Teleostei

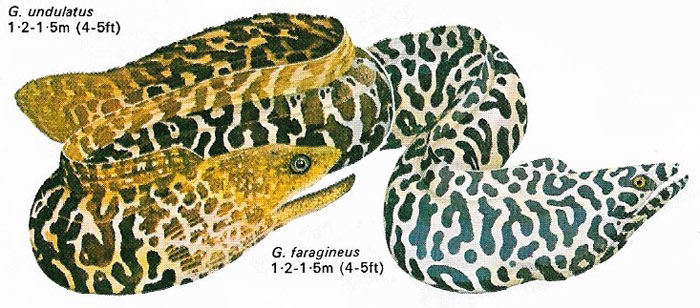

Figure 1. Moray eels, Gymnothorax undulatus and G. favagineus, belong to the super-order Elopomorpha which includes the congers, the largest of the eels. Moray eels are found in all tropical seas and favor rocks and areas of broken ground that provide resting places during the day. They are largely nocturnal in their habits and seldom move during the day except to poke their heads out of their hiding places and snap at passing prey. They can inflict severe bites.

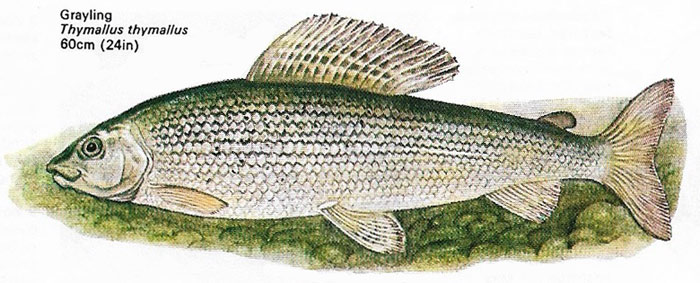

Figure 2. The grayling is a teleost of the Northern Hemisphere and belongs to the salmon group, the super-order Protacanthopterygii. It has an unusally tall and long dorsal fin and its coloring is very variable. During spawning, the dorsal, causal, and anal fins become deep purple in color. The adults are solitary, but juveniles do form shoals. The Latin name comes from the fish's smell.

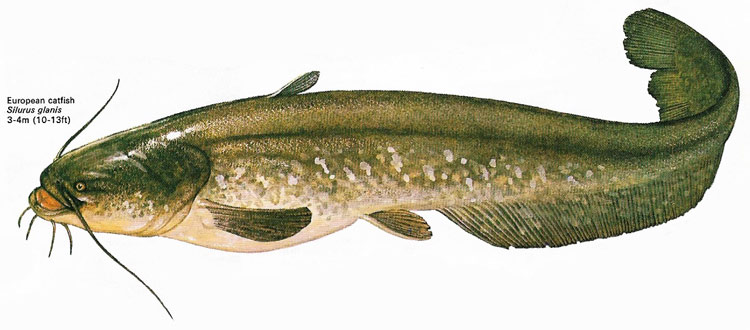

Figure 3. The European catfish belongs to the largest group of freshwater teleosts, the super-order Ostariophysi, which includes the carp and tench. Its common name comes from its barbels which look like whiskers. Catfish are carnivorous and prey on other fish. They may reach 4 meters in length and weigh 200 kilograms (440 pounds).

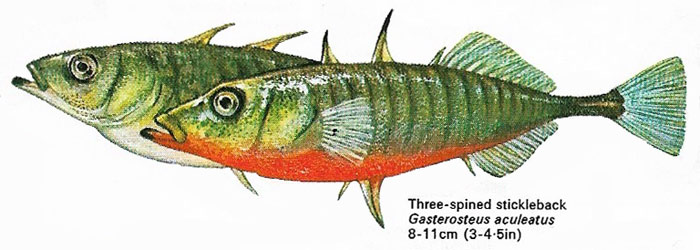

Figure 4. The three-spined stickleback is one of three European stickleback species of the super-order Acanthopterygii. The males build nests and lure females by adopting a bright red belly coloring and performing a complex mating dance.

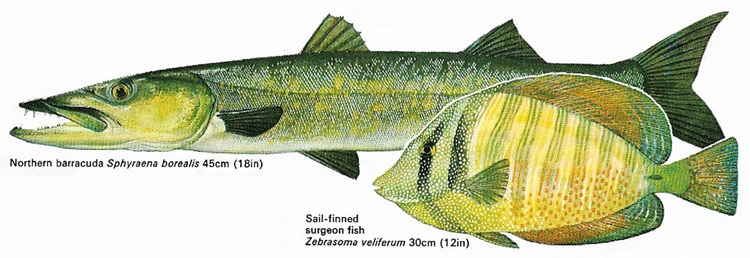

Figure 5. The northern barracuda and a sail-finned surgeon fish appear to have little in common, but both are members of the order Perciformes, the largest order of spiny-finned fish.

The Teleostei is the largest group of living fish, found in both the oceans and in freshwater habitats. The teleosts also comprise the largest group of the ray-finned fish, or Actinopterygii. They are the culmination of the evolutionary line and seem to be perfectly adapted to life in water.

Teleosts are characterized by a fully movable maxilla and premaxilla (which form the biting surface of the upper jaw). The movable upper jaw makes it possible for teleosts to protrude their jaws when opening the mouth. Teleosts are also distinguished by having completely symmetrical tails and with the buoyancy imparted by their swim bladders they do not need rigid paired fins. Many species have developed a streamlined form for maximum speed and minimum friction while swimming, but the locomotion of each teleost is adapted to its mode of life. Thus the flatfish creep along the seabed while the freshwater pike is built for speed and maneuverability.

|

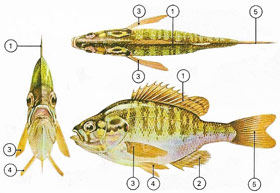

| The fins of bony fish serve as fine controls for movement. The dorsal (1) and anal (2) fins prevent rolling. The pectoral fins (3) often serve as brakes and the pelvic fins (4) control a tendency to pitch upward as the fish slows down. The paired fins also control rising and diving. They are used to produce rolling movements. The caudal (5) or tail fin serves as an extremely efficient rudder. |

Diversity of teleosts

Teleosts have probably evolved along three main lines to give rise to eight super-orders of living fish. The first line includes the eels (Elopomorpha) (Figure 1) and the prolific herring (Clupeomorpha). The second line consists of peculiar tropical freshwater fish (super-order Osteoglossomorpha). The salmon and trout (Protacanthopterygii) (Figure 2) belong to the most primitive group of the third line while most freshwater fish, including carp and roach, belong to a more advanced group, the Ostariophysi (Figure 3). The cod and angler fish (Paracanthopterygii) and strange creatures such as flying fish (Atherinomorpha) are also advanced groups but the final super-order, the Acanthopterygii, whose members are typically fish with spiny fins, is much the largest and most diverse. It includes the stickleback (Figure 4) and the seahorses, the perch, mackerel, flatfish, and puffer fish.