility of adding extra reed-pipes to enable a single player to make homophonic music. The compass of nearly all bagpipes is limited to one octave but on some types a second octave can be obtained.

History of the bagpipes

The early history of bagpipes is obscure, although forms of it have existed for at least 3,000 years (Figure 2). Because they were made of perishable materials, no early examples survive, and as they have been regarded in recent years as something of a peasant instrument they have not been much documented (except for the Scottish Great Highland bagpipe, which is just one of the wide range and by no means the earliest).

Playing a melody against a drone, and achieving a continuous tone by circular breathing, have been common among reed-pipe players for millennia; so plugging the reed-pipes into a bag was a logical development. Bagpipes can be seen in the art of the Middle Ages, and there is evidence that they were in use at least 1,000 years before that.

Construction

The basic components of a bagpipe are:

Variable characteristics are (i) the source of wind-supply to the reservoir may be either the mouth of the performer or a small bellows held under the arm and by it contracted and expanded. (ii) The chanter from which the various notes of the tune are obtained by means of a series of holes or keys may, or may not, be accompanied by one or more other reed-pipes each confined to a single note (drones), these being tuned to the tonic or tonic and dominant of the key of the instrument. (iii) The reed may be either single, like that of the clarinet family, or double like that of the oboe family; in practice the chanter reed is usually double, while the drone reeds vary in different types of instrument.

Great Highland bagpipe

The world's best-known bagpipe – largely because of its use in the British army and the former Empire – is Scotland's Great Highland bagpipe (Figure 1). In fact, this is just about the only bagpipe to have had substantial military use. Quite similar to the gaitas of Spain's Galicia and Asturias and northern Portugal, it is mouth-blown with a single nine-holed, conical-bored chanter. Today's standardized version has three separate drone pipes: two tenors an octave below the chanter's keynote, and a bass an octave below them.

Pitch

The exact pitch of the keynote varies; while called A, it is generally between B♭ and B. Until recently, Highland pipes were not played with other instruments with a defined scale, so, as with many bagpipes, their overall pitching and tempering of the notes within the scale depended on the ear and satisfaction of the maker and player. Nowadays pipes made for playing alone or in pipe bands still use the exciting non-equal-temperament intervals, but there now exist pipes with their pitch and scale modified to blend better with the wider instrumentation of the Scottish folk-music revival.

Highland pipe music

It is a convention that Highland pipe tunes are written down as if the keynote was A, but with no key signature shown; F and C are read as sharps. The chanter's total range is an octave, plus one tone below the keynote made by closing the bottom hole with the little finger. No overblowing to the next octave is possible.

The music of the Highland pipe falls into two categories: the solo music called in Gaelic ceòl mór ('big music'), also known as piobaireachd ('pipbrock') consisting of a theme and variations, and the more familiar dance and other music, called in Gaelic ceòl beag ('small music'). As with other unstopped chanters, notes are separated and tunes given style and impetus by rapid finger-flicking grace notes.

Bagpipes of the British Isles

Scotland has other bagpipes, including the bellows-blown small-pipes, reel-pipes and lowland or border pipes, but south of the border, most of England's bagpipes (and also the Welsh pibcwd) had died out until recent revivals.

The exception to this is in Northumberland, where there have long been skilled players of the quiet, reedy-sounding Northumberland small-pipes. These are bellows-blown, and their chanter – usually equipped with keys and so able to play chromatically – has a stopped end, so that by closing all the finger holes it can be silenced between notes, producing a characteristic staccato style.

The end of the chanter of the Irish uilleann pipes, also bellows-blown, can be pressed on the player's thigh to close it, and it can be overblown into the second octave. The uilleann pipes are extremely highly developed; the bunch of drones that lies across the player's knees includes some closed-ended ones known as regulators, fit with keys that allow them to be switched on and off during play to give a chordal accompaniment.

Iberian bagpipes

Most countries of Europe and some beyond have at least one distinctive type of bagpipe. The gaitas of Spain's Galicia and Asturias have recently experienced a renaissance. Iberia has other pipes, too, including the gaita de foles of Portugal's Tras-os-Montes, the sac de gemecs of Catalunya, Mallorcan xeremies, and the gaitas of Aragon and Zamora.

French and Italian bagpipes

France has an array of regional pipes, including the high-pitched Breton biniou, the chabrettes of Limousin, Berry, and Bourbonnais, Auvergne cabrette, Gascon boha, the Grande Cornemuse Bourbonnais (often played with hurdy-gurdy), and the musette, a small bellows-blown pipe with four drones, whose bores are all folded into a single stubby cylinder.

Italy has even more, among them the gran zampogna, one of the world's largest, the widespread zampogna di Scapoli which is often played together with the shawm piffero, and in Calabria about five forms of ciaramedda.

For Western European pipes the double-bladed reed is the norm, in a chanter with usually a single, often conical bore, but most of the other bagpipes of the world have single-bladed chanter reeds, and often have two or more usually parallel bores in the chanter, like the bagless reed-pipes from which it is likely they are derived.

Balkan bagpipes

The Balkans and surrounding countries are rich with bagpipes. Bulgaria has two main forms – the gaida and kaba ('big') gaida, both with a single-blade reed in a single-bore chanter – which are central to the sound of the country's highly sophisticated traditional music. Romania's cimpoi is similar in design. In neighboring Macedonia there is a saying: 'without the gajda there is no wedding'.

Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia have a wide range, including the double-chantered mih (whose bag in the Herzegovinian form features claws at the skin's leg-apertures), the robust gajde with its curved, bell-ended double chanter, and the duda, which can have triple or even quadruple chanter bores.

Greek pipes include the Thracian gaida and the double-chantered Dodecanese tsambouna. To the north can be found the double-chantered Hungarian duda and Slovak gajdy, on into Belarus for the duda, Russia for the volynka, then Lithuania's minu ragelis, Latvian dudas, Estonian torupill, and Swedish sackpipa.

A world of pipes

Names such as the bock of Bohemia (a complex form with a folded bass drone like the Polish duda), the koza duda of Ukraine and koziol and triple-chantered koza of Poland refer to the goat, which often supplies the skin. In eastern and central European pipes, an effigy of its horned head is commonly carved at the top of the chanter, whose stock is tied into the goatskin's neck opening while the blow-pipe and drone stocks occupy its leg apertures.

To the east and south, the Laz people of the Turkish shore of the Black Sea have the tulum, whose double chanter consists of canes set into a wooden yoke, showing very clearly the reed-pipe connection, as does the Tunisian mezoued, which has two, five-holed unison-tuned hornpipes tied into a droneless bag with claws like the Herzegovinian mih. The Berbers have the ghaita, Azerbaijan has the balaban, Iran the ney-anbhan. India's shruti has been largely supplanted by Scottish Highland bagpipes, many of them made in neighboring Pakistan.