Scotland 1560 to the Act of Union

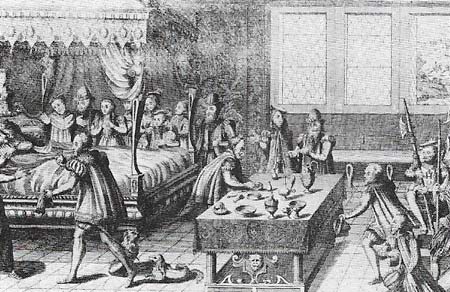

Figure 1. After the death of Henry II of France in 1559 (shown here), the French crown passed to Francis, the husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. This association of the Scottish queen with Catholic France weakened her popularity n Scotland; she adhered to her foreign tastes even after she returned to her home country in 1560. Her marriage to Darnley, also a Catholic, in 1565, was an attempt to overawe the Protestant opposition of Knox and Murray.

Figure 2. Mary’s execution (shown here) took place in England in 1587, on the reluctant orders of her cousin Elizabeth. Mary had been driven out of Scotland in 1568 after the death of her cousin and husband Darnley, who had ordered the murder of Mary’s Italian favorite, David Rizzio, in 1566. Elizabeth imprisoned Mary, who was also the heir to the English throne, for many years to prevent her from endangering Elizabeth’s foreign and religious policies.

Figure 3. The revised prayer book was introduced by Charles I in 1637 and caused widespread disturbances. Much of this was against its imposition on Scottish congregations, but many Scots also regarded the book as a source of dangerous innovations. Popular unrest led to the Covenant of 1638 – a signed agreement to defend the reformed religion. The rebellion of the Covenanters culminated in the First Bishops' War in 1639 which was peacefully settled in the same year. However, the Scottish assembly, organized to resolve the conflict, and the Scottish Parliament openly defied the king. Charles was refused funds for his army by the Short Parliament, and his forces were defeated in the Second Bishops' war in 1640.

Figure 4. General Monck (1608–1670) commanded the English army in Scotland under the Protectorate. He took his army to London and made possible the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, with Charles II as king.

Figure 5. Charles II was crowned by the Marquess of Argyll (1606–1661) (center, right) in 1651, after compromising with the extreme Presbyterian Party. This ended in defeat by Cromwell in 1651.

Figure 6. The Massacre of Glencoe in 1692 took place after the Jacobite rising at Killiecrankie, three years earlier. William III demanded an oath of allegiance from the Highland clans, and the Macdonalds of Glencoe did not take it. As an example to the other clans, 38 of the clan were slaughtered by government troops.

Figure 7. The Act of Union in 1707, was made by commissioners from both countries and then passed into law by the separate parliaments. This process was relatively easy in England, but the Scottish Parliament needed a great deal of persuading by the Duke of Queensberry (1662–1712), shown attending Queen Anne's signing of the treaty.

Figure 8. The English and Scottish Crowns were United in 1603 when James VI was crowned James I of England. But James was not able to effect a parliamentary union of the two kingdoms.

The religious upheavals in Scotland during the first half of the 16th century, initiated by the Reformation, found wide support for political as well as spiritual reasons. The new religious ideas were welcomed by those wishing to loosen the alliance with Catholic France in favor of England, and the nobles, who hoped to gain much from a weakening of the Church's power.

The Reformation and the Crown

With the abolition of papal authority in 1560, Calvinism quickly became the official belief in Scotland, but the ruler, Mary, Queen of Scots (reigned 1542–1567), was a Catholic and a member of the French royal family (Figure 1). On the death of her husband Francis II of France (reigned 1559–1560), Mary returned to Scotland to try to establish her authority as queen.

She proved to be a clever politician but her power and public appeal were always limited by the tremendous influence of John Knox (1505–1572), the leading preacher of the new church. Eventually, in 1567, she was forced to abdicate by the nobility, who were angered at her turbulent marriages (Figure 2). In 1568 she had to take refuge in England, and the nobles put her infant son James VI (reigned 1567–1625) on the Scottish throne with the expectation that a king so created would be their puppet.

|

| John Knox compiled, with other Calvinist ministers, The First Booke of Discipline (1560) which was the blueprint for the creed and constitution of the Protestant Church of Scotland. It decreed a hierarchy of Church courts, substantial stipends for ministers of the new Church, and proposed a generous program of public education. This last had only limited success because the nobility refused to surrender enough of the old Church's wealth to finance it. |

On this point the nobles failed. James grew up to become the most effective ruler of any of the Stewarts. He did this without funds or force, but purely by negotiation and hard work, particularly helped by the fact that he was expected to inherit the English throne. He and his cousin, Elizabeth I of England (reigned 1558–1603), both wanted peace on the Border. In 1603, Elizabeth on her death-bed acknowledged James as her heir. James, known thereafter as James I, moved to England but continued to control Scotland as he said "by my pen" (Figure 8).

James's son Charles I (reigned 1625–1649) could not do this because he did not have the intimate knowledge of the country. His policy of personal rule made the Scottish nobility uneasy for their rights and powers while his religious policy was seen, rightly or wrongly, as contrary to Presbyterian principles. When Charles produced a prayer book for Scotland in 1637 (Figure 3) it provoked the Scots to formulate a claim for their traditional liberties – the National Covenant. Charles's attempts to bring an English army to suppress the Covenanters led to the Long Parliament, and thus contributed to the start of the English Civil War in 1642.

|

| James Graham, Earl of Montrose (1612-1650), was a leader of the Covenanters in the Bishops' Wars. Although later, in the Civil War, he campaigned brilliantly for the king of Scotland. |

The English Parliament persuaded the Scots to join in the first Civil War (1642–1646) by accepting the terms laid down by the Scots in the Solemn League and Covenant, of 1643. But after the war, power lay in the hands of the Parliamentarians' army, which wanted an independent church system with liberty for the individual congregation. Efforts by the Scots to insist on Presbyterianism led to the second Civil War (1648), the execution of Charles (1649) and occupation of Scotland by Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658) (Figure 4).

Stuart restoration and dethronement

When the English Parliament called Charles II (reigned 1660–1685) back to the throne (Figure 5), it was taken for granted that he would rule in Scotland too. However, some of the extreme Presbyterian Whiggamore Party refused to accept any government not chosen by them; this and Charles's policy of re-establishing episcopacy led to disturbances. In this period the Scottish economy became dependent on trade with England. Scotland had to take part in English wars, even when the opponents were The Netherlands (1665–1667,1672–1674), its main trading partner, and economic nationalism in France and Sweden further deprived Scotland of overseas markets.

The Revolution of 1688–1689 against the Catholicizing policy of James II (VII) (reigned 1685–1688) was, like the Restoration, made in England and accepted in Scotland. But there was a larger and more effective resistance group this time, particularly in the Highlands, where many preferred James to the new King William III (reigned 1689–1702) because of William's reliance in Scotland on the unpopular house of Argyll. These Highland Jacobites, or supporters of the Stuart (as the Stewarts became known after 1603) line, defeated William's army in 1689 at the Battle of Killiecrankie in the southern Highlands, but were prevented by a regiment of Covenanters defending Dunkeld from breaking through into the Lowlands. Later, the remaining Jacobite clans were brought to temporary submission by the Glencoe massacre in February 1692 (Figure 6).

Events leading to the Union

With the failure of William III and the next ruler, Anne (reigned 1702–1714), to produce an heir, there was a possibility that the Scottish Parliament might bring back James rather than accept the Hanoverian successor chosen by England. This reasoning seems to have persuaded the English to accept the idea of uniting the parliaments of the two countries. The increasing dependence on trade with England meant that economic sanctions could be used to compel the Scots to accept a union. There was a period of increased interest in the Jacobite cause, and hostility to England in the early 1700s, but in 1707 economic generosity by England and political generosity by Scotland brought about the union of the parliaments in Westminster (9), although leaving the laws and church systems of the countries distinct.