philosophy and ethics

Figure 1. A prescriptive law states that some action ought or ought not to be done. Transgression of such a law, for which the woman taken in adultery was condemned to be stoned (A), does not prove that the law itself is invalid. A law of nature, by contrast, claims to be a description of a state of nature and stands or falls by whether it is "transgressed" or not. The stargazer (B) who observes something that confounds a law of nature must record that the law does not, after all, hold true. He is the spectator, speaking a language of non-participatory description, whom Kant, in his examination of practical reason, contrasts with man as active agent. He says that when we abandon the roll of spectator then our language ceases to be neutral and we begin to ascribe values to what we see and to make moral judgments.

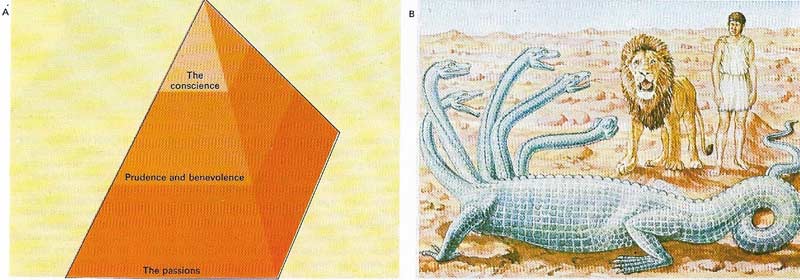

Figure 2. Joseph Butler (1692–1752) appealed to the notion of a self-evidently authoritative hierarchy in the principles of our nature (A). Just as the passions are subordinate to prudence and benevolence, so these in their turn must be subordinate to the rational and reflective control of conscience. By comparison Plato's Republic represents the Man Reason (B), controlling with assistance from the Lion of Self-assertion the Many-headed Monster of Passion.

Figure 3. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), seen with his mother, radically broke with the established conception of ancient Greek culture in his first book The Birth of Tragedy. Thus Spake Zarathustra, his most famous work, argues that the "will to power" is the primary human drive. Anti-Christian polemics become progressively more central in his later books, in which critics discern signs of the madness that overtook him.

Figure 4. Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) was the first major philosopher born in North America. Just as Aquinas had seen his mission as the incorporation of the best of ancient Greek philosophy into a new Catholic synthesis, so Edwards labored to incorporate Newton and Locke into a revived Calvinism. In philosophical psychology his Religious Affections anticipated much of William James's Varieties of Religious Experience.

Figure 5. Confucius (551–479 BC) was born within modern Shantung. His ideas became the greatest single force shaping traditional Chinese civilization. However, his thought was not in our sense philosophical. When, for example, Tzu Kung asked him whether the True Way could be epitomized in a word, Confucius replied: "Is not reciprocity the word? Do not to others what you do not want them to do unto you." But he never made an attempt to show, as centuries later Kant was to try to show, that this is an essential element distinguishing some categorical imperatives as moral.

Philosophical ethics is concerned with how men should behave and involves moral discourse about such concepts as good, right, duty, responsibility, and punishment.

The concepts of good and right

There are many definitions of what constitutes "good". Naturalists identify the concept of good with the concept of some natural, psychological feature. Hedonists say this feature is pleasure, others that it is the object of desire and still others that it is the satisfaction of a need. Non-naturalists dispute these definitions. Plato (c. 427–347 BC) pointed out that there are morally bad pleasures and that if pleasures and good were identical we would then have the self-contradictory notion of a bad good.

In discussing "right" some philosophers assert that the concept of good is more fundamental than the concept of right. In other words, to say of an act that it is right is to say that it is productive of a greater balance of good over evil than any other act open to the agent. Typical of those philosophers who hold this view are the Utilitarians, such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.

|

| John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was intellectual leader of the Philosophical Radicals. Active in all liberal causes, he produced standard works on economics and on logic and scientific method, as well as the libertarian classic On Liberty. Also, following Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), he argued for ethical utilitarianism – a system of morality governed by the idea of the "greatest happiness of the greatest number". |

Opposed to this view' are those who say that right cannot be defined in terms of good. Otherwise it would be possible to judge the intimidation of an innocent person, with the aim of deterring crime, as right because it produced a balance of good over evil.

The characteristics of moral discourse

To be genuinely moral, discourse must have several characteristics. First, it is prescriptive as opposed to descriptive (Figure 1). That is, it contains statements about what ought to be rather than what is. From the confusion of these two comes the naturalistic fallacy of invalidly deducing an "ought" statement from an "is" statement. One popular form of this fallacy is the move from saying that something is natural (in the sense that it happens or tends to happen) to the conclusion that anything else would be unnatural and wrong – not in the sense that it will not happen, but that it ought not to happen.

This seems obvious once clearly stated. But it is quite another thing to see all the implications of this ought/is dichotomy. Obviousness is essentially relative to time, place and person. It was not obvious to Aquinas (c. 1225–1274) when, if only temporarily, he overlooked the crucial difference between those Laws of God that are the scientists' laws of nature and cannot be "disobeyed", and those Laws of God that are prescriptive laws that rule human conduct but are notoriously ignored or breached.

Not all prescriptive utterance is moral. Immanuel Kant distinguishes the hypothetical from the categorical imperative. The former may suggest a course of action in certain cases but is never absolutely categorical, in contrast to a moral imperative such as "Thou shalt not kill".

|

| Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) lived in the East Prussian ' city of Konigsberg, (Kaliningrad). He was raised in the traditions of Leibnizian rationalism, and his own distinctive "critical philosophy" was a response to the challenge of Hume's radically skeptical empiricism. Kant's three main works (Critique of Pure Reason, Critique of Practical Reason and Critique of Judgment) set out to find the nature and limitations of our learning capacities. Kant emphasized the contribution of the knower to knowledge, whereas Locke and Hume had been inclined to speak of materials from the external world impressing themselves upon an originally blank and inert mind. |

Kant further suggested that there are two other conditions that distinguish the authentically moral. The first of these two conditions is universality. If anything is to count, not necessarily as a correct moral principle but as genuinely moral, then it has to be a principle applied universally and impartially. If you claim that the use of chemical weapons or torture is immoral, then this claim must be universally applied; to protest against offences by those regimes to which you are politically opposed, while remaining silent about those regimes which you favor politically, is not to voice an authentic and sincere moral protest.

Kant characterizes the second of his two formal conditions for rating discourse as moral rather awkwardly. He maintains that moral discourse has to be autonomous as opposed to heteronomous. The idea is that each of us must somehow impose his own moral principles on himself, in contrast to the laws of the land which are imposed on us from without. (However, it is often rightly remarked that all such legislation is also in principle subject to the moral assessment of the individual: "I know that this is the law, but is it right, ought it to be the law?").

The problem of subjectivism

The problem is to retain this notion of autonomy without succumbing to some form of subjectivism. In the strictest sense, a moral subjectivist holds that moral words do no more than express the reactions of the person who is using them. But the social "subjectivist" may also, by extension, be one who defines moral words in terms of the class or tribe to which the speaker belongs.

Clearly, any moral argument between two strict subjectivists is impracticable, just as it is between two people, one of whom says "I like chocolate" whereas the other says "I don't like chocolate". The social subjectivist, can at least argue that a group dispute may be settled by a simple vote. Both the subjectivist and the objectivist see the ought/is problem as fallacious, since one believes that morality is based on personal opinion, and the other, in contrast, believes that morality can be determined by the facts alone.

These conflicting approaches, if rigidly held, would make effective moral argument impossible. Any universal moral principle, however, unless susceptible of modification by the proposer, will have consequences unforeseen by him and it is this fact that makes moral argument possible. One of the major purposes of a critical moral discussion is to expose such unacceptable consequences and thus persuade the proposer to amend or abandon the offending principle.

|

| Mencius (372–289 BC) was both in his life and thought extraordinarily similar to Confucius. Born in the same province, both lived as professional moral teachers. Both shared concerns for filial piety and for established rites and both respected the Sage Kings. Both agreed that "Once the ruler is rectified, the whole kingdom will be at peace", a statement from the Book of Mencius. However, it was Mencius alone who made explicit and defended his conviction that human nature is essentially good. Apart from his philosophical teaching, Mencius urged many practical reforms. |