anthropology

Cranium of Australopithecus sediba. Photo credit: Wits University.

Figure 1. Various branches of anthropology (red) and their links with allied sciences (yellow).

Figure 2. Australopithecus afarensis skull.

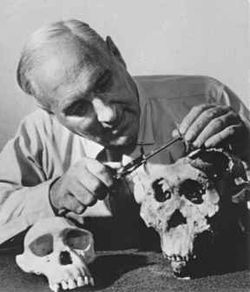

Figure 3. Louis Leakey.

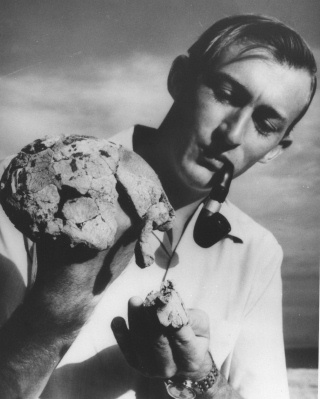

Figure 4. Richard Leakey.

Figure 5. Neanderthal skull.

Anthropology is the study of humankind from biological, cultural, and social viewpoints (Figure 1). Herodotus may perhaps be called the father of anthropology, but it was not until the 14th or 15th centuries, with the mercantilist expansions of the Old World into new regions, that contact with other peoples kindled a scientific interest in the subject. In the modern age there are two main disciplines, physical anthropology and cultural anthropology, the latter embracing social anthropology.

Physical anthropology

Physical anthropology is the study of humankind as a biological species, its past evolution and its contemporary physical characteristics. In its study of prehistoric man it has many links with archaeology, the difference being that anthropology is concerned with the remains of human fossils while archaeology is concerned with the remains of human material culture. The physical anthropologist studies also the difference between races and groups, relying to a great extent on techniques of anthropometry and, more recently, genetic studies.

Cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is divided into several categories. Ethnography is the study of the culture of a single group, either primitive or civilized. Fieldwork is the key to ethnographical studies, which are themselves the key to cultural anthropology. Ethnology is the comparative study of the cultures of two or more groups. Cultural anthropology is also concerned with cultures of the past, and the borderline in this case between it and archaeology is vague. Social anthropology is concerned primarily with social relationships and their significance and consequences in primitive societies. In recent years its field has been extended to cover more civilized societies.

Glossary

Australopithecine

Any member of a species of the genus Australopithecus (Figure 2). Australopithecines lived during the Pliocene and early Pleistocene geological epochs in Africa (i.e., about 4.2–1.2 million years ago). Australopithecines and humans are hominids. One or more species of australopithecines probably were our ancestors.

Cro-Magnon Man

A race of primitive man named for Cro-Magnon, France, dating from the Upper Paleolithic and usually regarded as Aurignacian, though possibly more recent. Coming later than Neanderthal Man, Cro-Magnon Man was dilichocephalic (see cephalic index) with a high forehead and a large brain capacity, his face rather short and wide. H was probably around 1.7 m tall, powerfully muscled and robust.

Hominid

Any primate in the human family, Hominidae. It includes all members of the genus Homo of which Homo sapiens is the only living representative. Australopithecus is an extinct genus.

Hominoid is the collective term for hominids and apes. Together with monkeys, hominoids constitute the anthropoid primates.

Homo

The genus to which humans belong. Modern humans are classified as Homo sapiens sapiens.

Homo erectus

A species of early human dating from about 1.5 million to 0.2 million years ago. The "Ape Man of Java" was the first early human fossil to be found, late in the nineteenth century. Both it and Peking Man, another early discovery, represent more advanced forms of Homo erectus than older fossils found more recently in Africa.

Homo habilis

A species of early human discovered by Louis Leakey in 1964 in the Olduvai Gorge, East Africa. Its fossil remains have been estimated to be between 1.8 and 1.2 million years old, being contemporary with Australopithecus. The development of hand and skull is much more like that of modern humans.

Leakey, Louis Seymour Bazett (1903–1972)

Kenyan paleoanthropologist and archeologist (Fig 3). Leakey and his wife Mary (1913–1972), conducted important research on human evolution. Many of their most important discoveries were made in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. Here, they unearthed (1959) a hominid fossil Zinjanthropus or Australopithecus bosei about 1.75 million years old, and found (1964) the remains of Homo habilis – thought to be a direct ancestor of Homo sapiens sapiens. Leakey proposed the "Out of Africa" model of human development. After his death, Mary and their son, Richard Leakey, continued to make important finds.

Leakey, Richard Erskine Frere (1944–2022)

Kenyan paleoanthropologist and archeologist, son of Mary and Louis Leakey (Figure 4). In 1972, at Lake Turkana, Kenya, Leakey discovered a 1.9 million-year-old skull of Homo habilis. Other discoveries include a Homo erectus skeleton about 1.6 million years old. After serving as head of the Kenyan National Museum, Leakey became director of the Kenyan Wildlife Service (1988–1994).

Neanderthal

A member of the most well known species of late archaic Homo sapiens (Figure 5). Neanderthals lived mostly in Europe and the Near East from 150,000 years ago or even earlier until at sometime after 28,000 years ago. There is an on-going debate as to whether they should be considered Homo sapiens or a distinct but related species. If they were members of our species, they were a different variety or race (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis). On the other hand, if they were different enough to be a distinct species, they should be considered to be Homo neanderthalensis.