aphasia

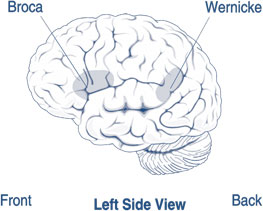

Areas of the brain affected by Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia.

Aphasia is a speech defect resulting from injury to certain areas of the brain and causing inability to use or comprehend words; it may be partial (dysphasia) or total. Common causes are cerebral thrombosis, hemorrhage, and brain tumors.

Aphasia results from damage to regions of the brain, called Broca's area and Wernicke's area, that are responsible for language. For most people, these areas are on the left side (hemisphere) of the brain. Aphasia usually occurs suddenly, often as the result of a stroke or head injury, but it may also develop slowly, as in the case of a brain tumor, an infection, or dementia. The disorder impairs the expression and understanding of language as well as reading and writing. Aphasia may co-occur with speech disorders such as dysarthria or apraxia of speech, which also result from brain damage.

Anyone can acquire aphasia, including children, but most people who have aphasia are middle-aged or older. Men and women are equally affected.

Types of aphasia

There are two broad categories of aphasia: fluent and non-fluent.

Damage to the temporal lobe (the side portion) of the brain may result in a fluent aphasia called Wernicke's aphasia. In most people, the damage occurs in the left temporal lobe, although it can result from damage to the right lobe as well. People with Wernicke's aphasia may speak in long sentences that have no meaning, add unnecessary words, and even create made-up words. For example, someone with Wernicke's aphasia may say, "You know that smoodle pinkered and that I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before." As a result, it is often difficult to follow what the person is trying to say. People with Wernicke's aphasia usually have great difficulty understanding speech, and they are often unaware of their mistakes. These individuals usually have no body weakness because their brain injury is not near the parts of the brain that control movement.

A type of non-fluent aphasia is Broca's aphasia. People with Broca's aphasia have damage to the frontal lobe of the brain. They frequently speak in short phrases that make sense but are produced with great effort. They often omit small words such as "is," "and," and "the." For example, a person with Broca's aphasia may say, "Walk dog," meaning, "I will take the dog for a walk," or "book book two table," for "There are two books on the table." People with Broca's aphasia typically understand the speech of others fairly well. Because of this, they are often aware of their difficulties and can become easily frustrated. People with Broca's aphasia often have right-sided weakness or paralysis of the arm and leg because the frontal lobe is also important for motor movements.

Another type of non-fluent aphasia, global aphasia, results from damage to extensive portions of the language areas of the brain. Individuals with global aphasia have severe communication difficulties and may be extremely limited in their ability to speak or comprehend language.

There are other types of aphasia, each of which results from damage to different language areas in the brain. Some people may have difficulty repeating words and sentences even though they can speak and they understand the meaning of the word or sentence. Others may have difficulty naming objects even though they know what the object is and what it may be used for.

Diagnosis

Aphasia is usually first recognized by the physician who treats the person

for his or her brain injury. Frequently this is a neurologist. The physician

typically performs tests that require the person to follow commands, answer

questions, name objects, and carry on a conversation. If the physician suspects

aphasia, the patient is often referred to a speech-language pathologist,

who performs a comprehensive examination of the person's communication abilities.

The examination includes the person's ability to speak, express ideas, converse

socially, understand language, read, and write, as well as the ability to

swallow and to use alternative and augmentative communication.

Treatment

In some cases, a person will completely recover from aphasia without treatment. This type of spontaneous recovery usually occurs following a type of stroke in which blood flow to the brain is temporarily interrupted but quickly restored, called a transient ischemic attack. In these circumstances, language abilities may return in a few hours or a few days.

For most cases, however, language recovery is not as quick or as complete. While many people with aphasia experience partial spontaneous recovery, in which some language abilities return a few days to a month after the brain injury, some amount of aphasia typically remains. In these instances, speech-language therapy is often helpful. Recovery usually continues over a two-year period. Many health professionals believe that the most effective treatment begins early in the recovery process. Some of the factors that influence the amount of improvement include the cause of the brain damage, the area of the brain that was damaged, the extent of the brain injury, and the age and health of the individual. Additional factors include motivation, handedness, and educational level.

Aphasia therapy aims to improve a person's ability to communicate by helping him or her to use remaining language abilities, restore language abilities as much as possible, compensate for language problems, and learn other methods of communicating. Individual therapy focuses on the specific needs of the person, while group therapy offers the opportunity to use new communication skills in a small-group setting. Stroke clubs, regional support groups formed by people who have had a stroke, are available in most major cities. These clubs also offer the opportunity for people with aphasia to try new communication skills. In addition, stroke clubs can help a person and his or her family adjust to the life changes that accompany stroke and aphasia.

Family involvement is often a crucial component of aphasia treatment so that family members can learn the best way to communicate with their loved one. Family members are encouraged to:

Other treatment approaches involve the use of computers to improve the language abilities of people with aphasia. Studies have shown that computer-assisted therapy can help people with aphasia retrieve certain parts of speech, such as the use of verbs. Computers can also provide an alternative system of communication for people with difficulty expressing language. Lastly, computers can help people who have problems perceiving the difference between phonemes (the sounds from which words are formed) by providing auditory discrimination exercises.

Research

Scientists are attempting to reveal the underlying problems that cause certain symptoms of aphasia. The goal is to understand how injury to a particular part of the brain impairs a person's ability to convey and understand language. The results could be useful in treating various types of aphasia, since the treatment may change depending upon the cause of the language problem.

Other research is attempting to understand the parts of the language process that contribute to sentence comprehension and production and how these parts may break down in aphasia. In this way, it may be possible to pinpoint where the breakdown occurs and help in the development of more focused treatment programs.

Although different languages have many things in common when specific portions of the brain are injured, there are also differences. Scientists are trying to understand the common (or universal) symptoms of aphasia and the language-specific symptoms of the disorder. Other researchers are examining whether people with aphasia may still know their language but have difficulty accessing that knowledge. These studies may help with the development of tests and rehabilitation strategies that focus on specific characteristics of one language or multiple languages.

Researchers are exploring drug therapy as an experimental approach to treating aphasia. Some studies are testing how drugs can be used in combination with speech therapy to improve recovery of various language functions.

Researchers are also looking at how treatment of other cognitive deficits involving attention and memory can improve communication abilities.

To understand recovery processes in the brain, some researchers are using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to better understand the human brain regions involved in speaking and understanding language. This type of research may improve understanding of how these areas reorganize after brain injury. The results could have implications for both the basic understanding of brain function and the diagnosis and treatment of neurological diseases.