Roman remains in Britain

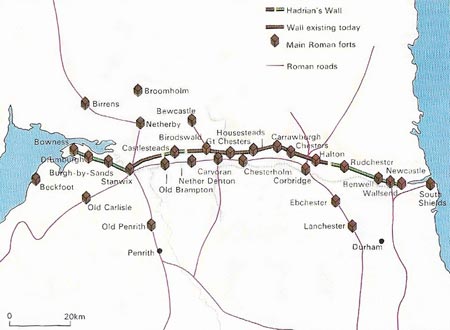

Figure 1. The vast complex of Hadrian's Wall is the largest Roman site in Britain. This map shows the course of the wall, linking the Tyne and the Solway, its many forts and the system of roads and towns that supplied it.

Figure 2. The Fosse Way, in an aerial view near Hinkley, a town in Leicestershire, is typically Roman in its straightness. Roman road builders always took the shortest route between two places, crossing rather than circling hills. Running from Lincoln towards Axminster in Devon, the Fosse Way, built after the first phase of conquest, was one of the earliest and straightest of all the roads constructed by the Romans in Britain.

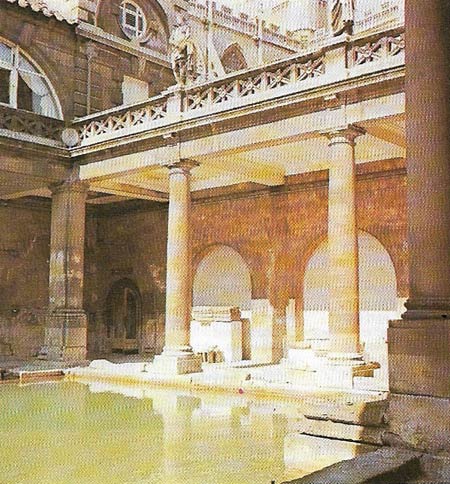

Figure 3. The Great Bath at Aquae Sulis, modern Bath, is surrounded by a modern portico (in the Roman Doric order) but otherwise is substantially as it was in Roman times. The Great Bath is one of three plunge baths created in the 1st century AD, and filled by a natural hot spring with waters at 48.5C (120F) of renowned curative properties. Originally unroofed, it was later covered with a great barrel vault. Roman Bath was an elegant and sophisticated spa town with numerous luxurious villas in the surrounding country. It was visited not only by Britons but also by foreigners. Numbers of inscriptions found there are dedicated to the presiding goddess of healing, Minerva Sulis, from whom the town gained its name.

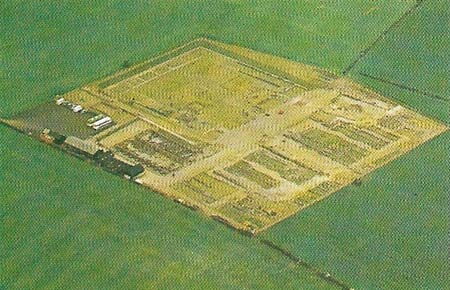

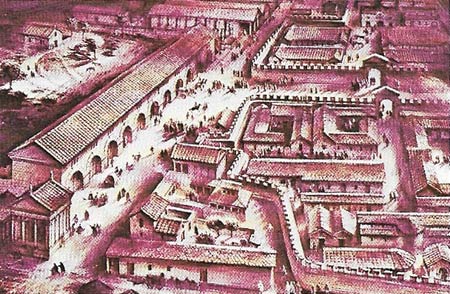

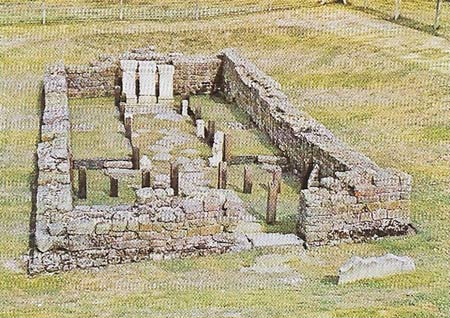

Figure 4. The Roman fort of Corstopitum, standing near Corbridge on the north bank of the river Tyne, is shown as it is now (top), and as it might have been (bottom). The extensive 4th-century remains are typically square in basic plan. The town was both an important fort and supply base, and a wealthy civilian settlement. Its main buildings consist of two large granaries, a general storehouse in a courtyard, several temples and a fountain fed by an aqueduct.

Figure 5. This Mithraeum, or temple to Mithras, the favorite god of the legionaries, is in the fort of Carrawburgh on Hadrian's Wall. At the head of a nave flanked by benches for the worshippers, stood three alters, on one of which Mithras is carved with a halo.

The remains of the Roman occupation of Britain that survive represent only a fragment of the civilization the Romans imported. So much has disappeared largely because the Anglo-Saxons had no use for the towns, roads, fortifications and villas the Romans had constructed, and, abandoning the Roman urban style of living, returned to the land. The remains lay unappreciated until the 18th century, and urban development from the medieval era to the present has all but obliterated many Roman towns.

|

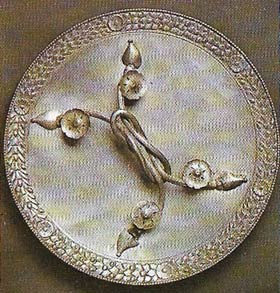

| The most elegant mirror found in ancient Britain, this fine piece of Roman silverwork was once the property of a rich citizen of Viroconium, now Wroxeter. The town was known for its large forum and splendid baths. The mirror is 29 centimeters (11.5 inches) in diameter, and its skilful workmanship perhaps indicates that it was imported from Italy. The handle consists of two thick strands of interlocking silver wire, each of which bears two floral roundels. The mirror is now in Shrewsbury museum.

|

Roman roads and towns

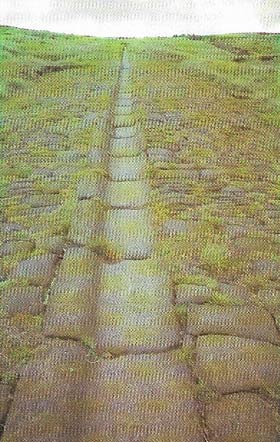

The most universal and unmistakable evidence of their existence left by the Romans is their road system, essential to the swift movement of troops and an efficient administration (Figure 2). Most of the more than 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) of sturdily constructed roads they laid down have been overlaid by modern highways, but are easily identifiable by the straightness of their alignment. The finest stretches of intact road are found in the north, where an embankment (agger) of the road was often metalled with stone paving as, for instance, at Blackstone Edge; in the south less durable gravel, chalk or small stones were used.

|

| At Blackstone Edge above Littleborough in Lancashire there is a long stretch of paved Roman road almost 5 meters (16 feet) wide. It has a shallow trough built of shaped stones that runs down its center. This may have been for drainage, but was more probably filled with turf to provide horses or oxen with a secure footing as they toiled uphill. Beneath the stone paving, so as to provide a firm base, was an embankment (agger) of earth or rubble, with a trench running on either side. This ensured that the road was drained. Not until the 18th century were roads of such a quality to be seen once more in Britain. They were built not for stimulating trade, but for the fast movement of troops and for administrative uses.

|

Not very much remains above ground of the towns that the network of roads was designed to link. In London fragments of the old Roman wall stand isolated, and there is a temple to Mithras similar to that found near Hadrian's Wall. However, quite a good picture of life in the city can be built up from the numerous artefacts found in it. At Silchester in Hampshire the complete circuit of the walls is intact, and the outline of the town's small amphitheatre is visible, as is the amphitheatre at Cirencester. At St Albans the southeasternmost of the four gates has been excavated: it was 30 meters (100 feet) wide, with massive circular towers, and from it a street 12 meters (40 feet) wide led into the city through a triumphal arch. Little of this remains, although there are stretches of wall and tessellated pavements (pavements of small cubical colored stones) and hypocausts (underfloor heating systems) that testify to the wealth and high standard of living of the inhabitants. There is also there a Theatre which became the town's rubbish dump in medieval times.

Something of the former grandeur of provincial capitals can be seen at Bath, York, Lincoln and Caerwent in Gwent; this last was a religious center where a temple and a bathhouse have been excavated. The Multangular Tower at York still rises amid intermittent stretches of wall; at Lincoln traffic still passes through the Newport Arch, formerly part of the great north gate.

Villas in Britain

Roman villas, ranging from enormous village-like settlements to simple farmhouses of five or six rooms, are most common in the milder and more Romanized south, particularly in the southeast, the Cotswolds and Hampshire. Only a few of the more than 500 known or suspected Roman villas in Britain have been properly excavated.

The largest and most splendid of these villas was only recently discovered at Fishbourne near Chichester; it was built in the 1st century AD and contained not only elaborate decoration but the only Roman formal garden to have been found north of the Alps. A villa at Chedworth in Gloucestershire is particularly well preserved; both Chedworth and Fishbourne have museums attached, with a wide range of artefacts used by the inhabitants. Of other examples, Bignor Villa in Sussex is notable for its fine mosaics and the view it offers of Roman Stane Street climbing the Downs; and the villa at Lullingstone in Kent is interesting archaeologically because it is a small but elegant building that has undergone a number of structural altercation.

|

|

|

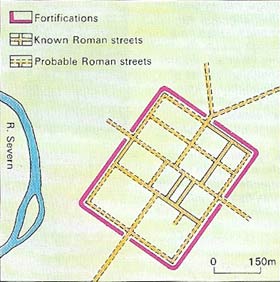

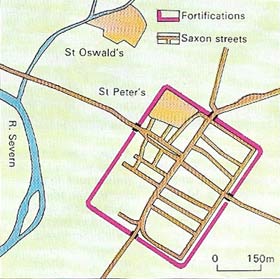

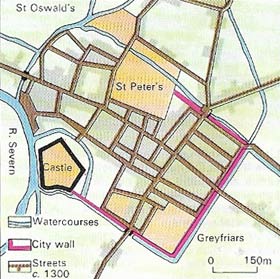

| These tree plans show the development of the Roman city (top) of Gloucester, in late Saxon times (middle), and in the Middle Ages (bottom). Its development, in a pattern recurrent in Britain, reflects its defensible site near a bend in the Severn. Saxon Gloucester contained a shrunken community inside the Roman walls. But a growing population and burgeoning trade in medieval times caused expansion, especially towards the river and to the north.

|

Around Hadrian's Wall

Something of what it cost to maintain and protect the Roman civilization can be seen from the straggling remnants of Hadrian's Wall (Figure 1). The wall itself is 2 meters (6.5 feet) high, and wide enough to walk upon: it has a ditch to the north 2.75 meters (9 feet) deep and 8 meters (27 feet) wide. Along its length are 17 forts of which the best preserved are Chesters, Housesteads, and Greatchesters, but at every Roman mile (1,480 m or 1,620 yd) there was a smaller bastion. A major rampart, 3 meters (10 feet) deep and 6 meters (20 feet) wide at the top, runs parallel to the wall 55 to 75 meters (60 to 82 feet) to the south, and between the wall and the rampart runs a road. The Antonine Wall is also visible in Scotland between the Forth and Clyde.

Numerous fortresses and civilian settlements surround Vindolanda, where a detailed picture of everyday military and civilian life (and the earliest example of writing in Britain) has emerged from excavations. Corstopitum (Corbridge) was once an important supply base (Figure 4)and there is now a museum there with a good collection of Roman-British sculpture, including the "Corbridge Lion". Naturally, most military remains are in the frontier areas, to the north and the west of England, but in the southeast are forts of the Saxon Shore, erected at the end of the 3rd century AD to combat Saxon raiders. Reculver, Richborough, Pevensey, Portchester and, on the east coast, Burgh Castle are the best examples. Lastly, the Roman pharos (lighthouse) at Dover testifies to that port's position as the gateway to and from the heart of the empire.