zither

Oki, an Ainu musician from Japan, playing his tonkori.

The harp zither is used by Austrian folk musicians.

The zither has been used as a folk instrument in Scandinavia since the 16th century. In Sweden it is referred to as a langharpa and in Norway it is a langspil.

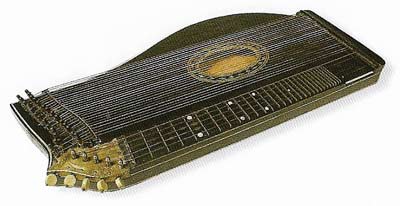

'Zither' is the general name for a large group of instruments, members of which have strings (typically from 29 to 42) that are stretched over a flat, wooden resonating chamber, but don't go beyond it. A zither is placed on a table or on the knees, and the strings are played by the fingers of one hand and with a plectrum on the thumb to bring out the melody more prominently.

Instruments with necks – such as lutes – are not classified harps.

In organological classification the term 'zither' covers a substantial proportion of the world's stringed instruments.

Mouth-bows

A twanged hunting bow can be seen as the common ancestor of all three – zithers, lutes and harps. More developed, the limbindi of the Baka pygmies is a musical bow in which the string is tucked under the player's chin, dividing it into two parts, and then goes back across the bow, making three. It is not loud, but the player can hear through bone conduction and by holding a reflecting palm leaf. Some other bows use the mouth as a variable-volume resonant cavity that can amplify as well as change the timbre. A player of the Ivory Coast dodo puts its tape-like string across his mouth and hits it with a stick. Some other mouth-bows worldwide are played with the wood resting against the side of, or in, the mouth.

Resonators

In parts of Europe, a pig's bladder was once used as a resonator. In Africa the most common resonator is a gourd tied to the bow shaft – for example in Angola's ungo, the progenitor of the Brazilian berimbau or urucungo. Stiffen the bow and more strings can be stretched, as on the Malian orozo. The mvet of Equatorial Guinea has a notched stick attached to the gourd; the strings pass through the notches to make two sounding lengths each.

The bow of the Malawian bangwe is a flat board, along which multiple strings are stretched side by side. The resonator of the multi-stringed Afghan waji or wuj is a box with a skin soundboard, through which the bow-shaft is threaded; in it meet bow, harp and spike-lute. The Malian dan or bambara has multiple bows whose strings pass over the curved side of a hemispherical calabash.

The single string of the Vietnamese dan bau runs from one end of a long rectangular wooden soundbox to near the top of a flexible stick inserted vertically into the other end. The player bends the stick back and forth with his left hand to change the string's tension and thus pitch – in effect like flexing a bow – while with his right hand he picks the string and simultaneously touches it momentarily with the edge of the same hand, producing ringing harmonics.

Stick zithers

Stick zithers are in effect straight bows. They consist of a string-bearing stick with a series of raised sections that function as frets, to which is attached a resonator. The jejy voatavo of Madagascar is typical; it has one set of strings running over the frets, another set running along the side of the stick, and one or two gourd resonators. It is normally played held horizontally in front of the player, very much like the jantar of Rajasthan, which itself resembles early forms of the northern Indian rudra vina or been.

Tube zithers

The term 'tube zither' denotes a category of zithers in which strings run parallel to a tubular soundbox. Often the soundbox is made of bamboo – a material of such tensile strength that it can form the string material too. A one-string tube zither can be made by splitting out a thin strip of bamboo from the tube surface, leaving it attached at both ends, and inserting a bridge-stick at each end to lift the string from the surface.

A raft zither is a series of such one-string bamboo or reed monochords joined together. Examples include the balambala of the Jola people of Gambia and Guinea-Bissau and the Japanese sorghum kokkinna. In the yomkwo of the Birom people of Nigeria, strings are tuned by being bound with thread to increase their mass and thus lower their pitch.

Valiha

The most common form of tube zither is a single tube with multiple strings. The best-known of these is the Madagascan valiha, which can have up to 19 strings around a wide bamboo tube. Most valihas now have steel strings, made from single strands untwisted from bicycle-brake cable. They are tuned, using slideable bridges, to produce a scale by alternately picking on left and right sides of the cylinder with the thumbs and fingers of both hands.

Madagascar was settled by voyagers from Indonesia, where there is a small bamboo-tube zither, the sasandu, which is normally surrounded by a palm leaf to focus the sound. Other valiha-like instruments include the kulibit and saludoy of the Philippines, the jajuka of the Pandonc people of northern Thailand, the kalimantan or Borneo and the koh of the Mnong people of Vietnam, which has tuning pegs and an additional gourd resonator.

The four strings on the paphis-palm-tube zither ngombi na pekah of the Baka pygmies are each divided by a stick-bridge, giving eight notes. Some are struck rather than plucked; an example of this is the celempung of Sunda, Indonesia, which has sound holes that can be opened or closed with the hand to change the resonance. Some are bowed; these include the Laotian saw-bang and North America's tzii'edo'a'tl or "Apache fiddle", a one- or two-stringed bowed zither made from a length of hollow agave stalk. Madagascar's marovany is a transfer of the valiha principle to a box with strings on two opposite sides.

Tonkori

The tonkori of the Ainu people of Hokkaido and Sakhalin is hard to categorize, but can be seen as a non-cylindrical tube zither. It has a long canoe-shaped soundbox, with five strings running the length of it across shared bridges. On some instruments these divide each string into two sounding lengths, terminating in a tuning-peg box. The tonkori had all but disappeared when Ainu roots-rock musician Oki successfully revived it.

Semi-tube zithers

In East Asia there is a large family of long zithers described as 'semi-tube'. In these, the strings pass over a soundboard that is gently curved, like a segment of a cylinder.

The most typical of these – indeed the model for many – is the Chinese zheng or gu-zheng (the latter meaning 'old zheng' and traditionally with 16 strings). Each of the zheng's 21 or more strings passes over its own movable bridge, dividing it into two sections; one is plucked, the other is pressed to bend or vibrato the note.

The koto is the zheng's Japanese descendant, first appearing in the eighth century. Traditionally it has 13 silk or synthetic strings, though some recently developed kotos have more. The Korean kayagum has 12 silk strings. The strings of the Vietnamese dan tranh run to an angled row of wooden tuning pegs set into the soundboard. Closely related to all these are the Mongolian and Tuvan yat-kha, the Khakassian chadagan and Kazakh zhetigen. The Chinese yazheng or yaqin and Korean ajaeng are bowed with a rosined forsythia stick.

Qin

The Chinese qin or chin is a revered instrument that has remained unchanged for over 1,000 years. It has no movable bridges and no soundbox. It is often played on a table to increase resonance. Seven silk strings run from end to end of a long, curved, lacquered board; these are stopped by being pressed to the board.

The Japanese version is called shichigen-qin, meaning 'seven-stringed qin'. The single string of Japan's ichigenkin ('one-stringed qin', and the two of the nigenkin, are stopped with a bone or ivory tubular slide in the manner of a bottleneck in blues guitar-playing. Korea's komungo is unusual among semi-tube zithers in that its soundbox bears a row of wooden frets, on which the central three of its six strings are stopped.

Box zithers

The dominant zither of the Middle East, Turkey and North Africa is the qanun. Trapezoidal with one end rectangular, it has around 26 triple courses of nylon strings that run from a forest of wooden tuning pegs across a bridge that rests on four skin rectangles set into the soundboard. Today's qanums have tangents under the strings to facilitate tuning to microtonal scales.

The zithers of Europe are, like the qanun, generally box zithers which, when unfretted, are sometimes termed 'psalteries'. In Finland, the Baltic states and among some of the peoples of Russia, a family of these instruments are played.

Kantele

The basic form of the Finnish kantele is a small tapering box, traditionally hollowed out of a single piece of wood. It bears five strings, now normally of steel, tuned to the first five notes of a diatonic scale. The strings pass directly – without bridges – from a single metal anchoring bar at the narrow end, to wooden tuning-pegs at the other.

In the 19th century, larger forms of kantele appeared, which had more strings, metal zither pins for tuning, and an individual hitch-pin for each string. In the 1920s the 'concert kantele' was introduced. This has a smooth-levered roller system to make it chromatic. Estonia's kannel, Latvia's kokles and Lithuania's kankles are close relatives of the Finnish small kanteles.

Gusli

The Russian gusli is related too, but has a bridge-strip over which the strings pass before the pegs. The larger guslis developed for Soviet gusli-orchestras have a half-step turn-lever on each string for chromatic playing. The guslis of the Mari and Udmurt peoples are a rounded, truncated triangle in shape, with two curved string-anchoring bars. Despite its cobza-derived neck-like section, the Ukrainian bandura is a zither, too. In Indonesia, the kechapi of Sunda and Bali has evolved into a gusli-like box zither.

Santur

The santur, a widespread box zither, is trapezoidal in form, its strings passing over two or more rows of bridges resting in the soundboard, and played by striking with a pair of sticks. The design probably originated in Persia. Today's Iranian santur has a set of steel strings in quadruple courses, divided by one row of bridges into two lengths sounding a perfect fifth apart. It also has an interpolated set of brass strings, sounding an octave below, running to another bow. Most others have all steel strings. India's santoor has only been accepted as a classical instrument in the past half-century as a result of virtuoso Shivkumar Sharma.

Cimbalom

A cimbalom, tambal, cymbaly, tsimbl or cinbal is a key instrument in musics of many eastern and central European countries. A big table-legged cimbalom with pedals to control string dampers, created in Budapest in the 1870s has been particularly taken up by Roma (Gypsy) musicians and played with astonishing skill and speed. British and American versions are called hammered dulcimer, Austrian and German hackbrett, and in eastern Asia the Chinese yang-chin or yangqin (meaning "foreign zither", and probably introduced from Persia), Mongolian yoochin, Thai and Cambodian khim chin, Korean yanggeum, Vietnamese duong cam and Tibetan gyumang.

Fretted zithers

Another family of box zithers, mainly in north-western Europe, Has some or all of its strings running over frets. Iceland's long, tapering langspil is usually bowed. The Norwegian langeleik is a long rectangular or swell-sided box with one or more strings running over wooden frets, plus some unfretted strings to provide accompaniment and drones.

The Flemish hommel, French epinette, Swedish hummel and Danish humle are similar, but have metal frets, and the usual technique was to fret the melody strings with a short stick. The Hungarian citera, which, now largely fingered (as nowadays is the United States' offspring of these European zithers, the Appalachian dulcimer), has two sets of frets, one diatonic, the other providing the half steps, and drone strings of varying lengths running to a series of separate scrolls.

The Alpine form evolved during the nineteenth century to become the konzerzither, which has five melody strings over a chromatically fretted fingerboard and curving soundboard bearing around 37 accompaniment strings. This instrument was very popular in the early- and mid-twentieth century, its fame greatly increased by zitherist Anton Karas's playing of his theme to the film The Third Man.

Chord zithers

From the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries, a dazzling range of ingenious box zithers was created and manufactured mainly in Germany and in the United States. Sold under a panoply of names, these were intended for home entertainment, and embodied devices to aid the unskilled in picking out a melody.

Autoharp

A type of easily played zither, played with the fingers or a plectrum. Chords are produced by depressing keys.