Jenner, Edward (1749–1823)

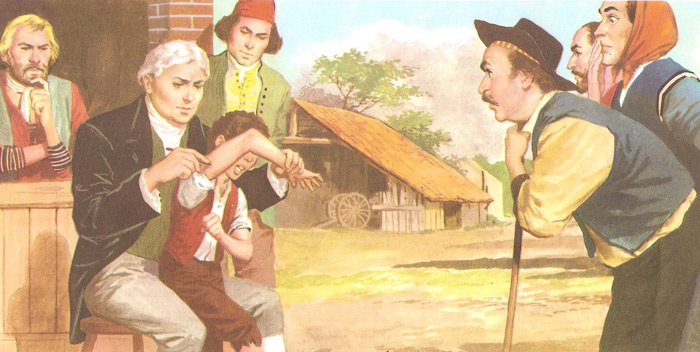

Jenner carries out the first inoculation on an eight-year-old boy.

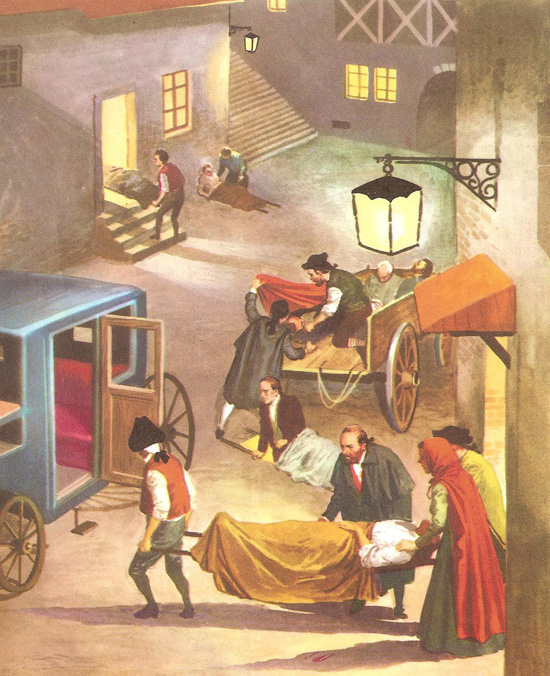

In the dirty streets of old towns diseases spread quickly.

Edward Jenner was an English physician who pioneered the science of immunology. Jenner's inoculation of a boy against smallpox showed the effectiveness of vaccination as a life-saving medical technique.

|

The scourge of smallpox

Until 200 years ago smallpox was the most dreaded disease in Europe, after the plague. At the beginning of the eighteenth century more than half a million people died of smallpox every year in Europe and many more in Asia. In Britain one out of every 13 people in each generation died, and those who survived were disfigured for life by the marks or pocks left by the pustules which appeared all over the face and body during the illness. Other effects of smallpox were blindness and deafness. Smallpox was highly contagious and people could catch it simply by touching any part of the body or even the clothes of a smallpox sufferer.

Early immunizations

In ancient times people had observed that if a person recovered from smallpox, he or she never had it a second time. It made them conclude that if patients could recover, the illness could exist in a mild form. It was therefore advisable to get infected through contact with people who were suffering from the light form, since, as an individual could not get smallpox twice, that person would have a lifetime immunity from it. The first to practice this type of immunization were the Chinese in the 6th century AD. They dressed their children in the clothes of the sick people suffering from a mild form of the disease.

In Europe the usual method of immunization was called inoculation. Doctors would draw off fluid from the pustules of a person suffering from smallpox, dip a needle into it, and then prick their patients. Inoculation was first introduced into England early in the 18th century by Lady Mary Wortly Montagu, the wife of the English ambassador to Turkey. Lady Montagu, whose beauty had been marred by smallpox, saw Turkish doctors inoculating their patients, giving them a mild form of the disease from which they nearly always recovered. She had her six-year-old son inoculated successfully and returned to England full of enthusiasm for the new treatment. But doctors quickly realized that inoculation had its dangers. The illness which resulted from it was not always mild, and was sometimes fatal. For every 300 people inoculated, at least four died, and those who had not been inoculated were continually exposed to infection.

Jenner himself, as a boy of eight, endured six weeks of being bled, purged, and half-starved, the preliminaries to inoculation, and never forgot the experience.

Jenner's breakthrough

Jenner was born in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, the son of the local vicar. At the age of 14, he was apprenticed to a local surgeon and then trained in London. In 1772, he returned to Berkeley and spent most of the rest of his career as a doctor in his native town.

When Jenner was a medical student, he heard a country girl say: "I cannot take smallpox, for I have had cowpox." Jenner told this to his friend and teacher, the great surgeon, John Hunter, who spoke in his lectures of this country tradition that cowpox immunized people against smallpox. In his country practice Jenner discovered, through many inquiries from local farmers, that they often caught a mild form of smallpox from handling their cows. These farmers and farmhands recovered quickly, and the illness left no scars; milkmaids, too, were well-known for their clear complexions and unblemished faces, a rarity among women in those days. Jenner was convinced that cowpox was a modified form of smallpox, and that people infected by it became immune to the more dangerous kind.

Jenner's opportunity to test his theory came on 14 May 1796. A milkmaid, Sarah Nelmes, had infected her hand while milking a cow. Jenner drew off fluid, or lymph, from the blister on the girl's hand, and with this lymph he vaccinated a healthy eight-year-old boy, James Phipps. This was the first vaccination (a name coined by Jenner from the Latin vacca for "cow") ever performed, and it was completely successful: six weeks later, Jenner injected the boy with fluid from a smallpox sore, but the boy remained free of smallpox. Certainly, Jenner's experiment would be regarded as highly unethical and dangerous today, but it proved that the vaccine could give complete protection from this terrible disease.

Jenner gave up his quiet, useful life in the countryside he loved. (He was a naturalist as well as a doctor, and the first to discover, by careful observation, the habits of the young cuckoo.) He submitted a paper to the Royal Society in 1797 describing his experiment but was told that his ideas were too revolutionary and that he needed more proof. Undaunted, Jenner experimented on several other children, including his own 11-month-old son. In 1798 the results were finally published.

Jenner was subjected to plenty of ridicule. Critics, especially the clergy, claimed it was repulsive and ungodly to inoculate someone with material from a diseased animal. A satirical cartoon of 1802 showed people who had been vaccinated sprouting cow's heads. However the obvious advantages of vaccination and the protection it provided won out, and vaccination soon became widespread. From London, where Jenner was honored by the Royal Family, and by statesmen, scholars, and the more enlightened members of the medical profession, the practice of vaccination spread rapidly. Whole towns were vaccinated in East Anglia. A mission was sent by the British government in 1881 to vaccinate the fleet and garrison at Gibraltar and Malta, lately captured by Nelson from the French. In the United States, President Jefferson and his family were vaccinated with vaccine sent by Jenner, and thousands of Americans soon followed.

During the first ten years of the 19th century more than 10,000 people had asked to be vaccinated in London alone. Deaths from smallpox, which had averaged 2,018 annually during the previous fifty years, fell to 622 in that period. The Emperor Napoleon had his son vaccinated and set up 25 clinics for vaccination in the French Empire.

Jenner became famous and now spent much of his time researching and advising on developments in his vaccine. Jenner carried out research in a number of other areas of medicine and was also keen on fossil collecting and horticulture.