COULD YOU EVER SPEAK CHIMPANZEE? 3. Ape Talk

Figure 1. Young gorillas play while an adult watches.

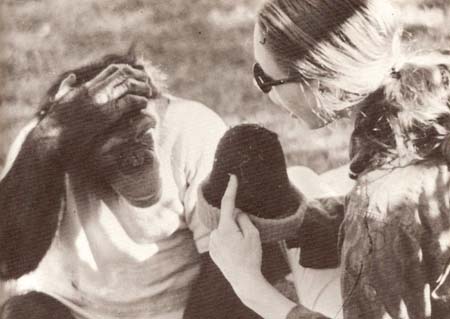

Figure 2. Using American sign language, Washoe makes the sign for hat.

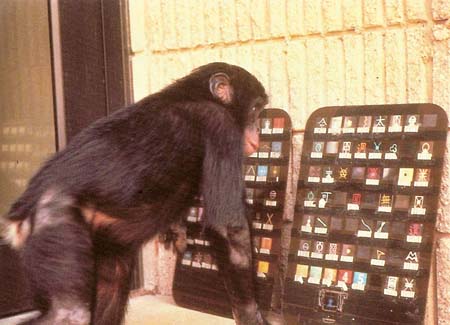

Figure 3. Kanzi examines the symbols displayed on a portable keyboard.

Figure 4. A group of mountain gorillas.

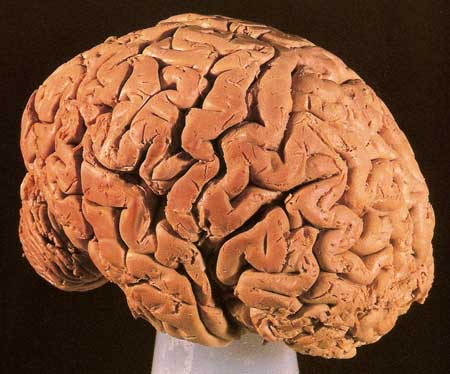

Figure 5. Human brain.

In zoos around the world, one of the most popular attractions is the apes. Chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and gibbons – the four main types of apes – remind us so much of ourselves that we find them fascinating. Of all living species, they are the ones we are most closely related to, both in behavior and form (see Figure 1).

Like us, apes have nimble fingers that can delicately hold and grasp things. Often, apes stand and walk upright. They look after their young with as much care as a human parent.And, like humans, they have large brains and expressive faces.

In the wild, apes are inventive users of tools. Chimpanzees, for example, will often dip a stem of grass into a termite mound to attract the insects inside it, a favorite food. Chimpanzees will also squeeze a leaf "sponge" to get water out of a tight crack. Raised in captivity, apes show off their creative and problem-solving powers in other ways. Chimpanzees will paint lively, colorful paintings like those of a young child, while orangutans are well known to zookeepers as clever escape artists. In some ways, then, apes seem to think and act as humans do.

Apes are great communicators among themselves, too. Researchers such as Dian Fossey (mountain gorillas), Jane Goodall (chimpanzees), and George Schaller have watched and recorded dozens of ways in which these creatures exchange messages. Schaller noticed that, when startled, a gorilla would stand still and shake its head back and forth. Taking this to mean, "It's all right, I intend no harm," Schaller then started making this sign himself whenever he came across a gorilla unexpectedly in the forest. In a simple way, the scientist was communicating with the creature in its own language.

Although apes use a wide range of sounds and facial expressions to communicate with one another, their language seems to be quite basic. They appear to "talk" only about things and events that affect their immediate situation. Like dogs, cats, and other animals, apes send messages about their most important feelings and needs at that moment. Their own language does not seem to deal with ideas that are connected with the past or future.

It is possible that an ape's brain cannot handle more complicated thoughts. On the other hand, the animals may simply lack the necessary communication skills. This is a vital point, For if apes can think about complex ideas, we may be able to teach them enough of our own language for them to be able to carry on a conversation with us.

Signs of Hope

Starting about 70 years ago, several attempts were made to train apes to speak English. Usually, this involved taking a newborn chimpanzee into a household with a newborn baby, and raising both together in the same way. The two youngsters had twin cribs, twin high chairs, and even diaper pails! At the end of three years, the young chimp was far ahead of the human child in its ability to climb, run, and jump. But while the child had already mastered several hundred spoken words, the chimp could only make, with great difficulty, simple sounds such as Mama, Papa, and cup (see Figure 2).

At the time, experiments such as these appeared to show that chimps, and other apes, could not reason or think about language in the way humans do. But later, two scientists from the University of Nevada, Beatrix and Robert Gardner, offered a different explanation for the chimps' failure to learn spoken English. Chimps, gorillas, and other apes, they pointed out, are not physically equipped to make humanlike sounds. They cannot speak like humans because their mouths and vocal chords do not work in the same way. Also, these animals use their voices only when excited.

To find out if apes could learn to communicate in English, the Gardners realized that a completely new approach had to be tried. In fact, there was one way of carrying on a conversation, without speech, that already existed. This method was used by people who had difficulty hearing or talking. It was the American sign language, or Ameslan.

Over the next few years, a number of chimps were given lessons in how to use Ameslan. The language lessons produced some exciting results. Not only did these animals learn how to sign as many as 200 English words, but they even created new words and phrases.

For instance, on seeing a pair of swans in a pond, a young female chimp called Washoe made the signs for water and bird together. In this way, Washoe invented her own label for a swan – waterbird. On another occasion, after she had noticed a small doll lying in her cup of water, Washoe signed Baby in my drink! No one had taught Washoe how to put these words together in that particular order before. It was clear that the young chimp knew how to use sign language in an intelligent and meaningful way.

Once, a reporter for the New York Times, Bryce Rensberger, went to visit Washoe in order to write a story about her. Both of Rensberger's parents could neither speak nor hear. Although Rensberger himself had normal hearing, he had learned Ameslan as a child to be able to communicate with his mother and father. Indeed, he regarded Ameslan as his first language. After spending some time with Washoe, Rensberger made a remarkable discovery. "Suddenly," he reported, "I realized I was conversing with a member of another species in my native tongue."

Conversations With Kanzi

Encouraged by the success of Washoe and other chimps in learning Ameslan, other researchers tried to teach apes different forms of sign language. At the Language Research Center in Atlanta, Georgia, scientists developed a new language called Yerkish. To communicate in Yerkish, an ape pressed keys on a special computer keyboard that was marked with various signs, or symbols. The computer recorded everything the ape "said," even during the night when no humans were present.

By tapping the keys in just the right order, the ape can ask the computer for water, juice, candy, and even music or movies. In this way, researchers found that one chimpanzee, Lana, seemed to prefer jazz music to rock music and movies about chimps to movies about human beings. But the computer could not supply every need. One night, perhaps feeling sorry for herself, Lana punched the keys for "Please, machine, tickle Lana!"

The most remarkable results using the computer at the Language Research Center were obtained with Kanzi, a pygmy chimpanzee (see Figure 3). Pygmy chimps are slightly smaller than the common species of chimpanzee. In fact, some specialists consider them to be the most humanlike of all animals. That belief was supported by Kanzi's language achievements, which went beyond those of any other ape tested up to that time.

"I was astounded when the evidence began to appear that Kanzi was acquiring symbols simultaneously with spoken English," said Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh in 1985. By this, the scientists meant that Kanzi was learning more than how to use the computer keyboard. He was also learning the meaning of words and sentences that were spoken to him. If asked, for instance, "Will you go and get a nappy for your sister Mulika?" he would do it.

Kanzi showed, too, an amazing ability to put words together without training. He identified objects by name and commented on what he was doing. He even described actions that he intended to carry out in the future. This showed that the pygmy chimp could plan ahead and then communicated what he was going to do. It also showed that, while there may be no way to express such thoughts in the animal's own language, Kanzi's brain was able to learn a new language in which such expression is possible.

Though Kanzi rarely made up complete sentences with his keyboard, he did create two- or three-word statements, often without prompting. Once, his fellow chimp, Austin, was moved out of the compound for a time. Kanzi seemed to miss his usual bedtime visit with his friend. But he quickly solved the problem. After several lonely nights, Kanzi types the symbols for Austin and TV on his keyboard. When a videotape of Austin was played, Kanzi settled happily into his nest for the night.

| The Future of Apes

Like many other animal species, all of the great apes – gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans – are in danger of becoming extinct in the wild. They are disappearing because people are still hunting apes, even though this is now banned, and are destroying the forests in which they live. According to one estimate, one acre of the world's tropical forests is cut down or burned every second.

Most endangered of all the apes is the mountain gorilla (see Figure 4). Thanks largely to the efforts of one woman, Dian Fossey, the gentle nature of this magnificent animal, as well as the threats it faces, have become known to the world.

For many years, Dian Fossey studied mountain gorillas in their last remaining stronghold, the Virunga Mountains of Rwanda, Zaire, and Uganda. She set up the Karisoke Research Centre in Rwanda's Parc National des Volcans. Fossey spent day after day sitting in the forest, watching every movement the gorillas made. Eventually, she won the trust of these animals. In fact, they allowed her to live among them and even to groom the great silverback males – the leaders of the gorilla packs.

Tragically, Dian Fossey was murdered by poachers in 1986. Since then, the film Gorillas in the Mist has told to millions of people worldwide the remarkable story of her life and achievements. |

Language and Brains

Language research seems to show that apes do not have a more advanced language of their own because they cannot make the range of sounds that humans can. But if they are taught sign language, they are capable of using words and ideas in a much more complicated way than they do in the wild.

Not all scientists, however, would agree with this. A few researchers maintain that chimps and other apes simply copy what humans do when hey use Ameslan. This is the same, they say, as a parrot that mimics what is said to it without understanding what the words mean. Most scientists, though, believe that the achievements of apes such as Washoe and Kanzi are based on real language ability, not mimicry.

One big difference between apes and most other animals is their relatively large brains (see Figure 5). The heavier a creature's brain is compared with the weight of the rest of its body, the more intelligent it is likely to be. The higher an animal's intelligence, the greater its language skills are likely to be.

Humans have a heavy brain for the weight of their bodies. Even more important, much of the human brain consists of a region called the cortex. In this part of the brain, all types of higher thinking, such as imagination, understanding, and reasoning, are carried out. Parts of the cortex are also responsible for our speech and language abilities.

The brain of a chimpanzee is similar to that of human being. The chimp's brain, too, has a relatively large cortex, although it is only about one-third the size of a person's. The difference in size may explain why a chimp cannot make up or understand long sentences or complex ideas.

It seems, however, that chimps are unexpectedly good at basic math problems. In 1987, Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and two colleagues announced that the chimps they had been studying could quickly pick out which of two pairs of dishes on separate trays contained the most chocolates Chimps may, the scientists concluded, have an ability similar to that of humans to estimate how many objects there are in a group.

Other species of animals also have unusually big brains with large cortexes. In fact, some of these creatures ave brains that are bigger than a chimp's in relation to the size of their bodies. Yet far less is known about them, and their behavior and language, than any ape. These fascinating, intelligent creatures do not live on land where they can easily be studied, but in the world's vast oceans.