snail

Arion vulgaris, also known as the Spanish slug, eating in the garden.

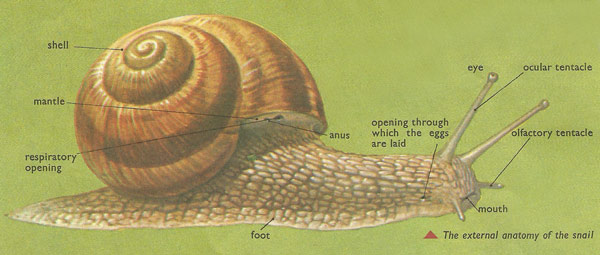

Snail external anatomy.

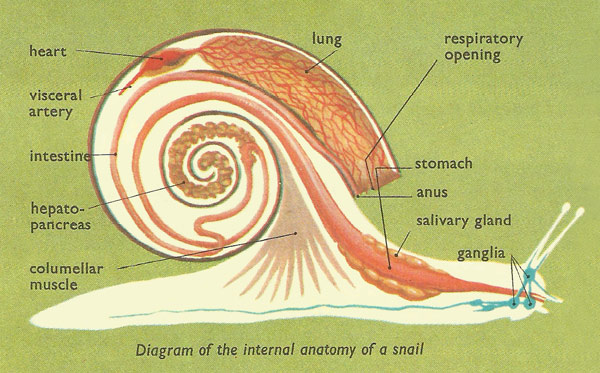

Snail internal anatomy.

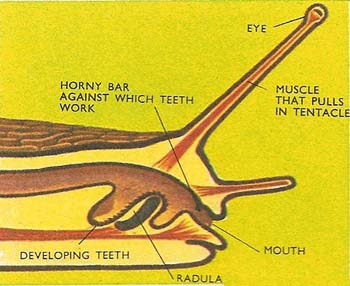

The radula of the snail is a mass of horny teeth that is pushed forward to rasp at its food. The horny teeth are continuously replaced.

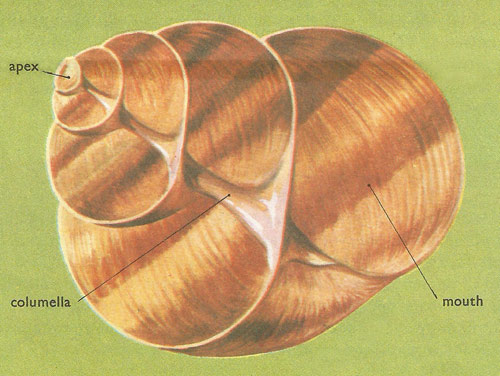

Snail shell.

Giant snail ((Achatina fulica). This large snail is a native of Africa.

A snail is a shelled gastropod (Class Gastropoda), a type of mollusc (Phylum Mollusca), living on land or in fresh water. Apart from a few small groups, snails do not have gills and instead breathe with a type of lung. Because of this snails, along with slugs, are called pulmonates (from the Latin pulmo meaning "lung"). The pulmonates do not have a horny plate to close the shell. Slugs are closely related to snails, differing from them mainly in having no proper shell; a trace of a shell is present under the mantle.

Anatomy

The common garden snail Helix is a typical snail although far from being a typical mollusc. If removed from its shell, the body shows three regions – head, foot, and visceral hump. The hump contains the large digestive gland and some other organs and is spirally coiled. It is covered by a thick layer of tissue called the mantle. Towards the front there is a gap between the body and mantle. This is the mantle cavity. In the marine gastropods this cavity contains the gills. Gills, however, can function only in water and land snails have no gills. The roof of the cavity is very thin walled and well supplied with blood vessels into which oxygen from the air can pass. Carbon dioxide passes out into the cavity.

In marine forms the edges of the mantle are free but in lung-breathers the edges are attached to the body wall except for a small pore. When the snail drops and raises its body wall air is forced in and out of the cavity much as in the mammalian lung. Many water snails can be seen releasing bubbles of gas at the pond surface. They are renewing the air supply in the lung. Some water snails, however, possess a type of gill. A rather strange feature is the opening of the anus and excretory duct into the lung.

Snail shells

Shells vary greatly in shape and size. The shape is largely related to habitat. One interesting variation, however, is the direction of coiling. The majority of snails coil their hump (and therefore their shell) so that, if one looks at the opening of the shell it is on the right of the coil. This is a dextral shell. Sinistral shells are those that have the opening to the left of the coil. The central part of the shell is a hollow rod called the columella but its opening is often covered by the edge of the outer whorl.

The shell is secreted by the mantle and is made up of three layers. A thin, horny layer on the outside covers two layers of calcium carbonate. The innermost layer is very smooth and pearly. The need for plenty of calcium carbonate (lime) explains the comparative rarity of snails on sandy soils, for such soils contain very little lime. Many snails can live only in chalk and limestone regions where there is a high carbonate content in the soil.

Head and foot

The head and foot merge with each other. These are the parts of the body that are outside the shell when the animal is extended. The whole body can, however, be withdrawn into the shell when danger threatens or when conditions are bad. Large muscles attached to the central column of the shell contract and pull the head and foot in. Land snails have two pairs of tentacles on the head. The front, smaller pair are thought to be concerned with the sense of smell while the larger pair carry eyes at the tip. The majority of water snails have only one pair of tentacles and their eyes are at the base of these. Among land snails each tentacle is hollow and contains a long muscle. When this muscle shortens, the tentacles are pulled into the body rather like the fingers of a glove can be pulled in.

Feeding

Snails feed largely on decaying vegetation but, especially in damp weather, they also damage growing plants. The mouth is just under the head and contains a mass of rasping radula. A sheet of tissue is formed inside the mouth and develops numerous horny projections (teeth). The sheet grows continuously and so new teeth continuously replace old ones. This is very important for the snail as the teeth soon get worn down, moving backwards and forwards, rasping away the leaves on which the snail feeds. Some gastropods, for example the whelk, are able to use their radulae to actually bore through other mollusc shells in order to feed on the animals.

Locomotion

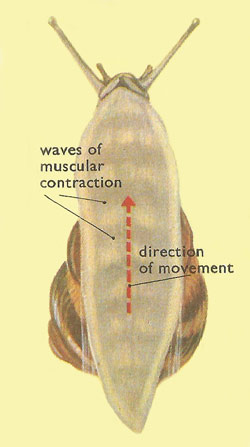

The flat gliding foot of a snail is typical of gastropods. In some marine species it is covered by cilia (tiny hairs) that help in movement but most species move by muscular action. Just under the surface of the foot there is a layer or muscle running lengthwise. Rhythmic contraction of the muscles produces undulating waves on the surface. These waves carry the snail along. They are easily seen in pond snails on the glass wall of an aquarium or if land snails are made to crawl up a piece of glass. The slime trail left by snails and slugs is a deposit of mucus produced by a large gland near the mouth. It lubricates the surface so that the animal can move smoothly over it. The slime also prevents the foot from drying up.

|

Reproduction

Snails are hermaphrodites, which is to say that the organs and functions of both sexes are present in the same individual. Nevertheless, snails need to mate in order to reproduce, because, in most species at any rate, the male and female organs do not become active in one individual at the same time.

After the snail has mated with another of its species it is ready to lay its eggs, which it will do several times in the course of the year. For this purpose it digs a hole in the ground, and drops about a hundred small, white eggs into it. The baby snails that hatch from these resemble their parents, but their shells are thin and transparent and have fewer turns or whorls than those of an adult snail.

Hibernation

In preparation for hibernating a snail closes the mouth of its shell with a sheet of slime mixed with chalk which hardens to form a barrier called the epiphragm. This is slightly permeable to air, so that the animal can breathe just enough to keep alive, but hardly any moisture can escape through it. This is very important, because if a snail's body dried up during its winter sleep it would die.

As soon as the cold of winter gives place to warm, moist weather the snail emerges from hibernation. It secretes a slightly acid slime, which softens the epiphragm, and pushes its way out of its shell. Having slaked its thirst from the rain-soaked grass, it next seeks to satisfy its hunger on young and tender leaves.