Northern grasslands

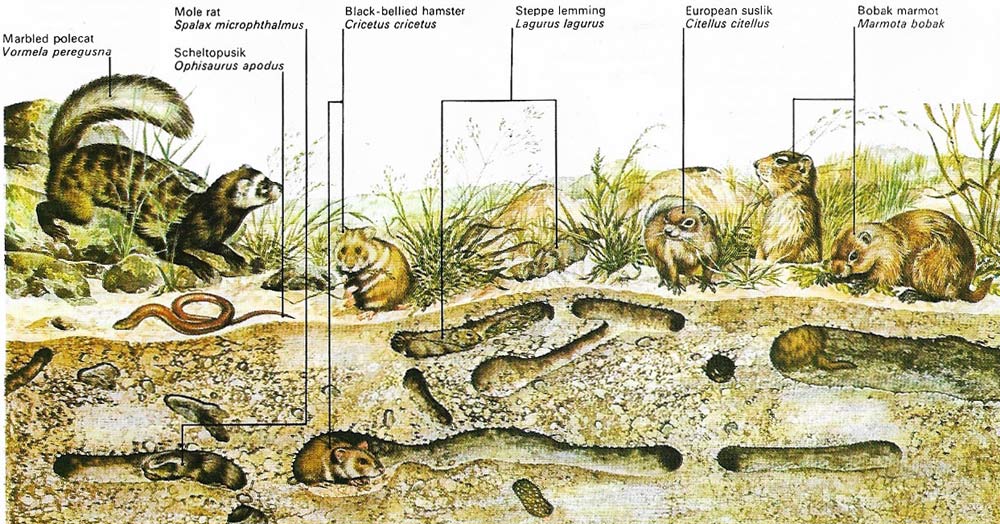

The small animals of the steppes are mostly burrowers. Some, such as the mole rat, feed mainly on plant roots and tubers; others eat the leaves and seeds as well while many species also eat insects. A number of animals hibernate through the harsh winters and some remain underground from August to April. Hawks and owls prey on rodents, and so do small mammals such as the warbled polecat, which often lives in the burrows of its victims. Man, in an effort to protect his crops, is the most implacable foe. Some animals survive his persecution, but the bobak marmot is not one of these and has now disappeared from areas where it was once numerous.

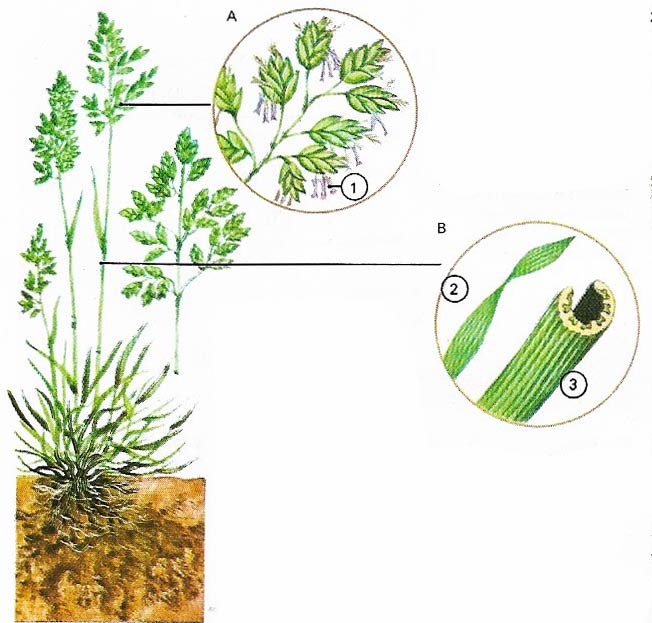

Figure 1. Nearly all grasses are small plants, with a few notable exceptions that grow in the tropics. The typical grass plant consists of a number of shoots, or tillers, made up of a series of tightly rolled or folded leaves and leaf sheaths. Stems are so short that they are invisible until the flower shoot is formed. Grass flowers may be tightly packed. In a spike, or more loosely organized in a panicle (A). Pollen is split from the stamens (1) every time the slightest breeze shakes the flowers. Grass leaves are always narrow with parallel veins (B). In some grasses of arid areas the leaf rolls (2j as water is lost, forming a humid tube (3) to conserve moisture.

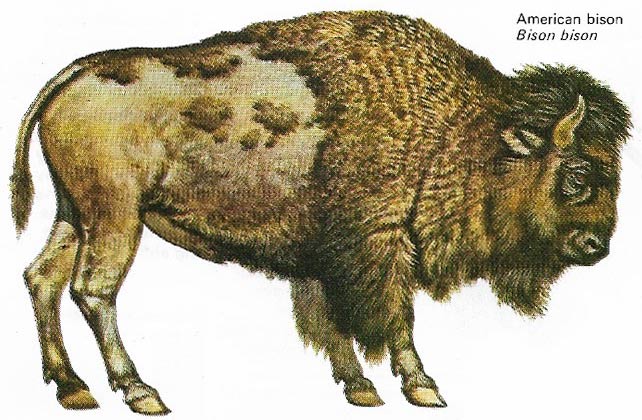

Figure 2. American bison were destroyed partly in order to free land for farming but mainly to deprive the Indians of their wild herds. Strict conservation has ensured the survival of large herds in protected areas.

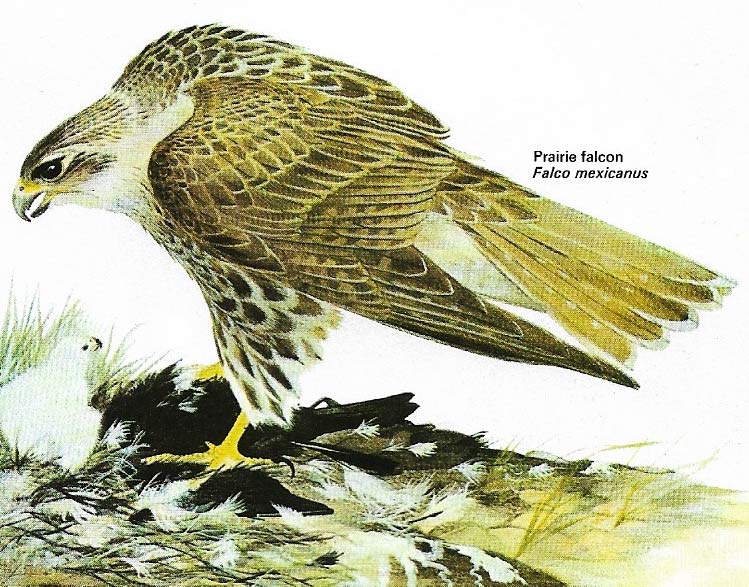

Figure 3. The prairie falcon is a bird of the arid southern and western parts of the prairies. It scans the ground from heights up to 30 meters (100 feet) for small mammals and birds that make up its diet.

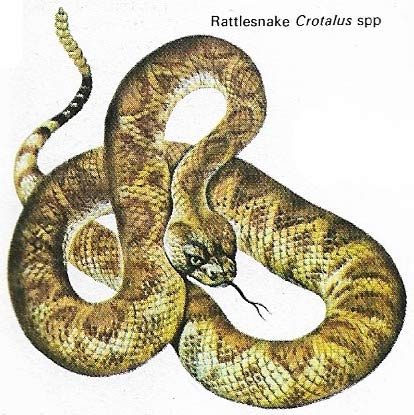

Figure 4. Rattlesnakes are common over much of the grassland and desert regions of North America. The amount of venom they produce far exceeds that needed to kill the rodents that form their usual prey. They use it to protect themselves against large predators, but they are not normally aggressive and try to avoid a confrontation by warning of their presence. Their unmistakable and menacing rattle is produced by "bells" of hard skin on the end of the tail.

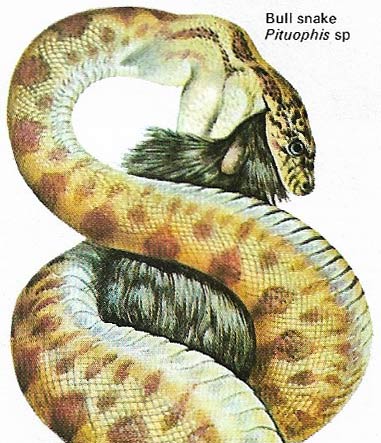

Figure 5. The bull snake, which grows up to 1.2 meters (4 feet) long, is one of the many snakes found in the prairie region, where it preys on the abundant rodents. It is non-poisonous but suffocates its prey with its strong, constricting coils.

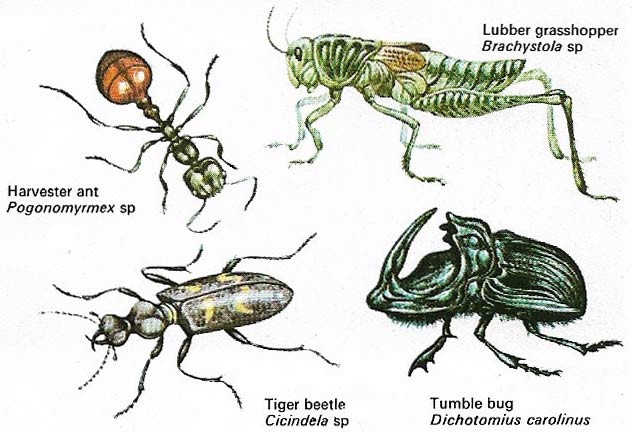

Figure 6. Grassland insects include primary feeders on the herbage, such as grasshoppers, and more general feeders such as ants. Ants are smaller, but the huge colonies in which they live may alter the soil where they burrow. They also often scatter grass seeds, which they gather but do not always use. Predators such as ground beetles abound. The scavenging tumble bug fills a niche by breaking down the dung of other animals and returning it to the soil.

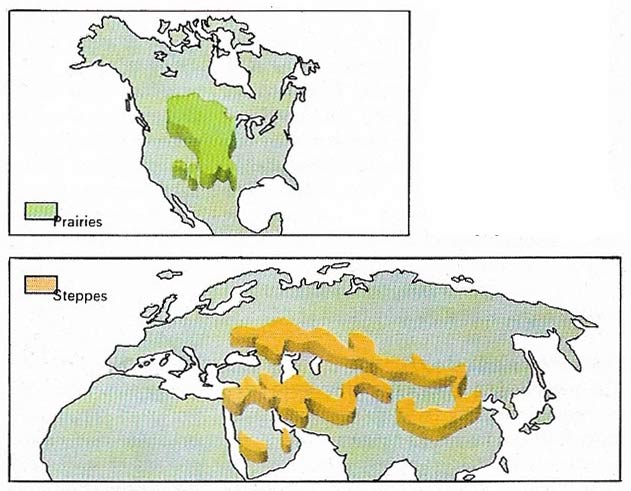

Figure 7. The prairies of North America occupy much of the central part of that continent. They are almost entirely surrounded by forests and only in the southwest do grasslands yield to desert regions in the shadow of the Rockies. In the Old World the natural grasslands or steppes start in eastern Europe and stretch across the Eurasian land mass in a great belt that is bounded o mother south by semi-desert and scrub, and on the north by forests. North of Mongolia the steppe becomes discontinuous as it is broken by trees. But the steppes reasserts itself on the pains of Inner Mongolia and in the northeast of the Soviet Union.

Grasses were among the last families of flowering plants to evolve. They have more than made up for lost time, however, and are now the dominant plants over much of the world. In the Northern Hemisphere grasslands occur in the prairies of North America, the steppes of Europe and central Asia, and in areas extending along the valleys of some of the great rivers of eastern Asia (Figure 7). In general they are found where rainfall is too low to support tree growth, yet above the level at which semi-desert conditions prevail. Paradoxically, grazing animals and fire help to promote the growth of grasses.

Grasses and grass-eaters

Winds sweep unimpeded across the steppes and the prairies and the grasses make use of them for pollinating their flowers. Unlike those of many other plants, grass flowers (Figure 1) are not large, gaudy, sweet-scented or provided with nectar. Instead they possess the bare minimum of stamens with abundant lightweight, non-sticky pollen grains and stigmas to be pollinated by them. During their development the reproductive parts are surrounded by protective scales, which later enfold the seed. The stamens and stigmas are ripe for only a comparatively short time, but the amount of pollen produced is so large that when the plant is shaken by the wind pollination is almost inevitable.

One reason why the grasses are successful lies in their compact with grazing animals. The growing point in grasses lies close to the ground and when the foliage is cropped at a higher level it does little harm because the cut leaves simply continue to grow upwards with little or no interruption in the growth pattern. As a result the grazing animals can feed without damaging their food supply.

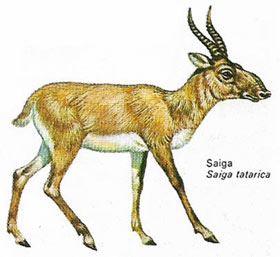

Large grazing animals are abundant in grasslands within the temperate areas. But individuals are relatively few where they were once present in huge numbers. Experts estimate that in 1700, before the coming of the white man to the prairies, more than 60 million bison (Figure 2) wandered over the plains, in addition to large numbers of pronghorn. In Asia, herds of wild horses, asses, saiga antelopes, and camels abounded. In both continents these large animals had been almost eliminated by the end of the last century – in 1899 fewer than 550 plains bison survived. Careful conservation has gone some way to restoring the position, particularly with regard to the saiga and the pronghorn over part of their respective ranges. All these large mammals are herd animals that migrate with their food supply, so the grass is never overgrazed or badly trampled. They were once accompanied by predators, principally wolves, but as the great wild herds were destroyed the predators were also doomed.

|

| The saiga antelope lives on the more arid western Asiatic steppes. Apart from the value of its flesh, hide and fat, the horns were prized as trophies and by the early 1900s few saiga remained. Complete protection was enforced in 1919. By 1930 there were about 1,000 survivors, but today there are so many animals that more than 250,000 are killed annually for their meat and hides. |

A variety of animals

Small mammals were also once abundant on the plains but, unlike the large creatures, they were sedentary (top illustration). Some, such as the prairie dogs and susliks, lived in great colonies that at one time often included several million individuals in a single "township". These animals feed mainly on the grasses, eating the roots as well as the leaves, but often also renewing the plant growth because of their habit of gathering and storing seeds. The burrows of these animals are not very deep, but in digging them they turn the soil over, sometimes bringing up material of a different mineral type from below. As a result, the site of such a colony often displays a different type of soil from that of the surrounding area.

Birds of the grasslands include plant – and seed-eaters that parallel the mammals in their activities. Some, such as the bustards, are large and reluctant to fly, a propensity that has regrettably increased their rate of destruction. There are also many smaller species of birds, which feed both on seeds and insects. They in turn may fall prey to several species of falcons (Figure 3), hawks, and eagles, which patrol the plains.

|

| The stone curlew was once common on grasslands from Britain to Eastern Europe. As a result of its ground-nesting habit and reluctance to fly has disappeared from many of its former haunts. |

|

| The crested lark is common in dry Old World grasslands. |

|

| The burrowing owl, from the grasslands of the US, lives in the disused burrows of prairie rodents. |

Other predators include large numbers of reptiles (Figures 4 and 5), which may feed on eggs or young birds, as well as small mammals whose underground homes they can enter. The insects of the grasslands (Figure 6) are an important part of the fauna and repeat in miniature the pattern of primary herbivores and include hunters and scavengers, which are not well represented among the bigger creatures. Insects and other invertebrates may lack universal appeal, but their importance in the economy of the grasslands can scarcely be overestimated because they stimulate soil fertility an help to hold erosion in check.

The most important of the grassland animals is man, who probably underwent important stages in his evolution in tropical grasslands and who has subsequently spread to other environments. He is, however, still mainly dependent on grasslands for his food – all cereals are cultivated grasses and most of man's domestic animals are species that still need grass for their survival.

The threat to the grasslands

It is ironical that although man has greatly increased the area of the world's grasslands, mainly by the destruction of forests which he has replaced with short-lived farm crops, he has in many areas of the world destroyed the grasslands too by overgrazing and returning too little to the soil. Sometimes, in his attempts to improve productivity with heavy yield farm corps, he has ploughed up the grassland and harmed the delicate balance between plants and animals. This has led all too often to erosion and as a result deserts have encroached in many areas.