GENETIC ENGINEERING: Redrawing the Blueprint of Life - 5. Genetic Information: Ownership and Privacy

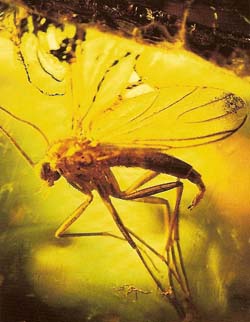

Figure 1. The hands of a person suffering from severe arthritis French laboratory working on mapping the human genome.

Who owns your genes? The answer may seem obvious: you do. But the question of who owns what in the world of genetic engineering is not at all clear-cut.

Companies and laboratories involved in developing new kinds of animals and plants by genetic engineering claim that they should be able to patent these new life-forms. A patent gives a person or organization control over a design and the right to decide who else may use that design.

The first transgenic mammal to be registered by the U.S. Patent Office was a mouse that contained a human cancer-causing gene, known as an ontogeny. Genetically identical copies of the "onco-mouse" were subsequently offered for sale by a big chemical manufacturing company to researchers studying ways in which certain kinds of cancer start in human beings.

The idea of patenting animals and plants is opposed by some people. It is wrong, these critics believe, to treat living things as if they were inventions. On the other hand, supporters of patenting say that it encourages further valuable work in genetic engineering and gene therapy. Patent holders, their supporters point out, can charge other people for using their inventions. The money the patent holders make provides them with funds for additional research and development.

A Revolution in Knowledge

More and more specific genes are being identified as the cause of genetic diseases. Just as important, scientists have also found that the occurrence of certain other conditions, such as cancer and heart disease, may be influenced in part by the type of genes with which a person is born. For example, women who have a particular gene on what is known as chromosome 17 have a much greater chance of developing breast cancer while young than women who do not carry this gene. It is important to remember, though, that cancer-causing substances in the environment, poor diet, smoking, and lack of exercise are usually more significant than faulty genes as the underlying causes of cancer and heart disease.

Genes that make it more likely that a person will eventually suffer from colon cancer, liver cancer, arthritis, Alzheimer's disease, and a number of other quite common illnesses have all recently been found (see Figure 1). Alzheimer's disease is a particularly unpleasant condition. It affects large numbers of people, especially the elderly, and results in a progressive loss of mental and physical powers.

As more becomes known about the genes responsible for various diseases, so the effectiveness of genetic screening as a tool in diagnosis will grow. This is especially true of diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, that are caused by single genes. Screening can be carried out on someone of any age. It can help individuals to know, for instance, whether they carry any faulty genes that could be passed on to their children.

But the increasing effectiveness of genetic screening also raises some difficult issues. As time goes on, employers will look more and more to genetic screening as a way of checking whether future employees will suffer from any genetically linked diseases that could affect their work. The use of genetic screening is seen as a serious threat to people's privacy.

Genes and Privacy

Genetic screening can only be used to predict whether a person might develop a genetic disease. It gives probabilities, not certainties. However, as genetic screening becomes increasingly common, there is the danger that many people will find themselves the victims of discrimination. Suppose, for example, that a screening test shows that a person has the single faulty gene responsible for Huntington's chorea. This disease shows itself first in middle age; the effects usually become noticeable at about age 35 or 40. Thereafter, it leads to a steady breakdown in the sufferer's physical and mental health.

A potential employer who found out that a job applicant carried the gene which causes Huntington's chorea might be reluctant to hire that person. In fact, such situations have already happened. A graduate of a police academy in the Midwest was about to be hired as a police officer when it became known that he had a family history of Huntington's chorea. The man was told he would have to be tested for the gene responsible for the disease before he could be accepted.

Such incidents are likely to be more common in the future as genetic screening becomes widespread. New laws will need to be enacted to protect individuals' rights.

Genetic Disease and Insurance

Health insurance companies also have a great interest in people's genes. Someone suffering from a serious genetic disorder is likely to make large health insurance claims. Because of this, company officials argue that they should have access to genetic information on the people they insure or might insure. But such knowledge could make the insurers refuse to provide coverage to people they think are at high risk for genetic disease.

Already people have either been denied insurance coverage or have received less in insurance payments because they or their dependents have genetic disorders. As genetic screening becomes a more efficient predictor of disease, such discrimination is likely to increase. At present, individuals are not protected by any federal law from insurance companies that discriminate against them because of their genes. Some states, however, including Arizona, Florida, and Wisconsin, have passed laws to protect people against such discrimination.

There is another, equally disturbing danger. The high cost of insuring children who prenatal scanning suggests might develop genetic diseases could lead to more abortions. One insurance company put pressure on parents to abort fetuses with disabilities by threatening to cancel their insurance policies. Some doctors and politicians believe that laws must be introduced to ensure that people have the right to keep information about their genes, and the genes of their offspring, strictly private if they wish to do so.

The Future

It is clear that the new techniques of genetic engineering and gene therapy will solve some important problems while at the same time creating others. Yet, overall, the human race stands to gain much from its increasing knowledge of how to alter the DNA code.

Within 50 years, many of today's most devastating illnesses may not be only treatable but curable. Cystic fibrosis, hemophilia, and other such ailments may disappear entirely. Other diseases that are in part related to faulty genes, such as some types of cancer, heart disease, and Alzheimer's disease may become more easily treatable.

Thanks to genetic engineering, countless new kinds of plants and animals will serve the human race in all sorts of ways. Some varieties of plants will produce plastics and other substances for industrial purposes. Other new strains of plants may be placed on the sides of busy roads to absorb poisonous gases given off by cars and trucks. Plants with altered genes might even help reduce the greenhouse effect by absorbing more carbon dioxide from the air. Meanwhile, transgenic animals will produce valuable medicines in their milk or thrive in places that are highly polluted.

How much human beings will be genetically engineered in the years to come is not at all clear. What is certain is that the choices and laws we as a society make now will have an immense effect on all our futures.

| Bringing Back the Dinosaurs | ||

|---|---|---|

|