COULD YOU EVER DIG A HOLE TO CHINA?: 3. Scratching the Surface

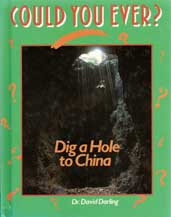

Figure 1. For thousands of years, people have entered the Earth's interior through caves such as this one on the Malaysian island of Sarawak.

Figure 2. Aragonite Alcove in Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico, is known for its icicle-like stalactites and stalagmites. These are slowly formed from drops of calcium carbonate.

Figure 3. Texas blind salamander: an animal that lives in caves in permanent darkness.

Figure 4. Commuters board a subway in a Washington, D.C., metro station.

Figure 5. Composition of the Earth's crust.

There are two ways to go down into the crust. You can dig your own hole, or use one that nature has already provided. Caves in many parts of the world offer the chance to explore a fantastic, silent realm beneath the surface. This is the realm of weird rock formations, of beautiful crystals, and of strange creatures that have never seen the light of day. Caves provided the first means by which human beings could enter the interior of their planet.

Because of the endless movement of different parts of the Earth's crust, some places that were once covered by ocean have been lifted up to form land. This explains why fossils of sea creatures can often be found in rocks hundreds of miles from the nearest shore. These creatures died millions of years ago. At that time, the Earth's oceans and continents were arranged quite differently than they are today.

Most of the animals and plants that died in the sea long ago are not well preserved as fossils. Instead, their bodies were completely crushed as layer upon layer of other remains, or sediment, piled up on top of them. Gradually, the broken shells and skeletons of the dead creatures turned into rock. One common rock that formed in this way is LIMESTONE.

The Story of Caves

The great earth movements that raised up the limestone from ancient seabeds also caused it to crack. Rainwater could trickle down into the cracks and easily work its way deep below the surface. But first, the rain had to soak its way through layers of soil above the limestone. In doing so, it mixed with carbon dioxide, a gas produced by dead and decaying plants. Carbon dioxide picked up from the soil, and also from the air, turns pure rainwater into a weak acid known as carbonic acid.

As rainwater penetrated the limestone cracks, the acid in it dissolved the limestone and carried it away. Over many thousands of years, the cracks grew wider and wider, until they became caves.

In every state in the United States and in many countries around the world, there are caves that were created in this way. Some, like Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico and Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, have sections that have been made safe for anyone to visit. The part of Mammoth Cave that is open to the public is just the start of a huge series of passageways and caverns that is known to extend for more than 330 miles. That makes it the longest in the world. But although caves may be very long, they do not penetrate very deeply into the Earth. In fact, the deepest known point in any natural cave is just 5,036 feet – less than a mile beneath the surface.

Life Underground

Caves may seem unlikely homes for animals and plants but, in fact, they are inhabited by a wide range of species. Some creatures, such as the insect-eating bats of Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, spend only part of their time underground. Other species have become so well adapted to living below the surface in complete darkness that they could not survive on the surface. These permanent cave dwellers are called troglobites.

Because troglobites live where there is absolutely no light, they have no need of eyes. Instead, they find their way mainly by feel and smell. They also lack any pigment, or skin coloring. In surface-dwelling species, such pigment helps block out harmful rays from the Sun. As a result, troglobites are either white or, if their blood shows through their skin, pale pink.

Blind cave fish, salamanders, crayfish, spiders, mites, and certain kinds of insects are among the animals found underground. All of these species have some features in common with their relatives that live on the surface. But they have also adapted in special ways. Most insects, for instance, have amazingly long feelers which they use for tracking down prey in the dark.

Tunnels and Subways

Nature takes many thousands of years to wear away rock to form caves. But today, human beings can dig tunnels, miles in length, at a far greater speed.

As early as the mid-nineteenth century, some cities were becoming so crowded that plans were made to build underground railways. The first one to open was the Metropolitan Line in London in 1863. Today, the London Underground is the largest subway system in the world. At its deepest point, it is 102 feet below street level.

To begin with, subway tunnels were built by "cut and cover" methods. This involved digging a trench along the street, lining it with brick, and then covering it with brick arches or girders to make a roof. Later, tunnels were bored through the ground by workers using spades and pickaxes, and then lined with cast iron.

In recent years, giant machines have replaced most human labor. Many major underground projects now use tunnel-boring machines, or TBMs, equipped with rotating cutting teeth. As the rock breaks up at the front of the TBM, it is carried away on conveyor belts to be loaded onto waiting trucks or trains.

The world's longest undersea tunnel is the Channel Tunnel, which runs 130 feet beneath the English Channel and extends 23½ miles between Dover in England and Calais in France. Giant TBMs, 886 feet long with cutting heads 15.7 feet wide, bored through the soft chalk at a rate of five-eighths of a mile a month to make the Channel Tunnel, which now allows high-speed trains to travel between London and Paris in just three hours.

Riches of the Earth

Humans dig holes for many reasons other than underground transport. Mining is one of the most important of these. The Earth is a vast storehouse of energy and minerals. It can provide us with everything from fuel for warmth to metals and chemicals for industry.

Around 300 million years ago, large areas of the land were covered by steamy swamps where giant, fernlike plants and other strange vegetation grew. As these plants died, they were buried deeper and deeper below the surface. Gradually, they turned into hard, black coal. Burned as a fuel in homes and power stations today, coal is what remains of vast forests that existed on Earth before the age of dinosaurs.

In addition to coal, our planet holds huge stocks of various metals. Iron, for instance, makes up about a twentieth of the Earth's crust and is mined in large quantities. Like most metals, it is not found in a pure state but as an ore, combined with other substances from which it must be separated. Aluminum ore, known as bauxite, and copper ores are also heavily mined for industrial use.

To find ores and other useful substances in the Earth, prospectors set off underground explosions which send shock waves through the surrounding rock and soil. These waves pass through different materials at different speeds. They are also deflected in various ways. The echoes are picked up by microphones on the surface. Scientists use this information to construct a picture of the types of rock, soil, and minerals in that area. If this type of survey shows that minerals are present in large amounts, mining companies will set up the machinery to extract them.

Down the Mines

The way in which coal and most minerals are removed from the ground depends on the size, shape, and location of the deposit. When minerals lie close to the surface, workers remove the vegetation and top layers of soil and rock, called the overburden, so that the ore can be dug out. This method is known as open pit mining. Since the work is all above ground, huge excavators on crawler tracks and other heavy vehicles are used. Such mining methods, though, can cause severe damage to the area where they tear up the soil.

Deep mining is far more difficult, dangerous, and expensive. Shafts, tunnels, lighting, ventilation, and water pumps are all necessary parts of the operation. Once a shaft has been dug, timber, steel, or concrete pillars are used to support the rock and protect the workers. Finally, the ore or rock at the exposed face has to be broken down into small chunks so that it can be moved to the surface.

The depth of mines varies greatly. Deepest of all is the Western Deep Levels gold mine in Carltonville, South Africa. There miners work as far as 12,394 feet, or almost two and a half miles, below the surface. This is the deepest that human beings have ever descended into the Earth. Even though the bottom of the Western Deep Levels mine is much less than a thousandth of the way to the center of the Earth, the conditions inside it are uncomfortable. The pressure of the layers of rock above is tremendous and miners must work in temperatures as high as 131°F. Still, mines are far from being the deepest of holes made by human beings.