Cold War, linked to UFO reports

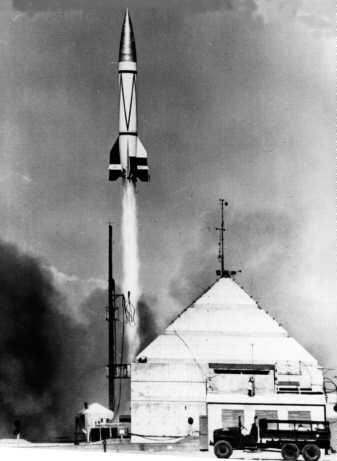

Figure 1. V-2 rocket launch from White Sands, New Mexico.

Figure 2. A scene from It Came From Outer Space.

Anxiety and actual aerial activity related to the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union contributed significantly to the flying saucer flap of the late 1940s. In May 1945, Germany had surrendered; two months later, Japan was A-bombed into submission. Yet despite its military success and new superpower status, America felt more insecure than ever. Already it had been attacked once out of the blue, by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor. Now there was the rising menace of communism and the fear that a Red tidal wave would steadily and relentlessly engulf the free countries of the world. At the end of the War, the United States alone had atomic weapons, but it was only a matter of time before the Soviets, too, would be as lethally equipped.

On 4 March 1947, less than four months before Kenneth Arnold's seminal sighting of a "flying saucer", the Soviets rejected a US plan for atomic energy control. Eight days later, President Truman made clear his policy, the Truman Doctrine, that America should support any country that was trying to resist external threats to its freedom. Rapid military buildup on both sides of the Iron Curtain became a grim inevitability. Although America was strong, it would have to become much stronger and more vigilant. It would have to stockpile weapons, build up its defenses, and use its ingenuity to evolve ever more powerful forms of deterrent, in a desperate attempt to stay one step ahead of the Soviets. And all the time, every minute of every day, it would have to scan the skies, to watch for the moment when the enemy might stir and choose to unleash its weapons on the American homeland.

Nervousness and suspicion, stemming from the communist threat, began to spread among the general public and seep into the national consciousness. But these negative feelings were accompanied, strangely, by a great sense of optimism and confidence about what new technological breakthroughs might bring in other areas. The launch of the first artificial satellite and the dawn of the space age lay only ten years away in 1947. The possibilities of space travel and of finding life on other planets were being discussed widely from a practical standpoint for the first time. And America had suddenly taken a giant leap forward in this direction with the capture of scores of V2 missiles at the end of the War and the decision of the chief German rocket designer, Werner von Braun, to bring his expertise to the US (Fig 1). Those sleek shapes on the launch-pads, it was clear, could be utilized for two very different ends: to reduce enemy cities to rubble or to take the human race on the first few steps of its journey to the stars. Even as the threat of nuclear Armageddon loomed and the Cold War went into deep freeze, people began to feel exhilarated by the prospect of exploring the new frontier of space. It made for a heady brew of conflicting emotions – one that was to boil over in the saucer frenzy of 1947.

Speculation as to what might lie behind the sudden outbreak of mysterious sightings abounded. Were they hoaxes or mistaken identifications of familiar objects? Or was the explanation more sinister: that the skies over America were being visited by foreign devices – from Moscow or Mars? At the start of the saucer scare, the US military appears to have been as confused and nervous as was the public at large. It initiated the first of a series of investigations into the phenomenon, principally to determine if there was a significant threat to national security (see Sign, Project).

In September 1949, the news came that everyone had feared: the Soviet Union had exploded its first atomic bomb. It was time to raise the stakes. The following January, President Truman ordered the development of the hydrogen (fusion) bomb, a terrifying escalation of the arms race. Even as humans contemplated their first sorties to the edge of space, it appeared as if the world was poised on the brink of nuclear catastrophe. On 25 June 1950, Soviet-backed North Korea invaded its southern neighbor. Two days later, Truman ordered American troops to intervene and the Korean War began.

In many science fiction films of the early 'fifties (see Invaders From Mars) the extraterrestrial invaders were a scantily-veiled substitute for the communist threat. And 1950 saw another alien-communist parallel come to the surface. In making his allegation of 57 "card-carrying communists" in the US government, Senator Joseph McCarthy exploited the same fears and anxieties of the American people as the editor of the pulp magazine Amazing Stories, Raymond Palmer, had done several years earlier, with his tales of aliens who abduct unsuspecting citizens, inexplicable memory losses, and mysterious men from the government who were really alien agents. The Men In Black had been joined in the Senate and the Congress by Reds masquerading as true blue patriots. Two years later, the Republicans were in power and the fanatical McCarthy was in charge of the investigation into "un-American activities." If the public had been jittery before, it was driven to the verge of paranoia now thanks to McCarthy's increasingly vociferous and hysterical claims. The Communists, he insisted, were no longer just out there biding their time, mustering their forces; they had managed to infiltrate American society at all levels. No one, it seemed, could be trusted anymore. Neighbors, work-mates, even family members, despite every appearance of innocence, could secretly be operating for the other side. Again, science fiction served both to reflect and magnify a prevalent fear – that the ordinary-looking person standing next to you might not be what they seemed (Figure 2) (also see Invasion of the Body Snatchers). Military interest in flying saucers quickly declined after the initial saucer flap, to be revived temporarily in 1952 following the "Washington Invasion". That same year a much lengthier but low key study of UFOs began under the auspices of Project Blue Book. Meanwhile the Cold War intensified, mistrust by both sides deepened, and the world stared, as never before, down the barrel of a thermonuclear gun.

On 20 August 1953, Moscow announced the explosion of the first Soviet H bomb. Three weeks earlier, the Korean War had ended in stalemate with 30,000 dead American troops. Back home, anti-Communist sentiment had never been higher and McCarthyism was at its peak. With suspicion rife that the Reds had tunneled their way into the very machinery of government and public life, it was not hard for ordinary people to be convinced by conspiracy theories about aliens. Rumors, initiated by the saucer faithful, began to intensify that the government and the military knew more about UFOs than they were prepared to admit. The public was hungry for anything that looked remotely like inside information on the subject of flying saucers, and some fanatics (see Keyhoe, Donald) and charlatans (see Adamski, George), no doubt seeing the commercial possibilities, were happy to oblige – even if it meant peddling fake photos and stories that were manufactured from beginning to end. In addition, there was a subtle shift of public attitude in some quarters toward UFOs in the mid- to late-'fifties, a change of sentiment augured and perhaps partly inspired by the film The Day the Earth Stood Still. What if the aliens were not, after all, malevolent? What if they were actually here to warn us – capitalists and communists alike – of the dangers of meddling with forces over which we had no control? Central to the claim of early saucer contactees, like Adamski, was that the UFO inhabitants were both benign and wiser than ourselves. Far from wanting to take over our planet, they wished to help us, to forewarn us of what might happen unless we could defuse the nuclear time-bomb that had been set ticking. So, although the contactees may have been myth-mongering on a grand scale, they were also reflecting a mood of the times. They voiced what many people badly wanted to believe: first that flying saucers existed, and second that the creatures inside them offered a solution to the most pressing problem facing the world in the 1950s – the very real and imminent possibility of nuclear devastation.