Assyrians 1530 to 612 BC

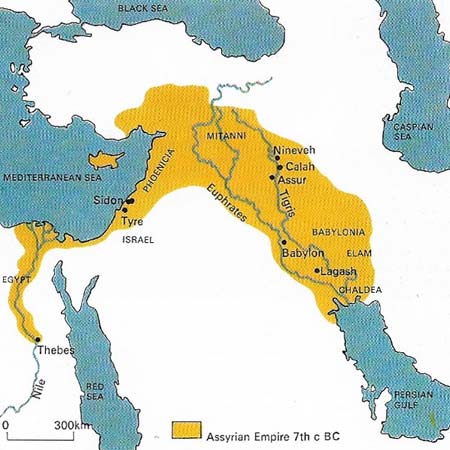

Figure 1. Assyria's empire reached its greatest extent in the seventh century BC, during Ashurbanipal's reign. He subjected its peoples to merciless repression inflicted by his army, in whose ruthlessness he gloried, and ruled through an efficient administrative system supervised by the central government. Assyrian hegemony collapsed, however, and was followed by a brief resurgence of Babylonian rule.

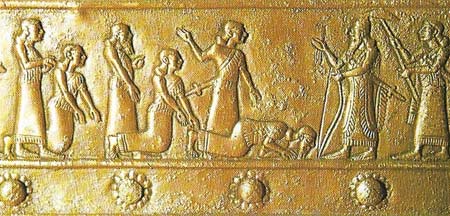

Figure 2. Jehu, the King of Israel, is shown bowing to Shalmaneser III (reigned 858–824 BC) on this panel from the gates of Balwat. The panels record many of Shalmaneser's campaigns – against Babylon, northern Mesopotamia, and Syria, which after several wars he failed to subdue entirely. But he was able to force Tyre and Sidon to pay tribute to him and in 841 BC Israel, too, was forced to become a tributary.

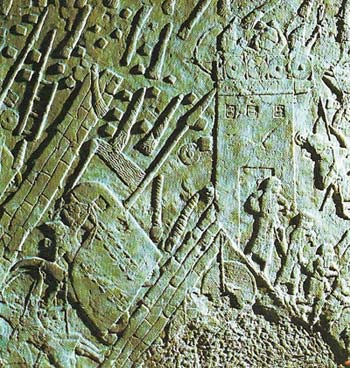

Figure 3. Sennacherib's siege of Lachish, a Judean city, is portrayed on stone panels from Nineveh. The city's fall was followed by the sub-mission of King, Hezekiah of Judah. Many siege machines developed by the Assyrians are represented on stone panels such as the one shown here.

Figure 4. A skin boat on the Tigris carries perhaps building materials for Sennacherib's palace. Herodotus tells how circular hide boats floated down the Euphrates, carrying one or more donkeys in addition to the cargo. On arrival at Babylon, the boats were broken up and loaded on the donkeys for the return journey overland to Armenia.

Figure 5. Two figures, one of 6 them (to judge from clothing and inscription) perhaps representing the 9th-century king Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria, stand on either side of a "tree of life". This motif, common in art throughout Western Asia, is a symbol of fertility conferred by the goddess Ishtar.

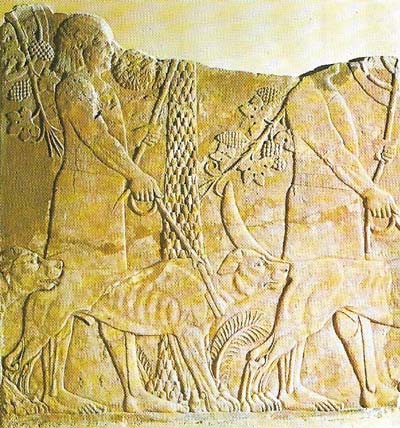

Figure 6. Servants exercise hunting dogs in the royal park in this relief from the north palace of Ashurbanipal II at Nineveh. The Assyrians believed that the king was fulfilling a sacred duty in hunting wild animals, and lions were brought to the country so that the king could show his skill in lavish hunts. Ashurbanipal was a "mighty hunter before the lord"; and in his day the lions that infested thickets along the Euphrates destroyed not only flocks and herds but also human beings.

Figure 7. The valley of the River Zab, in western Iran, a tributary of the Tigris, is typical of the terrain covered by much of the Assyrian Empire. In much of the region mountains ensured that life and communications were centered on the river valleys.

Figure 8. Esarhaddon, the great imperialist Assyrian ruler, is shown on a stele found at Zenjirli, which lies northeast of the Gulf of Iskenderun and northwest of Aleppo. The king towers over two suppliant prisoners, held by cords through their lips. The standing prisoner may be Ba'alu, King of Tyre, although in that case the stele represents Esarhaddon's wishes rather than the facts, for Ba'alurejected his terms and the siege was probably concluded only under his successor. The kneeling figure may represent either Tarku of Kush or his son Ushanakhuru, who was carried off with his family to Assyria; Tarku also retained control of his land.

The Assyrians, a Semitic people in northwestern Mesopotamia, enjoyed a material culture in the mid-third millennium comparable to that of the Sumerians and briefly emerged as a military force under Shamshi-Adad I early in the eighteenth century BC. But for the next four centuries the strongest kingdoms in Mesopotamia were those of the Kassites, who came from the Zagros Mountains to take over Babylonia in the south, and of the Hurrians, who established the state of Mitanni in northwestern Mesopotamia. In the 14th century BC Ashuruballit led the revived Assyrians into Mitanni after that state had been shattered by Hittite invaders.

The empire established

Adadnirari I (reigned 1307–1275 BC) pushed Assyria's frontiers up to the Euphrates, and Shalmaneser I (reigned 1274–1245 BC) advanced northwards and finally crushed the Hurrians. The first of the really great Assyrian monarchs was Tiglath-Pileser I (reigned c. 1115–c. 1077 BC), who came to the throne after a period of instability in western Asia. By a succession of military campaigns, which combined brilliance and brutality, he extended Assyria's authority far into the north and northwest, overrunning Syria and exacting tribute even from the rich trading cities of Phoenicia.

Tiglath-Pileser succeeded, though with difficulty, in keeping back incursions by Aramaean peoples from the western desert. But after his death Aramaean and Chaldaeans overran almost the whole of Mesopotamia, where a kind of Dark Age lasted for more than 150 years. When Adadnirari II came to the Assyrian throne in 912 BC his kingdom was a strip little more than 100 miles long and 50 miles wide. Yet by the middle of the seventh century BC Assyria was the largest and most powerful state in the civilized world.

Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC) (Figure 5) was mainly responsible for the restoration of Assyrian dominion. He built up the army into an irresistible fighting unit and led it to the shores of the Mediterranean. At his new capital at Calah (Nimrud) he built a vast palace, the doorway flanked by winged bulls. The glory of Assyria was paid for by the sufferings of its foes, many inscriptions testifying to the tortures inflicted on soldiers and civilians alike. Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III (reigned 858–824 BC), his father's equal in brutality, continued to conduct annual campaigns (Figure 2), but with less success.

|

| Ashurnasirpal's son Shalmaneser III built this dais for the throne in his palace at Fort Shalmaneser, Nimrud. Its vertical faces show relief carvings of tribute. The upper surface has shallow, round hollows to house the feet of throne and foot-stools, and is covered with inscriptions telling of his reign. |

The surge of imperialism

A series of weak rulers and the growing power of the kingdom of Urartu to the north made Assyria's position a precarious one. The situation demanded a decisive and intelligent personality to meet the threat, and the Assyrians were fortunate to find such a one in Tiglath-Pileser III (reigned 745–727 BC). He reasserted Assyrian authority and established a uniform administration. He transformed conquered lands into provinces, each under its own governor and paying a fixed tribute to the central authority in addition to various taxes and duties. Although the governors had considerable authority, they were supervised by the central government, to which they sent regular reports through a remarkably effective system of posting stages. Tiglath-Pileser initiated a policy of mass deportations of defeated or rebellious peoples. By the end of his reign Urartu was no longer a threat and Babylonia, Palestine, Syria and Phoenicia were completely under Assyrian control.

Babylonia, however, was coming increasingly under the influence of the Chaldaean tribes, which dominated the surrounding country, and which remained bitterly hostile to the Assyrians. Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 BC) reacted with characteristic vigor, installing his son on the Babylonian throne. But in 694 BC the Babylonians revolted and invited the help of the king of Elam, who carried off the Assyrian prince to his own country. The brutal war that followed lasted five years and ended with the leveling of the holy city of Babylon by Sennacherib in 689 BC. He made his capital at Nineveh and initiated a vast program of public works.

Sennacherib was murdered and his son Esarhaddon (reigned 681–669 BC) (Key) at once put in hand the rebuilding of Babylon. He was an able statesman who knew when to temper strength with mercy. Assyrian authority in the east remained supreme and the Mannaen buffer-state in the north was under Assyrian control. A revolt in Phoenicia was settled by deporting the inhabitants of Sidon and executing its king. But Esarhaddon's most spectacular success was against Egypt. The ruling dynasty there had been fomenting trouble in Phoenicia and Esarhaddon decided to subdue the country.

The fall of the empire

Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–c. 627 BC) quelled a rebellion in Egypt and again subdued that country, but as it was too large and too distant an area to occupy permanently (Figure 1) its administration was left to local princes. Eventually, Ashurbanipal was forced to withdraw from Egypt since he was involved in a large-scale rebellion headed by his brother, the King of Babylon, in alliance with Elam. Victorious in 648 BC, Ashurbanipal boasted of having the whole world at his feet. Although ruthless, he was also a man of learning. But Assyria could not survive the alliance of Nabopolassar, king in Babylon in 625 BC, with the Medes. Ashur soon fell and in 612 BC Nineveh was destroyed.

|

| Painted decoration survived in parts of the palaces at Fort Shalmaneser, including the above figure dressed in a fish cloak with scale-covered legs and holding a pine cone in the fertilization gesture common in the reliefs of Ashurnasirpal. |