COULD YOU EVER SPEAK CHIMPANZEE? 4. Songsters of the Sea

Figure 1. A humpback whale breaches, or leaps above, the ocean's surface.

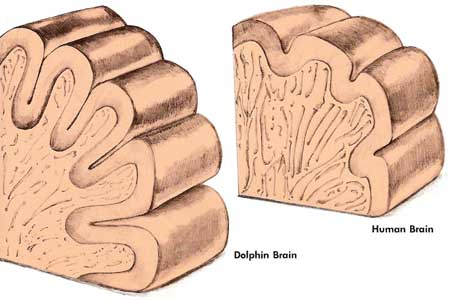

Figure 2. Dolphins have twice as many folds as people do in the front part of the brain.

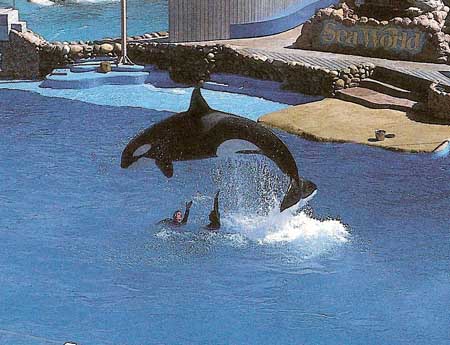

Figure 3. A killer whale performs at Sea World in San Diego, California.

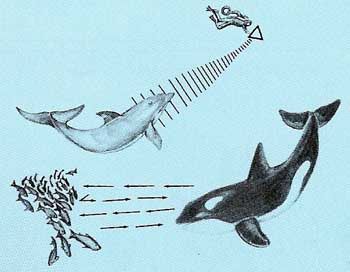

Figure 4. Using echolocation, a dolphin identifies a triangle held by a diver (above); a killer whale locates a school of fish a mile away in two seconds (below).

Figure 5. The fluke of a humpback whale. In the future, scientists may learn more about the mysterious songs of these giants of the sea.

More than two-thirds of the planet's surface is covered by ocean, most of it unexplored. This is the home of cetaceans, a remarkable group of animals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises (see Figure 1).

Cetaceans swim and feed in the water like fish. They have the same sleek shapes and fins as fish. But, like humans, they are warm-blooded, air-breathing mammals. The females do not lay eggs, but give birth to live babies which they feed with milk.

Among the cetaceans are the largest animals ever to have lived on Earth. Biggest of all is the blue whale, a creature so huge that it may weigh as much as elephants and be as long as three school buses, In a day, a blue whale can eat 9,000 pounds of food, and in a single swallow it can gulp down 100 pounds!

One of the most surprising features of cetaceans, though, is the size of their brains. At 20 pounds, the brain of the sperm whale is the heaviest of any animal – six times the weight of the heaviest human brain. Even the familiar bottlenose dolphin, often seen performing at places such as Sea World, has a slightly bigger brain than that of an adult man or woman.

Whale Thoughts

Though some whales have very large brains, this does not mean they are smarter than human beings. As with apes, brain size alone is not an accurate guide to intelligence. What matters more is brain size in relation to body size. Measured in this way, whales are less intelligent than humans because they weigh hundreds of times as much. Much of their brain, according to some scientists, is needed to control their huge bodies.

Yet, it may not be as simple as that. When scientists examined the brains of whales in detail, they found that the brains are especially well developed in those areas normally devoted to higher thought. Whales have unusually large cortexes.

Researchers know that in humans, the front part of the brain is important in the ability to make decisions, to solve problems, and to think about the future of the past. Scientists also believe that the amount of folding on the front part of the brain is related to intelligence. Human brains, for instance, are more folded than chimpanzee brains. These, in turn, are more folded than rabbit brains.

The front part of many whale brains is very large, very folded, and contains a much greater number of brain cells than a human brain does (see Figure 2). It seems unlikely that this region of a whale's brain would have anything to do with controlling the animal's great body. Instead, it is probably used for advanced thinking, just as it is in humans. Still, we do not know for sure.

Whales are difficult to study because they live so differently than humans. They live in the water, while we live on land. Since whales have fins rather than hands, they cannot make or use tools. We have hands with which we can build homes and machines and change the world around us. Whales leave no trace of their activities on their surroundings. To learn more about whale intelligence, we must look at the way they behave and, more importantly, at the way they communicate.

The Mysterious Giants

Millions of people have watched the playful antics and amazing acrobatics of cetaceans in captivity. Dolphins and killer whales are famous for the tricks they perform. Yet, that ability alone does not prove that these creatures are especially intelligent. Properly trained, dogs, horses, and even parrots will perform crowd-pleasing stunts on command (see Figure 3).

To discover how claver cetaceans really are, they must be studied in the ocean in their natural habitat. After all, human beings may seem much less creative if imprisoned than if they are free to do as they like.

To humans, much of whale behavior remains a mystery. But at least some of the things that whales have been observed doing in the wild suggests they are remarkable good thinkers.

Perhaps the most fascinating evidence that whales may be highly intelligent comes from the sounds they make to each other under the sea. Strange, puzzling, and very complicated, these sounds may be part of a language that we are still far from being able to understand.

The Songs of the Humpback Whale

In the mid-1960s, three scientists from Princeton University, Roger and Katherine Payne and Scott McVay, began a study of the weird moans and cries of humpback whales. First, they listened to tapes that had been made a few years earlier using a hydrophone – an underwater microphone – in the seas around Bermuda. Then, they began making their own hydrophone recordings from a small sailboat. What they discovered was totally unexpected.

Each year, during the winter months, humpback whales gather in the same part of the ocean to breed. And each year, at this time, the males make their most beautiful sounds, or "songs." At the beginning of each breeding season, all the humpbacks arrive singing the same song. As the season progresses, though, the song gradually changes. By the end of the season, it can hardly be recognized from what it was at the start. All the whales in a given breeding area continue to sing the same song, and all keep up to date with the current version of the song.

During the summer months, when the humpbacks live alone, they do very little singing. But when the breeding season stars again, they gather once more and sing the same song that they ended with the year before. Then the whole cycle is repeated.

Songs from different groups of humpbacks in different parts of the world show little resemblance to one another. The basic rules, however, seem to be followed for changing them. Some scientists believe that whales are born knowing the rules for composing songs. The whales change the songs according to these rules, and memorize any changes made by nearby singers.

Many animals sing – birds, insects, frogs, bats, and gibbons, to name just a few. But only humpbacks, as far as we know, change their songs from year to year. Why they do this is a complete mystery. The whales may enjoy singing, and their songs may be a way of binding the herd together. Or these huge sea mammals may actually share thoughts and experiences they have had during the year, much as human travelers in olden times shared tales by the fireside.

Based on the evidence known, few scientists would claim that humpbacks are exchanging complex messages. Yet, the ever-changing songs of the humpback remain a mystery.

| The Sound World of the Whale

Though whales can see well, that is not much use in detecting objects over long distances under water, even if the water is clear. It is no use at all below depths of 1,200 feet, where the ocean is pitch black. Fortunately, all whales seem to have the ability to find their way in the water and sight their food through echolocation (see Figure 4).

Not much is known about how whales and dolphins make or hear sounds. It seems clear that their clicking noises come from air spaces inside the head. Air may be forced back and forth very quickly in these spaces to create the clicks. The sounds then move forward through an oil-filled gap in the creature's forehead. Ther they are focused into a more powerful beam, just as a magnifying glass can focus the Sun's rays.

When a whale's click strikes a school of fish, it bounces back. What happens next is not certain. The whale may pick up the returning sound with its jawbone. Finally, the sound travels down an oil-filled channel in the jawbone to the inner ear. From the time it takes the click to travel out and back again, the whale can judge how far away the fish are.

Experiments with dolphins have shown that their ability to use echolocation is highly developed. For example, a blind-folded dolphin can distinguish triangular shapes from circular ones, or a large circle from a small one. Even more amazingly, a dolphin can tell by echolocation alone whether a square object is made of wood, metal, or plastic – from a distance of 100 feet! |

Challenges for the Future

Whales other than humpbacks also fill the ocean with their amazing and beautiful sounds. The blue whale makes what is probably the loudest sound of any animal. These enormous creatures can make themselves heard above the background noise of the ocean for tens or even hundreds of miles. Yet that may not be very far compared to the distances whale calls may one have traveled.

Very large cetaceans, such as the blue whale and its close relative the fin whale, produce sounds that cover an extremely wide range. Some of these sounds are too low for human ears to hear, and others are too high. Today, because of the constant throb of ships' propellers, the ocean is a comparatively noisy place. But until 170 years ago, it was much quieter. Centuries ago, whales were able to each other's cries over a far greater distance. According to some scientists, the deepest moans of creatures such as the blue and the fin whale may have carried through seawater for thousands of miles. If this is true, then any two whales could have heard each other's calls, even if they were on opposite sides of the ocean.

There are many unsolved mysteries surrounding the whales. Perhaps, in years to come, scientists will be able to decode the whales' language so that we can understand what they are communicating to one another. Or we may find that cetaceans think in such a different way from humans that we shall never unlock the secrets of their songs (see Figure 5).

In recent years, scientists have made much progress in communicating with apes. But this has not been achieved by learning the details of how apes send messages to ne another. The apes' own language seems to fall well short of what these creatures are actually capable of expressing. Instead, the real breakthrough in ape-human communication has come by teaching chimpanzees and gorillas to use a version of our own language.

At the Kewalo Basin Marine Mammal Laboratory at the University of Hawaii, Dr. Louis Herman has carried out similar experiments with dolphins. Herman and his staff taught two dolphins, named Phoenix and Akekamai, to respond to about 40 different whistle sounds, These sounds stand for words such as fetch, ball, and frisbee. The dolphins understand short sentences made from these words. What is more, they see, to understand the importance of the order of words in a sentence – an ability that not even apes possess. As research in this field advances, some exciting years may lie ahead in our efforts to share thoughts with other species of life on Earth.