heavy element

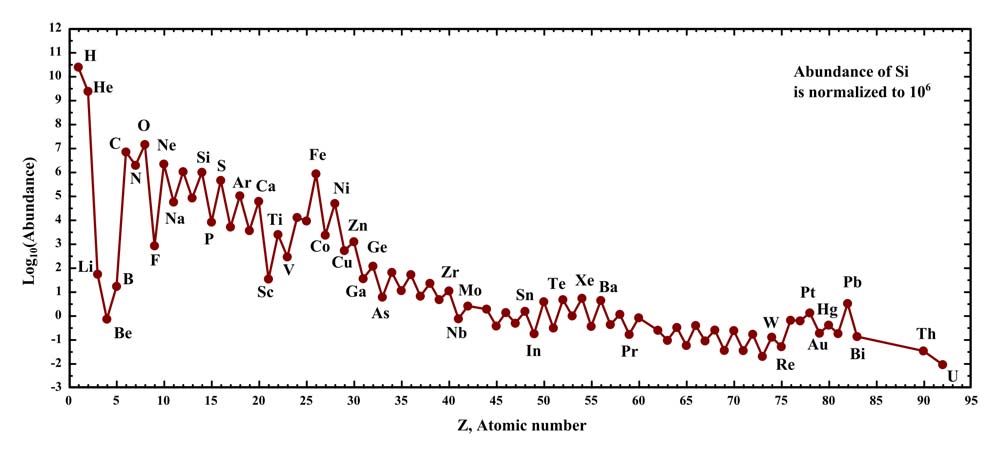

Abundances of the chemical elements in the Solar System. Hydrogen and helium are most common, from the Big Bang. The next three elements (Li, Be, B) are rare because they are poorly synthesized in the Big Bang and also in stars. The two general trends in the remaining stellar-produced elements are: (1) an alternation of abundance in elements as they have even or odd atomic numbers, and (2) a general decrease in abundance, as elements become heavier. The "iron peak" may be seen in the elements near iron as a secondary effect, increasing relative abundances of elements with nuclei most strongly bound.

In astronomical terms, a heavy element is any element heavier than helium. Astronomers also refer to such elements as "metals" (although many, such as carbon, are not). Heavy elements, which are essential for the formation of planetary systems and the evolution of life, are only formed by nucleosynthesis inside stars.

Heavy elements and occurrence of planets

In the absence of heavy elements, it appears impossible that planets or life can form (see planetary systems, formation). But more particularly it has turned out that of the host stars of known exoplanets, the great majority have an above-average heavy element content. Several, indeed, boast the highest known concentration of such elements in our region of the Galaxy, with up to three times the level found in the Sun. This bias has inspired theorists to examine the possible consequences for planet formation and for the frequency with which planets occur in the Galaxy.

Some astronomers have suggested that there may be the equivalent of a habitable zone in the Galaxy, within which stars must lie in order to be able to acquire planetary systems. This narrow band, called the galactic habitable zone and located roughly halfway out in the galactic disk, would harbor material with sufficient heavy element content to enable the condensation of planets in circumstellar disks but not so high as to produce large amounts of debris which would shatter new-formed worlds or lead to planets being thrown around by mutual interactions. Other researchers have argued that there is such a wide variation of heavy element concentration within our own solar system that minor variations in heavy element enrichment elsewhere may not be such an important factor in planet formation. Rather, according to this idea, the high level of these elements in stars known to have planets may be a consequence of one or two planets having fallen into their primaries and consequently enriched the star's surface layers. Stellar ingestion of large numbers of comets and asteroids could have the same effect.