Burgess Shale

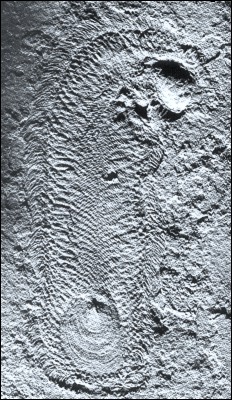

Halkieriid fossil in the Burgess Shale.

The Burgess Shale is one of a handful of exceptional fossil sites worldwide where soft parts – soft-bodied animals and soft tissues – are preserved along with the hard parts. Located in the Canadian Rockies, in Yoho National Park, the Burgess Shale of eastern British Columbia has produced spectacularly well preserved fossils of over 100 organisms, including trilobites, sponges, seaweeds, brachiopods, jellyfish, wormlike creatures, and a number of bizarre life forms that may or may not be related to recognized animal groups.

The dark shales that give the Burgess Shale its name were deposited early in the Cambrian Period, over 500 million years ago, not long after the Cambrian Explosion, the name given to the rapid burst of multicellular life. Because of their exceptional preservation, the Burgess Shale fossils provide precious clues about these early multicellular creatures – from the contents of a worm's gut to the delicate trilobite antennae – information that could never be deduced from hard parts alone.

The fossils also provide clues about the world these creatures inhabited and the events that killed them. The animals of the Burgess Shale lived on and around a vast reef submerged in a warm, shallow sea. (In early Cambrian times, the North American continent was positioned just south of the equator.) At that time, all life was restricted to the world's oceans; the continents were bare and subject to erosion. Now and then, mudslides rolled off the barren continents into the seas, burying the plants and animals living there. At the Burgess Shale site, periodic avalanches of fine mud swept animals from the reef top and buried them, along with any other living thing in its path, at the base of the reef roughly 500 feet below. The fine mud buried the organisms so quickly and completely that the animals died instantly and were entombed in an oxygen-free environment that saved them from destruction by both larger scavengers and bacteria.

The ancient environment of the Burgess Shale furnished two essential ingredients for soft-part preservation: rapid burial in undisturbed sediment and deposition in an oxygen-free environment. Thus, the organisms were saved from immediate destruction and decay. That the fossils somehow withstood 500 million years of heat, pressure, fracturing, and erosion (not to mention the mountain-building forces that brought them to their current position high in the Canadian Rockies), and then were discovered by Charles Walcott of the Smithsonian Institute in 1909 is extraordinary. It is no wonder that in 1981, UNESCO designated the Burgess Shale as a world heritage site.