what will happen when Betelgeuse explodes?

Figure 1. Artist's impression of an Earth-like planet about to be destroyed by a nearby supernova explosion. Credit: Jeff Darling.

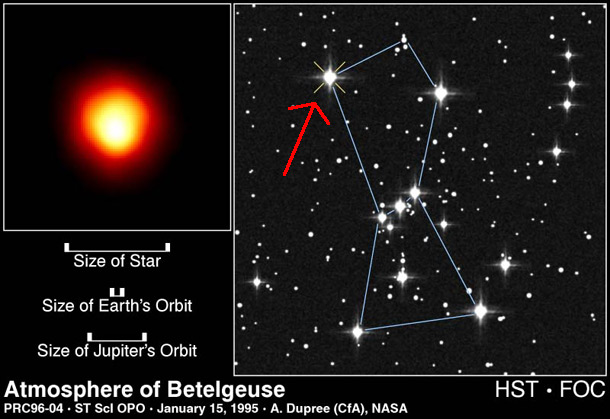

Figure 2. Betelgeuse: its appearance (as imaged by Hubble), size, and location.

Find the constellation of Orion and you'll soon spot Betelgeuse, the brilliant orange star that marks the eastern shoulder of the Great Hunter. Its color stems from the fact that it's a cool, red supergiant, one of the largest and brightest stars in our neck of the Galaxy. Put in place of the Sun, Betelgeuse would swallow up the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, and reach out almost as far as Jupiter. Although only about 10 million years old (compared with the Sun's age of 5 billion years), Betelgeuse is already senile thanks to its great mass – at least 15 times that of the Sun.

Massive stars have a lot more nuclear fuel (mainly hydrogen) than their lighter-weight cousins, but they race through this fuel supply many times faster because their cores, where most of the energy production takes place, are so much denser and hotter. When the central hydrogen is gone, the star continues to make light and heat by "burning" (through nuclear fusion) helium, then successively heavier elements, all the way up to iron. But when the stellar core is clogged with iron, the star runs out of options. It takes more energy to fuse iron nuclei than is released in the fusion process.

With the core shut down, there's no longer a strong outward push of radiation to balance the inward force of the star's own gravity. Suddenly, all the material in the star rushes in toward the center. In the wink of an eye, the core collapses to an incredibly dense state – either a neutron star or a black hole.

The upper layers of the star also fall in, but their implosion quickly turns into an explosion as they're met by a violent surge of energy from the freshly compressed core. The outer layers of the star, including most of the star's mass, are launched into space at speeds of 15,000 kilometers per second or more in a stupendous blast called a supernova. Along with hot gas is released an intense burst of radiation, including ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma-rays, that flies outward at the speed of light. The question is what, if any, effects such a blast could have on us, far across space.

At a distance of about 640 light-years, Betelgeuse isn't exactly in our stellar backyard but it's among the nearest stars to the Sun that are doomed to go down the supernova route. Quite when it will explode is anyone's guess. It might already have done so for all we know, given that it takes six centuries for its light to reach us. The best estimate scientists can give is that it will likely blow apart sometime in the next 100,000 years – a mere finger-snap of time by cosmic standards.

When the fateful day does come Betelgeuse will erupt as a so-called Type II supernova. As its outer layers head spaceward at about five percent of the speed of light, its spent core will rapidly shrivel to become, probably, a neutron star some 20 kilometers across. Effectively a solid ball of nuclear matter, a neutron star is so dense that a thimbleful of its contents would outweigh the entire human population.

Seen from Earth, the exploding Betelgeuse will get nearly as bright as the full Moon and be visible for two or three months in broad daylight. But, at our distance, we won't be in any danger because the vast amount of energy released by the supernova will be spread over a bubble of space with a surface area of more than a million square light-years.

Type II supernovae don't pose any threat to planets that are hundreds of light-years away because their initially deadly radiation spreads out equally in all directions and eventually becomes too thin to be of concern. But there are other kinds of stellar denizen that we do need to fear – in some cases, even if they're pretty remote.

Ageing heavyweight stars, such as Betelgeuse, that manage to hold onto an inflated envelope of gases, right up to the last minute, blow up as Type II's. Even heavier stars that, toward the end of their lives, shed most or all of their outer layers leaving behind a massive exposed core, explode as Type Ib or Type Ic supernovae, and some of these can be very dangerous indeed.