beak

The hummingbirds feed on nectar. They have a preference for flowers with tubular heads, inserting their beaks into the opening and lapping the nectar with their tongues. The length of the bills varies with the size of the flowers visited.

Why the toucan's bill should be quite as long is something of a mystery. Certainly the bird's reach is considerably extended. The bill, made of horny skin covering a delicate meshwork of bone, is not so heavy as it looks.

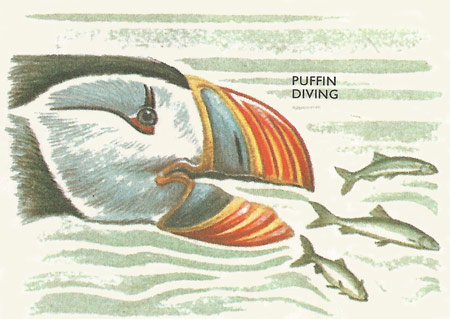

Puffins and their relatives (auks and razorbills) live off fish. The broad bill of the puffin can carry several fish at once. The bird bites deeply into each caught fish preventing its escape.

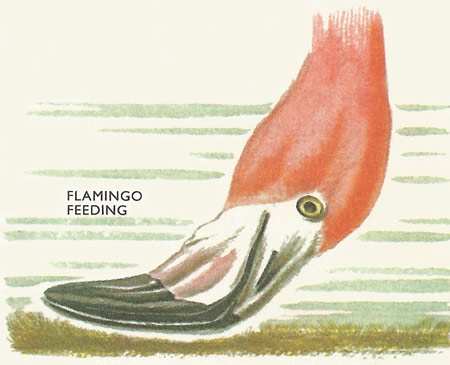

The flamingo is a unique feeder. When the bent beak is immersed in water, the top bill becomes bottom-most. Water is pumped by the lower bill through slits in the upper bill. The tongue filters food out of the water.

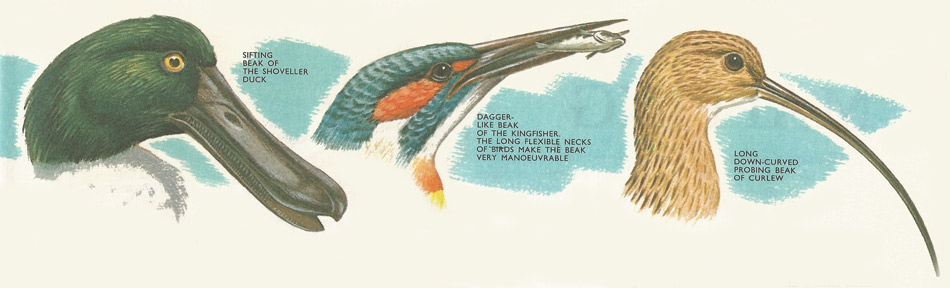

A beak is the general term for a rigid, projecting oral structure. Beak shapes and sizes are usually highly specialized. The buzzard's beak is sharp-edged, hooked and powerful. it is a vicious instrument, ideal for tearing flesh from carcasses. But such a beak is useless for fishing. The heron, on the other hand, with its long, sturdy, tapering bill, is an excellent fisherman. For hours it may stand motionless and then when a fish is sighted the bill stabs rapidly downwards into the water.

The earliest birds, 150 million years ago had no beaks; their jaws were equipped with teeth – just like their reptilian ancestors. But today's birds have lost their teeth and the beak has appeared – a layer of horny, hardened skin covering the upper and lower jaws.

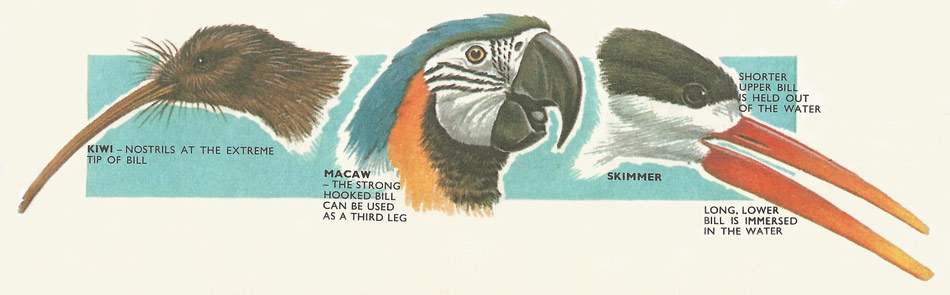

The beak is not a complete substitute for teeth. Though used for biting, tearing or cracking seeds, most mastication of the food takes place internally. But the beak has largely taken the place of the forelimbs. In birds these structures are adapted as wings. They no longer can be used for grasping, clutching, or conveying food to the mouth as in other upright creatures. The beak sometimes, with the help of the feet, must do the necessary probing and plucking and holding; it also must be used for personal cleaning and grooming as well as carrying out such functions as nest-building and feeding the young.

The design of a beak reflects the predominant diet of the bird in question. As the food consumed by birds is so variable – from flesh of other animals to the nectar of flowers – so the variety of beak is correspondingly enormous. Specialized hunting birds have sharp hooked beaks suitable for tearing flesh. The buzzard has already been mentioned. Other flesh-eaters are the eagles, hawks, falcons and owls. Scavenging birds such as vultures may also have hooked beaks; alternatively the beak may be long and stout – crows and the marabou. Birds like the heron, with fish as a staple diet, are equipped with a long, dagger-like beak. Examples are the terns, kingfisher, the guillemots and the gannet. Beneath the long tapering beak of the pelican, loose skin of the throat can be distended into a dip net for receiving fish. The oyster-catcher has a long, blunt, vertically flattened bill well adapted to opening oysters, probing deep in mud or prizing limpets from rocks.

Seed-eating birds such as finches, buntings and siskins have short, thick strong beaks. Hard outer seed cases may have to be cracked; the stout beaks exert great pressure – just like the area near the hinge of a pair of nutcrackers. These beaks are also excellent for nipping off young buds. Another seed eater, the cross-bill, has the upper and lower halves of its beak overlapping. With this device it can pick up the smallest seeds without difficulty.

Blackbirds, thrushes, starlings and many other birds have moderately long beaks. They are not long enough to fish but sufficient for probing for worms, eating molluscs, and grubs, and pecking at soft fruits.

Wading birds that probe for worms and molluscs in soft mud flats have long beaks which are flattened sideways and sometimes curved downwards. The beaks are well provided with nerves at the tips and are very sensitive. Characteristic waders are the sandpipers, greenshanks, redshanks and curlews.

Ducks have broad beaks flattened downwards and deeply grooved inside; they are used for sifting worms and small aquatic animals from mud and water, but will also devour herbage, grain and berries. An extreme example of the sifting type of bill is found in the shovellers. Such birds have large, flattened, spatulate beaks which are provided with bristle-like structures about the edges. These retain edible material as mud is squeezed from the bill. The spoonbills have spatulate tips to their flattened beaks. These birds wade along with the beak half immersed in water snapping up anything edible. Numerous nerve endings are present in the tip making it very sensitive.

Flamingos have a unique feeding mechanism. Their beaks are curved right over so that when immersed in the water, the top bill is bottom-most. The pumping action of the lower bill drives mud and water through slits in the top bill. Small edible creatures – algae, diatoms, worms, larvae crustaceans – are filtered out by tooth-like projections from the tongue.

Avocets are famous for their long strongly upturned bills. They wade along, with jaws open, sweeping the bill from side to side either at the surface of the water or near the bottom. Small invertebrate creatures are eaten and also small fishes and amphibians.

The woodpeckers have long, strong, chisel-like beaks. The beak actually bore into the bark of trees and a long protrusible tongue laps up the exposed insects. Tree-creepers also have long beaks but they are much feebler. They do not attack the bark but only probe into its crevices.

Hummingbirds have a diet of nectar. Their beaks, which often curve downwards, are slender and thin. They vary in length according to the size of the flower visited. The hummingbird hovers motionless over a flower and inserts its beak inside the petals. The tongue, which can be extended beyond the tip of the beak, either has a tubular tip for sucking or is brushy.

Toucans have enormous beaks and the cutting edges are serrated. Their diet consists of succulent fruits. Certainly the length of the beak helps the bird reach out for inaccessible fruit but need it be quite the size it is? One theory is that the beak evolved for eating some fruit or insect that no longer exists. Perhaps they are used in courtship displays or as recognition marks between species.

Contrasting in size are the minute beaks of the swallows, swifts and night jars. These birds catch insects on the wing, flying forwards with their very wide mouths apart. No probing is necessary and the function of the beak is relegated to grooming.

One bird, the woodpecker finch is the Galapagos Archipelago, uses its beak for handling a tool – just as Man uses his hands for controlling a variety of instruments, The 'tool' of this extraordinary finch is a cactus spine; with it, insects are probed from beneath the bark of trees.

Nostrils are usually in the middle or at the base of the beak. But the kiwi that hunts by smell, has them at the tip. Parrots have the upper mandible hinged at the base of the skull; this mechanism provides them with the greatest leverage of all birds. The fish-eating skimmer; the lower, longer bill is submerged in the sea. When a fish is located the upper bill clamps down.

All monotremes, birds (for which the term "bill" is often used), and turtles, as well as some fish. cephalopods, and insects, are beaked, as were many dinosaurs.